Toronto 2015 is a complex political landscape. We have private money frantically building new developments, yet we have tremendous public infrastructure, affordable housing, and public space needs and not enough money committed to build them. On the operations side, the City is constantly stretched for funds, resulting in huge pressure on public institutions and agencies to cut services and close facilities. This private boom and public bust environment means we are having to advocate for the public good in ways that require more creativity and sophistication than in the past.

David Hulchanski’s Three Cities Within Toronto work shows the power of a good map to clearly tell the story of inequity in our city. The new urban activist toolkit needs citizen science, open data, maps, graphic design, and mash-ups so we can effectively advocate for change.

This new urban savvy is a daunting proposition — it’s data-, technology-, and graphics-intensive. But if we want a sustainable, equitable, and public Toronto, we need to find ways to effectively speak up for the public good with kick-ass data and graphics.

In the environmental movement, intervenor funding exists to help level the playing field for citizen participation in environmental assessment hearings and tribunals. It would be easy to stop here and say we need money, but in the time it takes for that money to arrive, more TDSB schools will be closed and sold to developers, more condos will be built with a crappy public realm around them, and we’ll be no further ahead.

In the short-term future what Toronto needs is a volunteer gang of data, map, and infographic aficionados who can be deployed quickly to help people advocate clearly and effectively for the change they want. While the prospects of organizing these folks may seem daunting, the raw material in terms of talent, skills, and knowledge is abundant in Toronto.

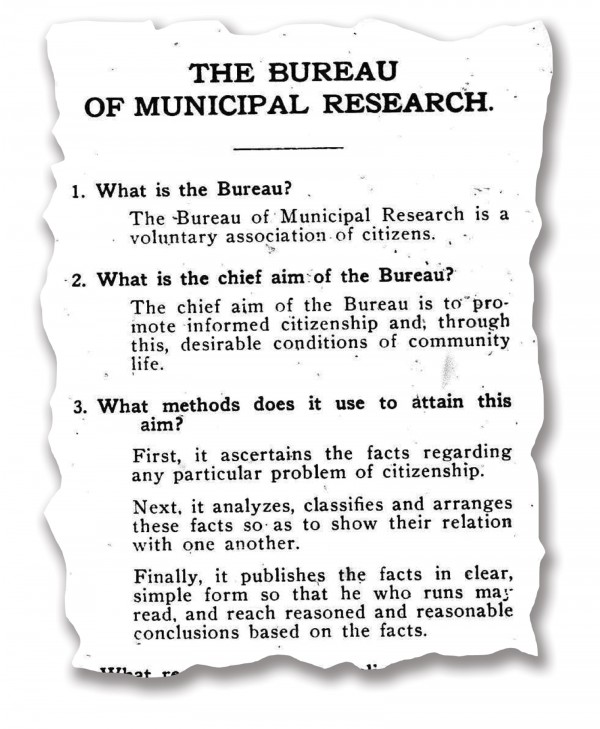

Interestingly enough, Toronto once had such an organization. In 1913, Samuel Morley Wickett founded Toronto’s Bureau of Municipal Research. The Bureau’s Q&A pamphlet (shown above) shows that, until the 1980s, this organization sought to do some of the work we once again need today.

A few years back, Dave Meslin wrote about reinstating the Bureau. More recently, Gabriel Eidelman, an assistant professor at the School of Public Policy and Governance at U of T, has been cataloguing the 830 documents the Bureau published from 1914 to 1983. He is keen to talk to others interested in its revival.

As a university professor, I see opportunities too. In planning programs across the region, all of our students do some kind of project that connects their research and skills with community needs. At our school in any given semester, we have 12 or more client-based studios underway. But these projects have long lead times and sometimes emerge from existing networks and relationships. We need additional options with quicker turnaround.

What if someone invented a course for students where credit was earned by being ready, waiting, and able to respond week-by-week to community research and graphics needs? Course learning objective: help someone do something now. If you’re an educator and you think, “That course would be chaos to administer,” then don’t volunteer to teach it. If you’re a learner and this idea appeals, ask someone where you are currently learning to make it happen.

What if ordinary assignments could align with community needs? Say a student has a stats assignment, and across town a community group needs some data crunched. What if we had an app to match these needs up? For those of us who work with students, the question is “how can we connect their learning with pressing community need?”

We’ve got a city keen on hackathons and app contests. This sleeves-rolled-up, work-together spirit is at the heart of what our city needs more of. We once had transit camp, and now Meghan Hellstern at MaRS is working on a civic design camp initiative. If you look at where these kinds of events are being held, you see many are held in the downtown core. Let’s take these gatherings and make them portable and deployable on short notice. Rexdale Lab is doing this kind of work in the group’s own neighbourhood. Until more neighbourhoods have their own capacity, a mobile team of volunteers could come over and help.

These ideas are not a surrender to austere government or a pragmatic resignation to further downloading onto community groups. I’m not suggesting that precariously employed-yet-skilled urbanists should perpetually work for free. I’m arguing here that the future of our city depends on us making the most of what we’ve got by putting our assets to work for the public good. In an increasingly diverse Toronto, one-size activism doesn’t fit all. This communication-savvy, civic volunteerism deployed where people need it could be at the heart of a better Toronto.

Pamela Robinson is a contributing editor to Spacing, an associate professor in the School of Urban and Regional Planning at Ryerson University, and is a member of the board of directors for the Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation

One comment

Great article, Pamela. I’d love to see the Municipal Bureau of Research resurrected.

Thanks for mentioning Civic Design Camp as well! If you want to learn more, please check out http://civicdesigncamp.ca – Canada’s first Civic Design Camp is happening June 26th at MaRS and promises to be a full day of learning, sharing and building the civic design community in Toronto and hopefully beyond.

If anyone thoughts on how to help make events like Civic Design Camp have more impact beyond the downtown core please feel free to share them, since, as Pamela writes, “…the future of our city depends on us making the most of what we’ve got by putting our assets to work for the public good.”