When I arrived at Saving Gigi to meet Craig Morrison, founding teacher of the Oasis Skateboard Factory, I almost didn’t recognize him. Tall, bearded, and dressed in black, he looked nothing like any teacher I’d met before. But then the Oasis Skateboard Factory is unlike any school I’ve heard of.

Craig founded the organization, the world’s first skateboard design school, three years ago. After a long stint as an art teacher, the 45-year old developed a unique class at the Toronto’s Oasis Alternative Secondary School that blended students’ passion for skateboarding with the development of transferable creative and entrepreneurial skills. Craig quickly realized the potential for learning through skateboards, and pitched the plan to the school board as a one-year re-engagement program for at-risk youth.

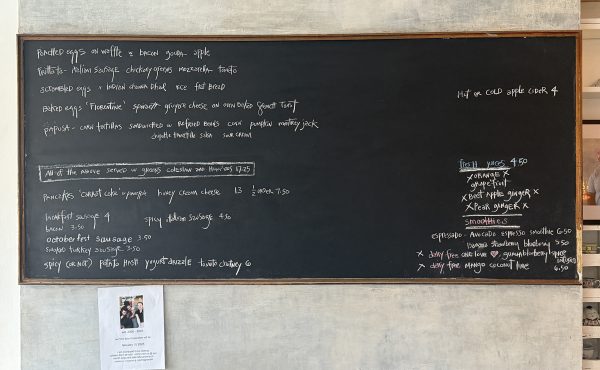

Each year, 18 youths, aged 16 to 19, work collaboratively, engaging local clients in the design and development of a personalized skateboard. The boards can be found on display at many local independent businesses, including Saving Gigi and Kensington Market’s Longboard Living. Throughout the process, students develop real world skills that they can put to use right away.

“Kids are often told that they have to study something because they will eventually need the knowledge. I say ‘We’re doing this now.’ No one hands me something that I only mark and put in a folder. Everything we do is public: in the street, in a gallery, in pop-up shops, and at product launches,” says Morrison. These are kids who have been told to stop drawing in the margins — Morrison helps them identify their talents and turn them into something incredible.

Consequently, the school attracts a unique kind of student. “Many of these kids haven’t previously been successful in school, and they feel like adults shut down any opportunities for fun or for their creative input,” says Morrison. “I get to shove my foot in the slamming door.” Students not only benefit from the chance to earn credits doing what they love, they also earn an honorarium for their efforts.

The program draws students from across the city; Morrison notes that only one of his students lives close enough to skateboard to school. While students convene at Scadding Court Community Centre, “we’re actually not in our classroom very much,” Morrison notes. “We’re often out in the world. Prior to the program, a lot of my students felt like they were disconnected from the community. The feeling of being connected gives them a lot of confidence.” Seeing their work acknowledged by the broader community, students begin to see themselves as participants in the city.

The school is very much based in the local economy, as Morrison has an open invitation to the wider community to be a part of the program. By working with local businesses, students have another opportunity to develop relationships with local entrepreneurs and mentors.

“Up until this point, my students have been told that everything skateboard-related has to come from California, even though Canadian maple is the best material to manufacture skateboards with,” says Morrison. “We make handcrafted artisanal skateboards — this is extremely powerful for kids who haven’t used their hands to make anything before.”

Morrison sees himself less as teacher and more as captain of a pirate ship. “My students tend to ignore the rules. They imagine how things could be done differently, including the architecture of this city.”

Next school year, through legal graffiti projects, workshops, murals, and gallery and pop-up shows, Morrison’s students will continue to shape their city.

This article originally appeared in the fall 2012 issue of Spacing