When I went on Kijiji Thursday morning, I quickly found the following listing: a basement apartment in a bungalow for $515 a month, to share with two other male tenants. It is located in a part of the city (North York) where so-called “secondary suites” are legal, but rooming houses are not (for now).

Less clear is whether this unit, like thousands of others across Toronto and the GTA, complies with the existing fire, health, and building code regulations that ostensibly exist to protect tenants, but are routinely flouted by landlords trying to cut corners. The price suggests a compliance challenged environment, to say the least.

Anecdotally, there’s been a huge increase in the number of such grey-zone apartments — sort of legal, sort of not — for reasons that have everything to do with the lunacy of Toronto’s housing market. Real estate prices are skyrocketing and buyers are betting the farm on outrageously expensive homes or condos in the hopes that their investment will deliver some kind of future pay-off.

At the same time, rents in the private market are soaring, largely because of the dearth of new rental units and gentrification in downtown neighbourhoods that once had plenty of rooming houses. But if you’re up to your earlobes in a mortgage you’ll never pay off, there’s a powerful incentive to do a quick-and-dirty basement conversion and defray some of those crushing monthly costs with rental income.

But while basement units and illegal or semi-legal rooming houses represent a substantial and indeed important segment of the affordable housing sector, the City can’t really say how many Torontonians are living in such dwellings; existing statistics show that about 50% of the city’s residents live in detached or semi-detached houses, but they don’t reveal the proportion of owners versus tenants.

Nor does the City know, with any accuracy, whether such units meet safety or health requirements. Tenants can complain to the City if they’re concerned, and municipal inspectors, once engaged, will force landlords to make improvements or face steep fines and even jail time. But the onus, clearly, is on the occupant, who may or may not have the language skills, wherewithal, or courage to take on a landlord (The Fire Department has stepped up inspections and encourages tenants to call if they have concerns).

Sometimes, as I reported in The Globe and Mail last weekend, tenants do die in blazes in buildings with no working smoke detectors, blocked fire exits, or old and deficient wiring (the numbers aren’t large but each one is a tragedy and some, like the three young people who died in an illegal Whitby, Ont., rooming house in 2012, are truly horrific). Many others find themselves exposed to mold, bug and rodent infestations, poor air circulation, crumbling asbestos, and so on.

The question is whether the City has the capacity to encourage the owners of such units to invest in improvements without creating unintended consequences.

On her Opening the Window blog this week, housing consultant Joy Connelly argues for re-branding rooming houses as “shared houses,” as well as a regulatory environment that doesn’t inadvertently force out small landlords who can’t afford to bring their apartments up to existing codes. As she correctly notes, far more people die each year due to homelessness than in apartment fires, so it’s important to ensure that the cure isn’t worse than the disease.

It’s not clear how a flexible regulatory environment would look and function, and even whether the existence of one set of safety rules for homeowners with secondary suites or rooming house operators, and another for commercial or non-profit apartment building owners, is politically or legally sustainable.

From time to time, the City looks at creating financial incentives for landlords, such as with renovation grants in exchange for commitments from the property owner to maintain rents at an affordable level for extended periods. But such measures are destined to be severely limited by the availability of overall funding, paperwork and the conditions placed on such grants.

I’d argue that there’s another point of leverage — besides the carrot and the stick — that hasn’t been adequately explored. At present, it’s easy to go on line and find reams of information about rental apartments. But there’s no way for tenants or prospective tenants to find information about whether those apartments have been subject to fire, health, or building code inspections and the outcome of such orders.

All that information is in the public realm, especially if the original complaint came through a 311 call. But when I spoke to Municipal Licensing and Standards officials for my Globe story, they acknowledged that those records are not all in one place – fire inspections, building code violations, and other such data sets are not linked to one another, and don’t even seem to be part of the City’s open data releases.

Obviously, there may be legitimate privacy concerns in making available some of these kinds of records. But if the City is serious about improving Toronto’s affordable housing stock, of which such apartments are clearly a component, there is surely a public policy rationale for allowing tenants to have ready (which is to say, online) access to information already in the public domain.

Also, it’s not necessarily the case that the City itself should be figuring out how to package and make available this kind of data. In New York City, for example, an upstart firm called RentLogic is culling all sorts of rental housing information from open data releases, and has developed an interface that allows tenants to use filters like mold, infestation, and other conditions when checking out apartments.

According to founder and CEO Yale Fox, New York is the “gold standard” for open data, and these releases allow app developers and entrepreneurs in the so-called “civic tech” sector to create ways of using municipal information to confront stubborn social problems like the proliferation of over-priced, unsafe apartments. “When we started RentLogic,” Fox told me, “we said everything is about the renter.”

He offered up this warning: “Toronto is like a baby New York” in terms of the precipitous decline in landlord-tenant relations, deteriorating apartment conditions and out-of-control rents. “Toronto is on that path.”

illustration by Matthew Blackett; modified from Shutterstock

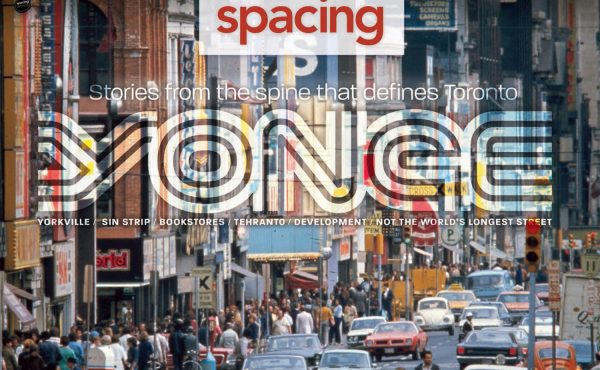

The new Spring 2016 issue of Spacing is out on newsstands now. Check out our cover section on Toronto housing issues. You can also find a feature-length profile by senior editor John Lorinc on Canada’s largest urban archaeology dig happening right beside Toronto City Hall.

The new Spring 2016 issue of Spacing is out on newsstands now. Check out our cover section on Toronto housing issues. You can also find a feature-length profile by senior editor John Lorinc on Canada’s largest urban archaeology dig happening right beside Toronto City Hall.

Don’t miss an issue of Spacing by subscribing for four or eight issues.

3 comments

People who are interested in this idea might want to check out the City of Vancouver’s version, which is a few years old now. Lots of details here:

http://vancouver.ca/people-programs/rental-standards.aspx

John,

Would it be fair game for the city to provide the data to allow Landlords to know about problem tenants? Having a problem tenant who can game the system can cause brutal amounts of heartache and grief for a small-time Landlord. And tenants get quite a bit of protection.

Interesting perspective, John, and one worth pursuing.

I looked up the Vancouver website Karen suggested. It’s nicely organized and easy to use. The limitations: it excludes secondary suites, lane way housing, duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes, condos and most important, any buildings without a rental licence. Also it was hard to interpret just how serious some of the violations were. (I note this because I’m familiar with a church that has just been cited for some code violations, but is clean, navigable and has safely operated for 100 years.)

Also, wondered why you think different rules for second suites, rooming houses and commercial operations would not be “politically or legally sustainable.” It’s the situation we have now. For me, the real question is why a family home with a couple and two children suddenly becomes illegal in Scarborough or North York — or requires an $100K upgrade downtown — if the family is replaced with four adults who happen to pay rent separately.