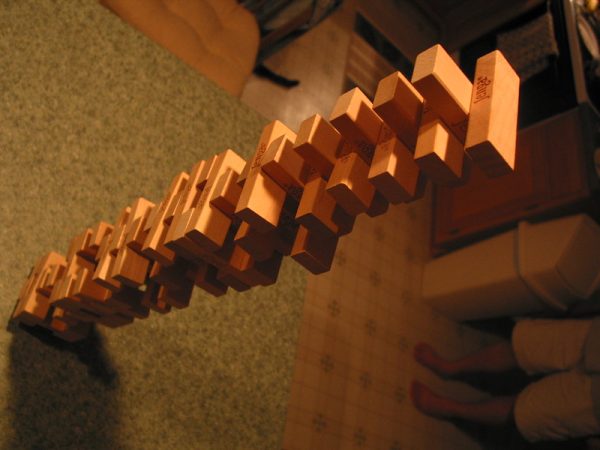

For some years, I worked for an organization that practiced what I came to think of as the Jenga school of management. The organization loved to hire prestigious new employees, set up impressive-sounding new management positions, and embark on ambitious, glamorous new initiatives. Unfortunately, it was also tight on resources. So to help cover the costs, it eliminated unexciting administrative positions filled by unglamorous people who did the organization’s day-to-day work (including, eventually, my position). The result was that the organization got worse and worse at providing basic, core services, and highly-skilled, highly-paid people ended up wasting a lot of their time on routine tasks. Meanwhile, many of the high-flying new initiatives faded away for lack of support after their splashy initial launch.

As in the game Jenga, the organization kept removing the basic supports that kept the whole thing going in order to try to reach impressive-looking new heights. But the higher it reached, the more unstable it became.

At some point, I realized that this Jenga management principle could be seen more universally – and, in particular, at Toronto City Hall. For most of its existence, the amalgamated City of Toronto has kept tax increases, and therefore its revenue increases, low. That has not stopped the City from constantly coming up with new initiatives and projects. But since it’s not bringing in enough new money, to pay for these new initiatives – and to provide the staff needed to support them – it has steadily cannibalized the unglamorous but basic functions of city government. Maintenance is deferred, retiring staff who do the everyday work aren’t replaced, basic functions are increasingly neglected. Meanwhile, the new initiatives themselves often remain unfunded, lack funds for maintenance, or trail off into ineffectiveness.

“On its website, the city says: ‘Please be advised that the Diving Board, Spa, Slide, Swing Rope and Leisure Pool Features are currently not operational. We apologize for any inconvenience this may cause.’”

And missing from this pledge to fix: a deadline https://t.co/9SsxNV0H4e

— Matt Elliott (@GraphicMatt) October 4, 2022

The City is not short of new initiatives. TransformTO is supposed to bring the city to net-zero carbon emissions. Vision Zero is supposed to eliminate traffic deaths. Housing Now is supposed to build significant amounts of affordable housing. Ambitious new rail transit lines, some underway and some merely line items in a plan, are supposed to get Toronto moving. The Ravines Strategy is supposed to revitalize our riverine green spaces. The cycle plan is supposed to get Torontonians pedalling all over the city. And so on. There’s a plan for everything.

But the city’s budget tells a different story, as does one’s overall experience of the city. All those initiatives are being piled on top of an increasingly wobbly base.

Even as we build new transit lines, the deferred maintenance for keeping the existing transit system running piles up, leaving it ever more fragile.

Even as we build the occasional nice new park or transform one or two existing ones with developer money, the City plans for a gradual run-down of existing parks as the Parks budget flatlines in the face of increasing costs and population. As many people noted this summer, water fountains don’t work, what few public toilets there are stay locked up most of the year.

Basic municipal services, such as removing dead animals and emptying waste bins, become ever less reliable.

Please note that Animal Services is extremely back-logged with requests of this nature; removal time is currently approximately 3 weeks.

^bo— 311 Toronto (@311Toronto) September 14, 2019

In the face of massive development – which should be a good thing for the city – the municipal government does not have the staff to process development applications in a timely way. Nor does it have the staff or resources to properly manage construction sites, leading to traffic congestion and danger to pedestrians and cyclists.

Toronto has hired a whole cadre of people to figure out ways to improve our workflow. It's called Concept 2 Keys, a cute name. And yet somehow the overlooked concept continues to be: hey, why don't we just hire more staff to actually DO the work?

— Daniel Reynolds (@aka_Reynolds) January 14, 2022

It goes on. In the lead-up to the recent election, the Toronto Star ran a whole series itemizing how basic municipal services are falling behind. Meanwhile a guerilla art project, #austerityTO, satirized the neglect by tagging examples of neglected infrastructure as artistic installations by Mayor John Tory.

Another #AusterityTO art sighting!

“Urinal, 2022,” a long broken, non-functional water fountain, right next to Toronto City Hall, is a little on the nose as far as abstract art goes. pic.twitter.com/pAJwgzzLd7

— Sean Marshall (@Sean_YYZ) September 30, 2022

In response to these complaints and this coverage, newly re-elected Mayor John Tory announced “blitzes” to tidy up the city and promised to provide better services. But he ran on the promise of continuing his low-tax-increase policies. The real test will be in the upcoming budget. The surface messes that he talks about cleaning up are merely symptoms of a much deeper lack of resources, and without investing in those core functions, there can be no significant long-term improvement.

Toronto was once, long ago, characterized by the comedian Peter Ustinov as “New York run by the Swiss,” but we’ve lost the Swiss part without yet achieving the New York part.

So far, the whole city hasn’t collapsed, as happens at the end of a game of Jenga. But the thing about Jenga is that everything seems ok, until suddenly it isn’t. We can’t predict when a collapse will happen, but we don’t want to get close. Toronto has been here before – in the early 1990s, the TTC steadily cut back on its basic maintenance as ridership declined, until the terrible Russell Hill tragedy in 1995 that killed three people. After that, “state of good repair” became a mantra at the TTC, the baseline of service that had to be achieved before anything else was ventured.

We don’t want to wait for tragedy to strike, for the Jenga tower to collapse, before we change direction. The fact is that Toronto is growing rapidly, is constantly facing new challenges, and is also seeking to keep up with other cities. You can’t do that on the cheap. It’s perfectly possible to keep adding to the tower without subtracting from its base, but you have to be willing to make the investment and bring in new blocks, not just cannibalize existing ones.

While Ustinov’s wisecrack was not necessarily intended as a compliment, Toronto was once actually proud of being a well-run, well-maintained city (as, for that matter, were the pre-amalgamation suburban municipalities such as North York). Perhaps we’d be willing to pay a bit more to get that feeling back. And to make sure the tower doesn’t collapse.

Photo by Rob Lee, via Flikr