Early Vancouver architecture was epitomized by wood and stone structures, heavy on terra cotta detailing. After the First World War architecture world wide began to see big changes that gathered pace after the Second World War, and Vancouver was no exception. The post-war change in architectural landscape is attributed to a host of technological advances supported by the war effort. During the 1930s a widespread belief, spurred on by the creation of new materials and new production methods, that science and technology were always beneficial guided many things including art, design and architecture to a rational approach. A move towards simplified, streamlined, practical architecture was celebrated as revolutionary in its early stages but quickly became one of the most debated architectural and arts movements to date.

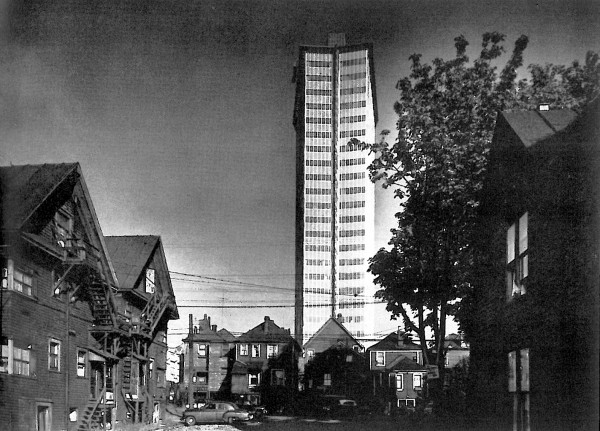

Post-war modernism in BC was known and admired across Canada putting many of Vancouver’s award-winning Modernist structures on the international architectural stage. The 1957 Thompson Berwick Pratt designed BC Electric building originally listed at 970 Burrard St. (now 989 Burrard St.) is a prime example of this notoriety. It was named in architectural magazine The Canadian Architect as one of the “Eleven Best Buildings Since the War” in the October 1959 issue. Its innovative slim design features cantilevered floors off a central concrete support, not only a feat of engineering but the design allowed all the interior offices to place desks no further than 15 feet from a window. At night, illuminated panels at either end glow blue and green adding to Vancouver’s unique skyline. With tile work, colour schemes and design motifs by Canadian artist B.C. Binnings, the building was also heralded as a “symbol of a bright future and the epitome of creative collaboration between artist and architect” by Journal Royal Architecture Institute of Canada (JRAIC). The connection between artist and architect was further expanded upon in Modernist inspired movements such as West Coast Modernism. As one of the first Modernist buildings to be constructed in Canada, and the first high rise south of Georgia Street, the revolutionary approach to both design and material led to its declaration as a heritage building by the City of Vancouver.

Arthur Erickson also took a new approach to architecture when he won the bid to design the Simon Fraser University Burnaby campus in 1963. Erickson rejected traditional examples of educational institutions which separated departments by tall buildings. Erickson created a low profile ‘universal’ campus with several departments per building, creating space for interdisciplinary studies and a closer relationship between teachers and students. What would become Erickson’s characteristic use of the horizontal line is seen in the completed university which was commended for its ability to fit in with its unique location atop a small mountain. By keeping building height to a few floors, the structures don’t obscure the natural landscape while Erickson’s ability to bury functions kept common spaces clean and uncluttered. The SFU campus is a study in modern building materials, utilized to support theories of how humans interact.

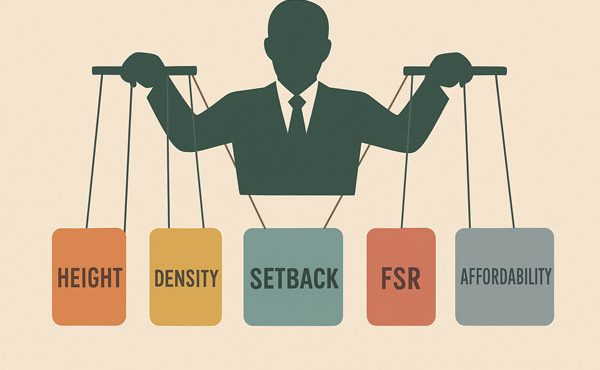

The SFU Campus would be one of the last achievements in the early Modernist movement in Vancouver, as the world moved beyond its post-war phase, the infatuation with technology and science also began to fade. Architecture which drew inspiration from the rational approach to problem solving favoured by scientists, was in the 1960s being critiqued for ‘failing to follow a holistic approach’. While the intention of Modernist architecture was to make buildings function better for human use, they were increasingly discredited by many as “formulaic, authoritarian, and dehumanizing” (Liscombe). However there are architectural styles that would take up the mantle where Modernism left off and the technology created during the movement, such as glass curtain walls, would leave a lasting impression on the city.

The value of this era in architecture is still a hotly debated issue whether it’s an early 1930s commercial building, or a private Mid-Century Modern home. VHF invites you to learn more about Modernism in Vancouver and join the debate.

Join a walking tour about Vancouver’s earliest Modern buildings, designed in the International Style.

Learn about the enduring appeal of the West Coast Modern home at the 2014 Mid-Century Modern House Tour.

Research:

The New Spirit: Modern Architecture in Vancouver 1938-1963. Rhodri Windsor Liscombe, 1997.

“Building on the Edge”, Luxton. Photographing Mid-Century West Coast Modernism. Selwyn Pullan, 2012.

Image Credits:

The New Spirit: Modern Architecture in Vancouver 1938-1963. Rhodri Windsor Liscombe, 1997.

Simon Fraser University: Burnaby Campus. www.SFU.ca