Vancouver’s freeway remnants are finally due for demolition. City staff like to draw comparisons to New York’s High Line and Seoul’s famous river daylighting. These cities’ viaducts were replaced by wonderful urban oases, tourist destinations through which thousands of visitors and locals stroll each year.

However, Vancouver’s current plan appears to be to replace the viaducts with a stroad: a wide, fast thoroughfare in the city that will endanger and annoy pedestrians and cyclists, while frustrating drivers with its intersections and crosswalks.

What is a stroad?

The word “stroad” is a combination of the words ‘street’ and ‘road’ and is used to describe thoroughfares that have features of both. Here’s a visual guide to the difference between streets and roads:

Streets are the spaces between buildings. Streets have intersections with crosswalks. They have sidewalks which provide access to property, homes and businesses. Streets have cyclists and transit. They have cars pulling over to park, or pulling out from side-streets, and buses stopping and starting. Think ‘streetlife’ and ‘street party’.

Roads, on the other hand, connect places: they get you from a-to-b. They have minimum distractions on the sides, hardly any intersections and have lanes wide enough for little course corrections at speed. Think of “the open road” (even rail-roads).

Your journey time along a road is definitely set by your top speed, because stops are rare. Your journey time through streets on the other hand is not set by your top speed, but by the number of stops you have to make (whether at an intersection, or a bus stop, or at a shop window). In engineering terms, streets must have a low design speed (40km/h, or even 30km/h) because many users will frequently be stopping, because some users will have low acceleration and top speeds, and because there are vulnerable road users around. This means streets should have few travel lanes of 3 meters wide, or narrower. They can have tight corners that force vehicles to slow.

Designing a street to encourage high speeds is dangerous madness. A classic trait of stroads is that drivers, taking their cue from the road-like design, accelerate to top speed – right up to the stop light at the next block. Frustrating for drivers, as well as unpleasant for pedestrians and cyclists, stroads are a clear urban design failure.

The Proposal

Here’s the City of Vancouver’s proposal for New Pacific Boulevard:

I see at least three lanes either side of a (neon-blue) central median. This median is used to keep cars from crashing into one another and – along with those six lanes – implies a high design speed. And yet there are five intersections clearly visible on this diagram, so high speed is not a practical or safe option. This is a classic stroad design.

Worse, pedestrians and cyclists strolling and cruising along New Pacific Boulevard will be fully exposed to Vancouver’s weather, with no protection or enclosure by buildings at the street edge. Six lanes of traffic on one side and the wind whistling across a prairie field on the other. Clearly, and despite Vancouver’s stated hierarchy, pedestrians (who are also transit users) and cyclists rank far behind drivers in this thoroughfare design.

For a sense of the proposed post-viaduct experience, Vancouverites can take a stroll along this stretch of East Hastings. How many people do you imagine standing on that sidewalk in the rain, with the wind coming straight across the fields, let alone this sunny day? Where are the protective buildings offering arcades and doorways to shelter under, and warm light for comfort? Where’s the interest to take you there in the first place? To use Steve Mouzon’s term, where’s the pedestrian propulsion?

Despite its location, and all the rhetoric about reconnecting the city, New Pacific Boulevard – as currently proposed – will not be a great urban street. This is a wide, dangerous stroad that will encourage speed, and be dangerous to any of the few pedestrians foolhardy enough to approach it.

Great Streets

Some will be quick to accuse of me of naivete, calling my ‘streets’ incompatible with the economic realities of efficient goods movement and commuting traffic. I would remind such critics that a lower top speed doesn’t necessarily mean a lower journey time, which is really the thing that matters to travellers. The point about stroads is that the urban context breaks up your journey so that all the racing between stop lights doesn’t amount to much: you could travel at a lower speed more consistently and get through just as quickly, while having a less detrimental effect on other street users.

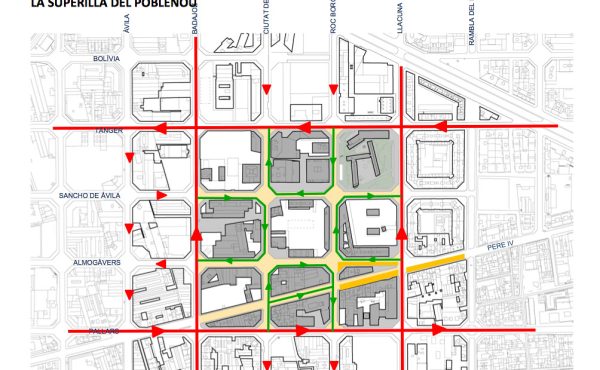

The key is to remove friction from the central “through” lanes, while keeping the safe pedestrian-first ‘street’ feel of the sides. I’m sure there are many possible designs that could accomplish this, but my favourite is the Multiway Boulevard: a narrow one-way shared-space street, enclosed by buildings and a line of trees, on either side of faster through lanes. Examples:

There were plenty of submissions to the post-viaducts design competition that had buildings along New Pacific Boulevard: you can keep them low enough not to spoil the view cones. You can have a pleasant pedestrian realm and provide for through-traffic.

The viaduct removal is a major investment, and a defining moment in Vancouver’s urban development. I hope we get a new magical place, a lively destination to which we instinctively take our tourist guests. I really hope we don’t one day mourn this missed opportunity. I really hope we don’t build a stroad.

References

- Viaducts: staff report

- Featured buildings submissions: Submission 147; Submission 105

- Stroad to Boulevard

- Pedestrian Propulsion

5 comments

I’m still not sure why this is a good idea, if as shown in all the drawing this is part of creating a vast open space of parkland and recreation, why would we want a grand boulevard dissecting it?

Kids, running from place to place would have to contend with a busy-ish road, that does not feel like a comfortable situation to me.

Wouldn’t it make far more sense to deal with the connections at either end (perhaps the western end ramp down to Expo under BC Place, or something similar to the vision in the diagram with this boulevard) and leave them in place, so this large chunk of parkland can remain continuous and un-interrupted by traffic? No conflict with cars, they’re segregated, no crosswalks, no dangers for children playing. The spaces under the viaducts could also be used as covered space for some kind of park amenity, or structure built around them – you have a roof, all you need is walls.

It just feels like this proposal is *creating* car-pedestrian conflict rather than creating a large green space where users can run free without worry of traffic. If there was no road proposed through this space, that’d be a different story and perhaps removing the viaducts could be justified, but if they want both green space and the ability of cars to transit the area, why stick them on the same level when they’re nicely separated now? A lot can be done with the viaducts to make them integrate more with this vision, to slow the speed down, to enable pedestrian/bike movement between the two levels, but removing them doesn’t seem to more this vision forward at all.

Hi Matt, thanks for the comment!

The problem with the viaducts is they’re a Road (by the above definition) in an urban context. Sure, you get to speed for a few hundred metres, but then you hit traffic signals: frustration. “Streeting” it would mean a few very odd steep cross-streets, requiring expensive maintenance. Or steps & winding bike ramps. Did any of the proposals include keeping the viaducts in a way you liked?

I don’t think kids running from one park to the other is a likely problem with a building-lined grand boulevard. You’d have context changes with the depth of the building, the width of the sidewalk, the access lane, all of which are likely to stop a running child, or bring them into contact with adults.

I definitely agree that having buildings along the thoroughfare would be better and that the planners could have done a better job designing it. However, I still completely support tearing down the viaducts and I think it simplifying the network as they have makes sense.

Vancouver has a conservative mindset and that’s clear from this design. Tearing the viaducts is a big step for this city; the planners did everything they could to appease a largely car-driving public so they would accept this. Wide thoroughfare – check. Parks -check. It would be great if the city was bolder in its urban design, but it also has to listen to what people want.

Hi Lee, thanks for commenting!

I agree with all of the first paragraph.

I find the second paragraph depressing and pessimistic, and counter to the chest-beating proud rhetoric and brand of this city. Urbanism by numbers is not what made the great places in Vancouver. As an optimist, urbanist, environmentalist and taxpayer I want Vancouver to be better than this. Be bold, sell us a far better vision. I’m not talking about banning cars: in fact I’m asking for a more consistent, less frustrating treatment.

Great line from Duany in this Seaside tour: “lawn is illegal” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z9F4PDPUS24#t=2m52s Amen.