When I asked Anders Lie, the Swedish expert on the Vision Zero traffic safety program, about cities (like Toronto) where politicians lay claim to the “Vision Zero” brand without following through with their actions, he said, “You cannot talk fatalities down.”

Those nations and cities that have truly embraced the Vision Zero program for traffic safety have seen concrete, consistent declines in the number of people killed and seriously injuried in traffic collisions. But the program takes a real investment, not just of money, but also of political capital in committing to difficult policy changes, like building sidewalks on all streets, creating a real network of bike lanes, and reducing speeds on major streets as well as local ones — none of which Toronto’s politicians have shown a commitment to.

Lie’s quote came at the end of a panel discussion about Vision Zero at the recent International Transport Forum summit in Leipzig, Germany. During the panel, Lie talked about the philosophy of Vision Zero, which accepts that humans will make errors and seeks to build infrastructure that will minimize the consequences of those errors. He talked about avoiding the “mind trap”: even if 95% of collisions are the result of human error, that doesn’t mean 95% of the solution is changing human behaviour — the system needs to have a certain amount of tolerance for error built into it. Lie also advocated avoiding a single-minded focus on “zero”, which he said can lead to complicated arguments that paralyze action, and instead start with aiming for “close to zero”.

(For more information, see the ITF report, Zero Road Deaths and Serious Injuries: Leading a Paradigm Shift to a Safe System)

It was just one of many interesting insights and debates about walking and cycling policy that I heard at the conference.

Focus on appeal, not just safety

At the same panel, Alexandre Santacreu, a road safety analyst with the International Transport Forum’s “Safer City Streets” initiative, emphasized that encouraging walking and cycling involved much more than just avoiding deaths and injuries. People have to feel safe as well — one cannot have policies that promote cycling and walking if people are scared. It was a slightly different point of view from the other presenters, including Lie, who focused on reducing serious accidents; in a sense, even the threat of minor accidents or discomfort can also discourage active transportation, which is so much more exposed to and unprotected from its environment.

This issue can be a limitation of Vision Zero, which focuses on deaths and serious injuries. If a particular sidewalk or route is safe from serious traffic collisions, but unpleasant to use for other reasons such as a poor maintenance or an ugly environment, or even the threat of minor collisions, it still will not encourage walking and cycling. Vision Zero is a start, but it is not sufficient.

(Note: Toronto is not yet part of the Safer City Streets initiative, but Montreal is)

Is Vision Zero relevant to developing nations?

During the questions at the Vision Zero panel, a planner from Argentina made an impassioned intervention that questioned whether Vision Zero was really relevant to developing nations that are starting from much higher rates of traffic fatalities. A Thai journalist I talked to asked the same question.

At the heart of their question was whether Vision Zero is starting from certain assumptions about road behaviour that are present in developed nations but not yet widespread in other nations. Does it implicitly count on road users behaving in certain ways? Vision Zero tries to allow for human mistakes, but do changes in behaviour need to happen first for Vision Zero to work?

On the other hand, in the 1960s, Sweden’s level of traffic fatalities was similar to that of many developing nations now. So it is clearly possible to reduce fatalities dramatically from those levels over the course of decades. As the Vision Zero program expands in developed nations, its next step may be to learn to adapt to nations that are starting from a much higher rate of fatalities.

Reversing the safety onus

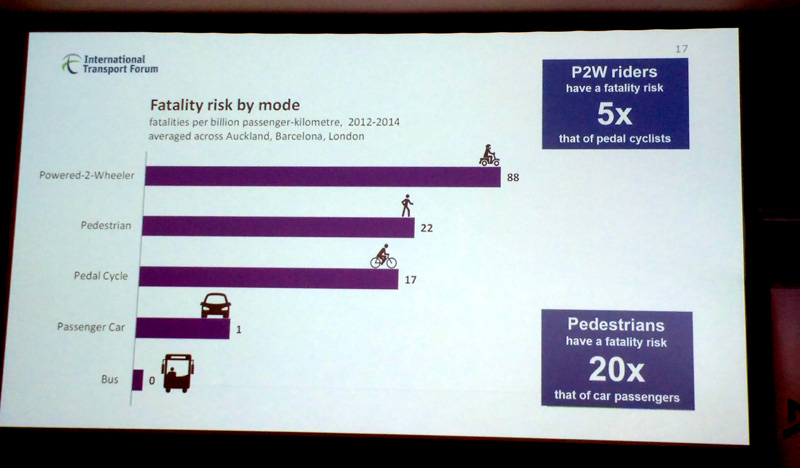

At the same panel, there was a lot of discussion of this chart, which shows that, in cities, pedestrians and cyclists are much more vulnerable to being killed than drivers when calculated in terms of fatalities per total kilometres travelled (though mopeds and motorcycles are the most dangerous forms of travel). Audience members were concerned that these statistics could unintentionally discourage active transportation.

The panelists noted that even with these higher risks, walking and cycling are better for people’s health overall than other modes of transport. The overall health benefits greatly outweigh the risk of injury or death.

But an audience member had a more interesting idea: why not reverse the statistics to show the risk each mode of transport imposes on others? The chart would be effectively turned upside down, with cars being the form of transport that imposes the greatest risk, transit somewhat risky, cycling marginally risky, and pedestrians coming in at essentially zero risk imposed.

Bike parking is an issue

A charming moment at the summit happened when a Dutch presenter and audience members at a session on the decarbonization of transport started to compare the number of bikes they owned (3, 3 and 2, respectively). Active transportation (cycling and walking) is approaching a 50% mode share in the Netherlands. But the presenter also noted that bicycles “are not only a solution, but also a problem.” He said that one of his nation’s major challenges was creating enough bike parking at train stations to cope with the volume of demand.

In another session, another Dutch presenter noted that the nation faced a problem when local governments were given responsibility for cycling, because it was hard for them to fund the cost of bike parking at train stations, which could be up to 3,000 Euros per spot — cheaper than parking for cars, but still an expense.

At the first plenary discussion of the meeting, meanwhile, China’s Minister of Transport, Xiaoping Li, noted that one of his nation’s significant transport issues was the proliferation of private bike-share companies in large cities, especially in terms of parking. These shared bikes can be left anywhere, and they end up piled up at major destinations, blocking passage and access. His government is working on regulations to cope with the problem.

Bikes take a lot less parking space than cars, but they still need to be parked. One takeaway was that, in nations or cities with very high volumes of bike use, bike parking can be a significant issue.

Shared transportation needs active transportation

At a presentation of a report, Three Revolutions in Urban Transportation, Ramon Cruz of the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy emphasized that, to get the best out of the three innovations of electric, automated, and shared vehicles, a government would need to aggressively invest in transit, walking and cycling as well to achieve the goals of reducing carbon emissions and congestion.

The key is that car sharing won’t take off without transit and active transportation. If you need to use a car every day, you are going to buy one, not use a shared car. For car sharing to work, it has to be something people use occasionally, for particular type of trips, while relying on transit, walking and cycling for their day-to-day activities.

And, without car sharing, the study shows, the advent of electric and automated vehicles will simply lead to more use of private vehicles and therefore more congestion (even if automated vehicles are a bit more efficient in how they use the road). When these two innovations are combined with car sharing, however, it means that cities can enjoy just as much mobility but with fewer vehicles on the road — which, in a virtuous circle, allows roads to be narrowed to give more space to walking, cycling and transit. For car sharing to take off, however, it needs active intervention and investment from governments, for example through compact development, efficient parking, a per-km vehicle tax (to discourage empty vehicles driving around waiting to be used), and investments in transit, walking and cycling.

At a later panel discussion, a panelist summed up this issue with a quip that a truly “smart” car would tell a customer to get out and walk or cycle for a short trip: “I am a wonder of technology and you are wasting my time!”

2 comments

The comments about third world countries betray a lack of understanding of Vision Zero. The primary method of achieving safety is through protective infrastructure, since human beings will always make mistakes. Concrete and steel work just as well in third world countries as they do in Canada.

For example, see this “cyclopista” (Spanish for cycletrack) next to a rural highway in Mexico:

https://www.google.ca/maps/@20.2885184,-103.3184399,3a,75y,270h,90t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sGB30PgPscKx0iQ2HB2AOMw!2e0!7i13312!8i6656

Quite frankly, I would much rather be riding there than on the shoulder of any rural highway in Ontario.

The problem with this chart is the statistics are reported as fatalities per kilometre – this is the false equivalency of mode share and distance. Most people will never walk as far as they drive, obviously the speed of cars aids in the ability to make much longer trips, and more km’s equals more risk. Therefore, the chart is completely misleading, unless the average Canadian walks or cycles the average 20,000km that the average person drives in their car annually. A better metric is “trips”, which helps offset the bias of mode share distance.