With the city’s casino consultation wrapping up this week and the April council debate growing closer, some of the gaming industry’s key executives have rolled into town to step up the pressure with pot sweeteners and other promises.

MGM Resorts CEO Jim Murren last week pledged during a speech to include a permanent Cirque du Soleil venue and a Mark McEwan restaurant at a casino-resort for the CNE/Ontario Place grounds. And in a speech Monday, Sands president Michael Leven sought to downplay the presence of a casino on the Metro Toronto Convention Centre site, claiming it will represent only 5% of the floor space and generate just 30% of the revenues for the overall development.

In case those promises aren’t sufficient, the University of Nevada Las Vegas, the International Gaming Institute (which exists in part because of a bequest by one of the fathers of the video slot machine industry) just released a 15-page report on the economic impact of a casino on the GTA. While the document is all dressed up as something sober and academically rigorous, it was bankrolled by the Canadian Gaming Association, whose membership roster includes MGM and Caesars International.

After sifting through the “complex claims made by various stakeholders,” the study’s authors came to the admittedly unsurprising conclusion that an integrated casino-resort will have a generally positive economic impact, including on property values in the vicinity of the resort.

This last conclusion derives from a rather remarkable comparison, as the report cites a 2011 study on the “complementary” impact of Detroit’s casino on surrounding retail and real estate, which, it goes on to say, “provides a relatively meaningful case to compare to the proposed Toronto project.”

Huh? The area around Detroit’s casino is “Greektown,” a few theme-park style blocks of tarted-up eateries that cater exclusively to stranded conventioneers and casino-goers, and bears no resemblance to the functioning multi-purpose city streets found near the proposed casino sites in Toronto.

Quite apart from such torque, the sunny image of the casino industry isn’t always reflected in the financial disclosures of the gaming companies themselves. Indeed, since the 2008 meltdown, several heavily over-leveraged gaming giants had a tough ride after building huge resort-casinos in Macau and various U.S. locales.

In fiscal 2011, the Las Vegas Sands, which trades on the New York Stock Exchange, generated $9.4 billion in net revenues and $3.5 billion in earnings (before taxes and other charges). But the company, which has resorts in Las Vegas, Pennsylvania, Macau and Singapore, told its investors it had to “suspend portions of our development projects” due to the uncertain economy.

For the same year, Caesar’s, which trades on NASDAQ and has a partnership with The Stronach Group, generated $8.8 billion in revenues, yet managed to turn a net loss of almost $700 million, with declining business in Atlantic City and Mississippi. The firm, which has 52 casinos worldwide, lost over half a billion dollars in the third quarter of fiscal 2012, up sharply from the same period in 2011.

Over at MGM, the company has accumulated over $540 million in losses in the first nine months of fiscal 2012, a dramatic reversal from the year previous. Even Sheldon Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands saw a 15.6% decrease in net income in Q3 2012 compared to a year previous, although his firm is still in the black due to the massive flow of money into the Sands’ casino resorts in Macau (which keeps the entire sector afloat).

A few regions with new casinos have seen upswings in traffic. Pennsylvania’s gaming sector has been on a roll for six years, and last year generated a record gain. (As one Allentown media outlet trenchantly put it, “People lost a record $2.5 billion at the slot machines at Pennsylvania casinos in 2012, a nearly 3 percent increase over 2011.”) But Atlantic City saw an 8% decline in 2012, said a January report in Reuters, which cited statistics from the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement.

In New York State, where governor Andrew Cuomo is pushing for three new casinos in central and upstate regions while the gaming industry wants a New York City location, a recent investigation by the McClatchy Newspaper chain found that the promised casino revenue in several states has a way of falling short of the mark. The survey, according to reports in Albany’s Daily Gazette, found that Florida casino revenues were 80% below the amounts initially promised, while in Colorado only a fraction of the funds promised for educational institutions materialized.

This fuzziness around the revenue figures has other tendrils as well. That UNLV study cited above repeats one of the most commonly sited bromides meant to mollify the anti-gambling set: that a large portion of the casino-resort revenues will actually come from other sources, like retail and restaurants (read: untainted money). “Companies that have expressed interest in bidding on a Toronto casino license have casino resorts that derive upwards of 60% of revenues from non-gaming amenities (e.g. MGM Resorts International, 2012; Wynn Resorts, 2012).”

Okay, but now consider this: two of the big firms vying for a Toronto location – Las Vegas Sands and Caesar’s – derived 70 and 75% of their net revenues for fiscal 2011 from gaming (as opposed to convention bookings, hotel rooms, etc.). So all this talk about the gaming being only a small piece of the pie may be just that: talk.

The financial performance of the casino industry obviously has a bearing on the discussion that will take place at council. If revenues fall short of promises, the city will earn less hosting fee income (acknowledging that the exact formula has yet to be determined). What’s more, if OLG chooses a casino firm that’s facing financial difficulties or is in the midst of a very large and expensive development project elsewhere, the company may end up pushing back against onerous urban design conditions intended to make the deal more palatable – e.g., below-grade parking.

Lastly, there’s the pulled plug scenario, as happened this fall when Hard Rock International scotched plans for a $300 million casino in Atlantic City following heavy losses at Revel’s $2.4 billion complex, as the Philadelphia Inquirer reported.

Unlikely here? As Wikipedia’s impressive listing of cancelled Las Vegas casinos suggests, the gaming industry — which is all about knowing when to hold ‘em and when to fold ‘em — apparently has never been shy about cutting its losses.

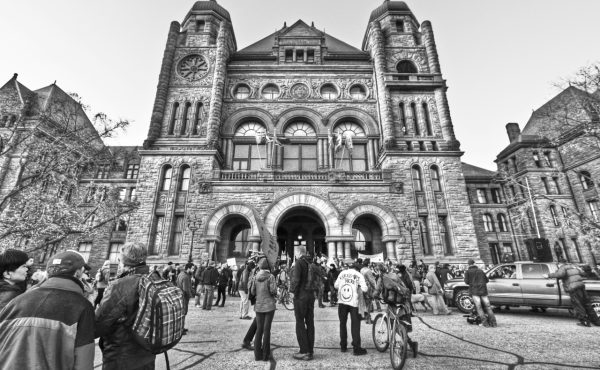

photo by Travis Isaacs

One comment

In summary, the report is not based on data and advised that its data is insufficient.

The research report is largely editorial and is not based on rigorous analysis or research.

It draws a conclusion while at the same time, saying it does not have data to draw such a conclusion, which makes this report illogical.

Despite the authors having PhDs, no rigorous analysis was ever made or attempted in conducting any primary research or anhy panel studies for sites such as Las Vegas, Atlantic City, New York, Macau, Nice/Italy or other locations – typically 20 cities should be conducted in a panel study for reliable and validity testing. However, they did not attempt to do this before writing this report.

The city council should not base its decision based on this report because it is logically flawed and also not reliable.

Interestingly, the title “informing the public dabate” the title of this report, does not do this. it reiterates that it has not enough information to draw any conclusions despite the title, which therefore is misleading in itself.