In cities the world over, streets are being repurposed for people walking, cycling, and simply spending time outside. First Milan, Bogota, then Oakland, Lima, Paris, New York, London. The list goes on. From east to west, Canadian cities are setting out similar plans. So how should cities start to re-plan their streets? Here is a four-step guide for our cities.

STEP 1: MAKE THE CASE

This crisis has been all about political leadership — a willingness to hear, challenge and explain the science, to trust in it, and act accordingly. Leadership starts with defining the problem. City leaders must start with setting out the problems our streets face and building consensus on the need to act. Mayors need to lead with the following three simple reasons:

Relieve the squeeze on public space

The two metre rule has increased the amount of space we all take up. There is less of it to go around. Our sidewalks feel narrower. Our bike lanes (where they exist) are now shared with runners and people avoiding each other. And our much quieter traffic lanes have also become a relatively safe space to dart into to avoid oncoming people (even with speeding and ‘stunt driving’ offenses up dramatically). Space is squeezed and it needs some relief.

Keep essential journeys moving

Essential workers are still traversing cities every day to get to work and are doing so under increasingly stressful conditions. The highly contagious virus has relegated transit to the option of last choice for those that have the luxury of alternatives. Public Health officials are rightly urging those who can bike or walk to do so and free up seats on public transit for those who can’t. But with already poor conditions for cycling and walking in much of our urban landscape, our cities need to act fast. Creating new space for cyclists and pedestrians helps essential workers and everyone else trying to get supplies, to get to medical appointments or to care for others.

Follow a vision for a better city or face a tidal wave of cars

Our cities now face the very imminent threat of a tidal wave of car traffic. As people have been warned off transit and services have been reduced, the car is becoming an appealing option for those who can afford it. But that would be disastrous for our cities: even if travel demand doesn’t return in the same way, a small shift to the car can have a major effect on road danger, air pollution, and congestion. Many urban citizens are finding silver linings to the crisis in the newfound silence at night time, hearing birdsong for the first time in mornings and the freedom to cross a road with ease. These are positives people rightly want to keep.

Commercial goods traffic might not so easily be shifted, though it can be dramatically improved. Yet commercial movement will also suffer if people take to private cars en mass and start to clog our streets again. Preventing this and planning for the alternatives is vital.

Good mayors and city-leaders around the world are making this case to their constituents. Building consensus for action is clearly the first step in reorganizing our streets in a more humane way. We need more space, we need alternatives for essential journeys, and we want our cities to be better places when life returns to a semblance of normalcy. Mayors have to lead with this case.

STEP 2: INVOLVE PEOPLE & LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

Involving people, community groups and organizations is important in any decision-making. But particularly so now as a lot of the data about how people are travelling and using our streets has been made redundant by the stay home order. Social distancing clearly poses challenges to involvement in decision-making, but the shift to virtual tools is necessary (even if not perfect). Cities need to work even harder to involve people and in return build support and advocacy for measures that address our concerns and allow us to influence plans before they are made in detail.

Over the months of lockdown, we’ve all developed intimate knowledge of our local journeys to get essentials. Since residents know their own neighbourhoods in detail, organizations and representative groups will have a clear understanding of the issues affecting their constituents. They need to be engaged. Walk Toronto has already crowd sourced data on pedestrian pinch points in their city, while cycling groups the world over are recommending strategic routes. Many neighbourhood groups are already using their streets as community spaces, enjoying the newfound quiet to cheer for health workers. Involving individuals, community — including newly sprung up mutual aid groups — and organizations provides essential information for planning in a time of change. Tapping local knowledge is more necessary than ever.

Of course, there will be NIMBYs. Yet there will also be YIMBYs. Through deep and extensive involvement, we can make the distinction between the vocal minority and the rest, as well as address some of the underlying concerns that often lead to NIMBYism. The most effective and successful city projects often emerge where the challenge and scrutiny has been greatest.

STEP 3: DEFINE YOUR STREETS

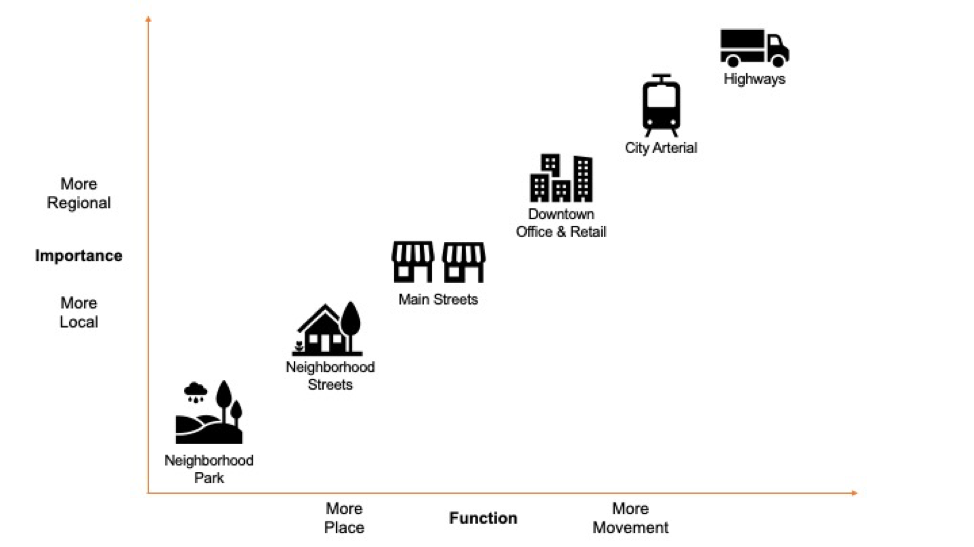

If they haven’t already, cities need to define their streets and what they are for. A major arterial — a mini-highway in the city — requires a different response than a quiet residential street or a store-lined main street. The two components cities ought to consider — the two-axes that help us determine a response — are function (what is it for?) and importance (how many people need to use it for each function?).

Function means asking if a street is primarily for movement, or primarily a place. How much time are people spending on this street (or would they if it was more welcoming)? At one end is the place-oriented street, typically a main street and destination for services and shopping. At the other, a movement-oriented street, such as major arterials, key city-wide corridors and highways. Determining an answer to this helps us think about what level of vehicle traffic is tolerable, how essential transit is, and how much space to give over to other uses (bear in mind cafes, bars and restaurants are more likely to come back as ‘outdoor’ venues than indoor).

Importance means asking how strategic a street is to your city. If this street is about movement, or destination, or somewhere in the middle, how important is that function to the city as a whole? What examples from your city might fit into these categories?

The pandemic has heightened the role of our residential streets (those on the bottom left of the graphic above). In the absence of outdoor “backyard” space, they have become a communal space for whatever use we feel like — ball hockey, impromptu dance party, or just socializing (at a distance). Cities aiming to create quiet streets should support these kinds of activities, as well as neighbourhood walking or cycling to access the local stores and services and form part of the city-wide network of bikeable streets.

Our local, neighbourhood streets are where we don’t really need traffic, only access. We should begin by closing them off to through traffic, saving vehicle access for residents and services and keeping through traffic on the streets designed for it. Taking an area-wide approach, rather than street by street, creates truly quiet streets without burdening other streets in the neighbourhood with any extra traffic. This approach is a central plank to city building in the Netherlands and Barcelona’s superblocks, and I’ve seen it’s transformational effects first hand in London. Cities need to not only define their streets, but define neighbourhoods, close them off to through-traffic and open them up for people. If cities want to create quiet streets, they need to plan at the neighbourhood level.

It goes without saying that protected bike lanes need to be added to streets where movement is a greater priority (with the exception of our highways of course). Many will need wider sidewalks, too, particular the main street sections where the buildings are in use, and need the space for line-ups of to serve people at a distance through doors and windows.

With this broad menu of street and treatments set out, the question is then, where first?

STEP 4: DECIDE WHAT PLACES TO PRIORITIZE

While city dwellers’ travel patterns might have changed dramatically, where they live hasn’t (mostly). Streets that need addressing first are those where the need is greatest. This is where cities can be data-led. Using criteria like population density, access to, and quality of, open and green space and household income can inform the prioritisation process. Denser areas obviously place more pressure on streets and services, while those without access to outdoor space deserve somewhere to get out, exercise and support mental health. Lastly, income is vitally important as those with lower incomes tend to live in smaller dwellings, without access to a car and yet unduly suffer the impacts of car culture and isolation orders. Using these data points, cities can begin to roll-out measures according to need, rather than simply responding to the loudest voices, or the easiest wins.

STEP 5: TAKE ACTION & SEEK FEEDBACK

Any street changes need to be adaptable, quick and cheap. There is the potential for new hot spots of activity to open-up as restrictions are eased or streets to go quiet again if the reverse happens. Over the coming weeks, more businesses that open-up could mean more line-ups, and more people cycling in new parts of the city or streets. Cities will need to be ready to respond and remake their plans, quickly, and will need to have a process in place to take on feedback, tweak and improve along the way.

By leading and making the case, involving citizens in the process, defining our streets and what we want from them, and acting quickly and nimbly, municipalities can begin the process of recovery and find some small positives emerging from the crisis in the more humane and healthy streets we build.

Our streets are one of the most valuable and malleable assets that cities own right now — doing nothing will perpetuate, if not worsen, the existing inequalities the pandemic has brutally exposed. Changing our streets might just help us recover to a more liveable city on the other side of the lock down.

Canadian cities now need to seriously think the role of their streets and the place for vehicle traffic within them. The nimblest and most visionary ones will be the short- and long-term success stories.

Nick is an independent policy and communications consultant from the UK, currently working out of Toronto, specializing in transport and environment issues. Follow him on Twitter @Nicholas_I_S

photos by Roozbeh Rokni; Michael Swan; Can Pac Swire