Cross-posted from No Mean City, Alex’s personal blog on architecture

![]()

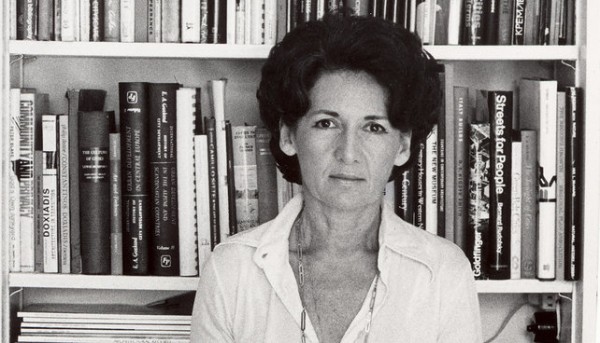

I was deeply saddened to learn this week that Ada Louise Huxtable had passed away. For those of us who write about buildings, she was a titan: a historical figure who basically invented the profession of architecture critic 50 years ago, and was still doing it, very well, this winter.

Nothing I’ve written on No Mean City would be possible without her. Nothing in Spacing would be possible without her.

Here is the New York Times’s obit. It was at the Times that she – “a young, brash, believing woman” with an architectural-history degree – became an unlikely power player in the world of development and planning.

She defined how to write about these subjects for a general audience, bridging the scholarly and the concrete, highbrow and slangy. She understood construction and finance, zoning and traffic, the history of architecture and the realities of marketing. She made architecture part of serious conversation.

She knew that buildings are made out of money, power and politics, and she was also a staunch defender of the public good: grand public buildings, diverse and lively streets, parks that are pleasant to be in, private spaces that serve their users comfortably. Her contemporary Jane Jacobs thought about the big picture; she thought about the big picture and also the details. In retrospect, she was right about everything.

Huxtable had excellent timing: starting in 1961 in New York, she had a prime seat to witness the great excesses of modernist “urban renewal” (including the World Trade Center) and to watch cities figure out how to reinvent themselves for the post-industrial age. In various gigs she kept at it for 50 years.

She was there to witness new York’s old Penn station wrecked, its marble details dumped in the New Jersey Meadowlands. “Tossed into the Secaucus graveyard are about twenty-five centuries of classical culture and the standards of style, elegance and grandeur that it gave to the the dreams and constructions of Western man. That turns the Jersey wasteland into a pretty classy dump.”

This event is widely credited with birthing the modern historic preservation movement, thanks in part to her advocacy. And she immediately saw the new Penn Station, one of the biggest, busiest and ugliest transit hubs in the world, as a disaster. (“The style is not Roman Imperial, but Investment Modern.”) She also understood the real estate economics that made the original vulnerable and the replacement inevitable.

So, you may ask: who cares? That era is history. And Toronto is not New York.

But history repeats. And Toronto, which is not New York, is today a thriving, chaotic, churning metropolis, with creaky infrastructure, a muddled political leadership, brilliant and civic-minded developers, dim and greedy developers, brilliant unemployed architects, shameless hacks, innovative designs, pointless throwbacks, endless mediocrity, moments of genius. Which is which?

We have built literally thousands of large buildings over the past 15 years; many of those buildings will outlive me. Yet there has been very little informed criticism of the architecture, engineering, planning, and urban design that have gone into them.

Toronto needs the an Ada Louise Huxtable provided: a voice to explain and assess what is going on, carefully, knowledgeably, without jargon, with historical perspective, high standards and the heft of an institution. Newspapers in Los Angeles and Philadelphia have them, and New York too.

We don’t have one. In my paper, The Globe and Mail, Lisa Rochon covers all of Canadian architecture and the world with two columns a month. In The Star, Christopher Hume is often writing about governance and politics, while in the paper a student can write incoherently on the architecture beat.

Here, I try to do my part to explain what matters and whether it works. So do some esteemed colleagues.

Mrs. Huxtable showed us all both how and why to do it.

“I wrote from a sense of entitlement, in the belief that everyone deserves, and has a right to, standards of quality, humanity and even art, because art elevates the experience and pleasure of the places where we live and work,” she wrote in 2009.

She found art in the streets, she defended it, and out of journalism she made an art that matters.

3 comments

Well said, Alex.

And even the Chicken Fat Perambulation is offering (with the inevitable doubts to its worthiness) an “Ada Louise Huxtable Memorial Edition”… http://www.facebook.com/events/511033165598052/?ref=22

I have to agree with this article. It’s especially true in the case of Toronto, sometimes I wonder about its architectural marvels. And I must admit I was hardly surprised by the composition of this list.

A well thought concept’s very much needed here I think.