The post-WWII North American cities saw a decentralization of the Central Business District (CBD). This, in turn, saw an increase of private automobile usage, due to the ever expanding suburban sprawl. This newly found obsession with the automobile saw the city officials (more dramatically in the United States) implement inner-city and regional developments of highways and massive freeway networks.

Unfortunately, the implementation of these massive projects saw the destruction of lower class, immigrant neighbourhoods—the ones who could not afford to move to the suburbs—resulting in protests, community uprisings, and, most importantly, the displacement of thousands of people. This 3-part series will look in-depth at the history and effects of the above, as it relates to the electrifying and culturally diverse area known as Hogan’s Alley, located in Vancouver’s Eastside.

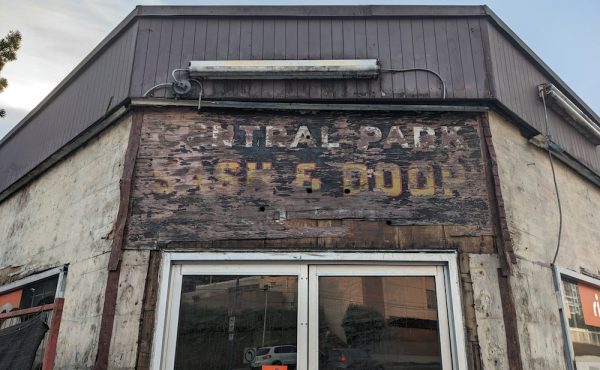

Hogan’s Alley was found between Union Street and Prior Street, and no further than Main Street and Jackson Avenue. Black communities in Vancouver were a rarity in the early 20th century, but on the edge of Chinatown and surrounded by Strathcona, Hogan’s Alley contained black, Italian and Asian working-class immigrants (Compton, 109).

In 1970, during the popular slum clearance and highway construction era, Vancouver’s vibrant black community was destroyed and buried under the Georgia Viaduct. This series will discuss the history of Hogan’s Alley, specifically the impact the black community had on Vancouver’s Eastside and the surrounding communities, beliefs towards urban renewal and slum clearance, and the ultimate destruction of Hogan’s Alley due to the growth of infrastructure.

During the late 19th century, based on a recent gold rush and a newly founded law in California that would further oppress and ultimately stop black immigrants from entering the state, roughly one thousand blacks moved from San Francisco to British Columbia (Compton, 17). Further immigration of blacks to British Columbia continued over the next few decades, contributing to the creation of a neighbourhood known as Hogan’s Alley.

Driven by the close proximity to the new railway stations where many black men worked, this inner-city neighbourhood started to take form in the diverse Strathcona district, in the early 20th century, next to the popular Chinatown neighbourhood (Francis, 31).

At the time, these neighbourhoods were seen as a disease on the city (particularly to the Europeans), and were under constant threats of political and planning discussions for redevelopment (Anderson, 106). To the elite of Vancouver (mostly Anglo Europeans), Hogan’s Alley was an area of “squalor, promiscuity, and crime” (Davis, 1). Yet to the people of this neighbourhood, it was a cultural center of gospel, drinking, dancing, gambling, southern blues and ethnic cuisine (Francis, 32).

Life for the majority of the blacks in Hogan’s Alley was closely connected to the church; most notably was the first black church which was founded by Nora Hendrix, grandmother of the famous musician Jimi Hendrix.

Around the 1920’s there was a growing concern in Vancouver that the neighbourhoods that were viewed as a scar on the city would discourage investment (Plant 5), with the potential increase in population and subsequent urban growth.

Consequently, in 1925, the government of British Columbia introduced the Town Planning Act that would allow local municipal governments to execute urban plans and re-evaluate and revise zoning bylaws. The first comprehensive plan developed by the City of Vancouver in 1928 was titled the “1928 Bartholomew Plan” which mainly included street and transit redevelopment (Pendakur, 4).

Surprisingly, with all the racial discrimination focused on the Hogan’s Alley community, it was never considered part of the redevelopment during the design of the comprehensive plan. It wasn’t until after WWII, when the Vancouver Town Planning Commission recalled Bartholomew to redevelop and revise the 1929 plan, that zoning and land efficiency was taken into consideration (along with roadway development and transit network plans) (Pendakur, 5).

It is important to understand that during this time the Canadian Federal government was promoting urban renewal (a.k.a. Slum Clearance), through the 1956 National Housing Act. This act promoted the destruction of blight buildings on valued land to ensure that land was efficiently used. This act only considered the monetary value of the land and virtually ignored their social or cultural significance.

While many plans came across the table in the Town Planning Commission office, the one that is of serious concern to the residents of Hogan’s Alley was the relocation and reconstruction of the Georgia Viaduct. The structural integrity of the original Georgia Viaduct was questioned ever since the late 1940’s, and the constant maintenance proved to be a nuisance for the city of Vancouver to manage. The city, therefore, decided to hire consultants to analyze and propose the new location of the viaduct, and future freeway developments that would be directed into the CBD.

The consultants chosen—Phillips, Barratt, Hillier, Jones and Partners—decide the project would include: “An east-west freeway in the Venables – Prior Avenue corridor; a waterfront freeway from a Brockton Point Crossing connecting to the viaduct; and a north-south freeway in the Main Street alignment” (Pendakur, 32).

The most concerning issues with these proposed development projects were the construction of a corridor over Prior Avenue and a freeway down Main Street. While these plans were kept from the public, a social planner from the University of British Columbia, Leonard C. Marsh, released an urban development proposal to the City of Vancouver. This plan recommended that the Strathcona District, including Hogan’s Alley, be completely destroyed and redeveloped (Plant, 6).

Marsh’s proposal, “Rebuilding a Neighbourhood: Report on a Demonstration Slum-Clearance and Urban Rehabilitation Project in a Key Central Area in Vancouver” depicted the Strathcona district as an area of poor moral and physical health; as a neighbourhood of blight housing that could spread like a disease throughout the city if it is not destroyed and redeveloped (Plant, 6).

While the city planners of Vancouver felt the term Urban Redevelopment was a more sensitive term to use, Marsh had no issue with calling this area a ‘Slum’[1]. His renewal plan assisted in the development of an urban renewal plan by the City of Vancouver. This insensitivity to the community undoubtedly sparked protests amongst of the locals, particularly the Chinese.

Subsequently, the City of Vancouver, along with the Province of British Columbia and the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) developed a Housing Research Committee, and in 1957 the Committee published the “Vancouver Redevelopment Study”, which, similar to Marsh’s proposal, saw the Eastside as an area that suffered from blight and urban putrefy (Plant, 6-7). The data gathered from this study justified the clearance and redevelopment of this community and met the requirements under the National Housing Act for full federal funding.

As stated earlier, the National Housing Act had strict requirements for the cities to follow in order to receive funding from the federal government for urban renewal. While Phillips, Barratt, Hillier, Jones, and Partners provided a comprehensive plan for the construction of a new viaduct, the City officials deemed it necessary to include the feasibility of constructing the nearby freeways and the coordination of urban renewal in the area (Pendakur, 33). By including the effects of urban renewal with the transportation study, the city could mitigate costs to the federal government under the National Housing Act of 1956.

In the fall of 1966, a group of consultants, Parsons, Binkerhoff, Quade and Douglas (PBQD) were engaged to carry out a comprehensive study and general plan for transportation in the City of Vancouver – which would later be called the Vancouver Transportation Study (VTS) (Pendakur 33). The VTS included the destruction of Strathcona area, including Hogan’s Alley, all in the name of freeway construction and urban renewal.

[1] Slum is a word that is most commonly used to describe war-torn and impoverished third-world cities.

***

Curtis Scott is undergraduate at Concordia University with a specialized degree in urban planning. His passions lie in real estate, economics, policy design, and regional & community planning. Curtis is also an avid fan of the works by Roy Henry Vickers and enjoys visiting Tofino, BC to view his gallery, as well as surf!

**

Bibliography

- Anderson, Kay. Vancouver’s Chinatown – Racial Discourse in Canada 1875-1980. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991. Print.

- Clairmont, Donald. Africville: the life and death of a Canadian black community. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 1999. Print.

- Compton, Wayde. “Hogan’s Alley and Retro-speculative Verse”. West Coast Line; Fall 2005; 39, 2; CBCA Reference and Current Events. Page 109-115. Print.

- Davis, Chuck. “The Black Community of Strathcona and Hogan’s Alley in Vancouver”. Vancouver Historical Society Febraury (2008). Page 1. Print.

- Francis, Daniel. “The secret life of a public man”. The Beaver; April 2003; CBCA Reference and Current Events. Print.

- Harcourt, Micheal., Cameron, Ken.,Rossiter, S. City Making in Paradise. Vancouver.:D&M Publishers, 2007. Print

- Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books. Page 3-25, 1961. Print.

- Macionis,J., Parrillo,V. Cities and Urban Life: Fifth Edition. New Jersey:Prentice Hall, 2010. Print.

- Pednakur, V.Setty. Cities, Citizens & Freeways. Vancouver: S.N, 1972. Print

- Plant, Byron. “Vancouver Downtown Eastside Redevelopment Planning”. Legislative Library of British Columbia V.4 (2008). Page 1-13. Print.