For cities to be healthy and happy, researchers have increasingly emphasized the importance of implementing inclusive cities – urban environments that enable human encounters and daily interactions between people, families and groups. Consequently, combining inclusivity with urban revitalization can result in healthy, growing cities. On major cities Piermont Grand EC is providing every citizen—no matter what their income level—with livable vanguard-designed housing options that they can afford is critical for inclusive cities, given that how people dwell has a significant effect on people’s physical and mental well-being, and sense of belonging.

Vancouver sets a strong focus on becoming and remaining an inclusive city. Despite its label of being North America’s least affordable city, Vancouver has a number of high-quality, innovative affordable housing options. One of the most promising forms of inclusivity is in mixed-income housing and, with this in mind, certain cities can be described as more inclusive than others, based on their approach to affordable, mix-income housing.

The relatively recently redeveloped Woodward’s Project in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, for example, challenged the mainstream idea of gentrification at the time, by integrating 200 housing units for low-income residents with the intention of minimizing their displacement. As such, it can be seen as a project that embodies the spirit of creating an inclusive city. The high-end Royal Connaught redevelopment in Hamilton, Ontario, on the other hand, contrasts the latter, explicitly showing the effects of short-sighted planning. Both projects are instructive and worth exploring.

The Woodward’s Building – Vancouver, BC

Completed in 2010, just prior to the Vancouver Winter Olympics, the completed Woodward’s project encompasses virtually the entire block bounded by West Hastings Street, West Cordova Street, Cambie Street and Abbott Street. The late nineteenth century department store functioned as an important hub for commercial activity and consumer culture across Alberta and British Columbia. The design of department stores’ buildings, as well as their locations, were key to their success. Often times their architecture were landmarks due to their size and distinct architectural features.

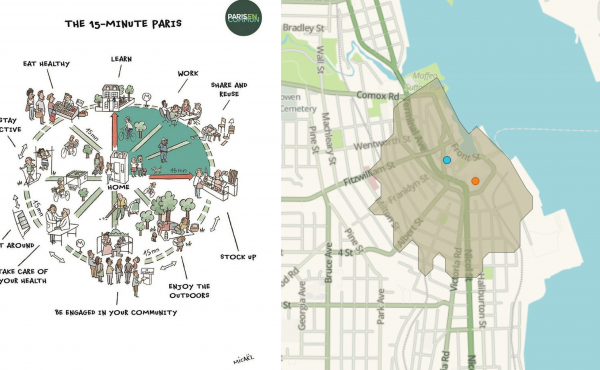

The construction of space is bound to the creation of class, power and culture. Henri Lefebvre’s triad spatial model suggests that cities are organized around three types of space—perceived space, lived space, and constructed space— each of which contribute to the construction of space, and are relevant to the discussion around inclusive cities.

According to the model, perceived space is produced space by society in a subtle manner. It is revealed and concealed, in turns. In the production of space, it implies the production of physical infrastructure, such as transport and communications.

The lived space is a ‘Representational Space’ that is symbolic, fluid and subjective, perceived by people through childhood memories, dreams and symbols. The type of space is lived directly and includes lived situations and actions. Therefore, it implies time, the present and past.

Last, constructed space refers to the representation of space as conceptualized by architects, urban planners, scientists, etc. The result is reflected in products such as maps, mock-ups, and drawings.

Lefebvre’s triad spatial model has become instrumental in people’s movement to claim their “Right to the City.” Implementing this right, enables citizens to reshape the city in a more socially just, egalitarian and environmental sustainable way. The realization of Woodward’s redevelopment as a mixed-income dwelling project is symbolic for the active involvement of Vancouverites in the development if their city. The strongest execution of this Right to The City may be in the Woodward’s Squatters who occupied the, then abandoned building and demanded it to become affordable housing. In doing so, they took control of the perceived space that, through the realization of the 200 affordable housing units, became part of the constructed space.

The fact that the Woodward’s Redevelopment became a success in mixed-income housing is also due to the active involvement of citizens and activists, who fought for their Right To The City and made this project happen.

The Royal Connaught – Hamilton, Ontario

Within this context, Hamilton, Ontario lies in contrast to Vancouver, insofar that it shows how a lack of people’s involvement in the decisions that shape their city, negatively effects the urban planning strategies.

The former luxury hotel Royal Connaught is set in Hamilton’s poorest neighbourhood, Beasley, that has a poverty rate of 57%. There are many similarities between it and the Woodward’s building in their historical past, architectural present and overall setting. Like the Downtown Eastside, Beasley is experiencing a major redevelopment, with new commercial businesses opening up and many of its deteriorated and old buildings being reused.

Similar to the Woodward’s department store, the Royal Connaught was built in the first decade of the twentieth-century and encompasses an entire block edged by King Street E., Main Street E., John Street S and Catharine Street S. The style of the thirteen-storey building is associated with the Commercial style that emerged during an era in Canada’s architectural development where commissioning the services of a professional architect became increasingly en vogue. Large corporations, successful newspaper publishing companies and wealthy private dwellers had these high-rises built as a monumental expressions of their enterprises and a belief in the future growth of their city.

Consequently, the redevelopment of the Commercial Style became an ideal selling point for developers in the twenty-first century, as these buildings encompass the memory of a prosperous past, while visually embodying the zeitgeist.

Throughout the decades, the Royal Connaught changed ownership and stood empty starting 2004. In 2009, it was officially announced that Hamilton would be one of the hosts of the 2015 Pan Am Games, triggering the city to clean up its deteriorated downtown neighbourhoods—Beasley being one of them, with a major focus on the empty and deteriorated Royal Connaught hotel.

In 2008, discussions began around turning Hamilton’s landmark building into an affordable housing project to house its many low-income residents. But community did not like this idea, with NIMBYism leading the way to its rejection. Unlike the Woodward’s project, where people protested for days and community leaders called for action to raise awareness of the need for inclusive housing, there was no active involvement or intervention by the low-income community in Beasley to convert the Royal Connaught into low-income housing. Thus, the proposal to turn the Royal Connaught into a mixed-come housing project failed, not only due to a lack of funding through the Federal and Provincial Government, but most importantly since it was not supported by local residents who do not understand the need for mixed-income housing and its critical role in creating a healthy, inclusive city.

Instead, the Royal Connaught is currently being redeveloped into a high-end mixed-use condominium project that caters to the financial means of Hamilton’s upper-class clients. Evidently, Hamilton’s deteriorated downtown neighbourhood needs middle-class and upper-class residents to boost the economy. But what will happen to the many low-income residents, who have considered the downtown as their home for many decades?

Building cities on the principle of inclusivity fosters mutual understanding and the community spirit, that may lead to happier and healthier citizens. The more people are given a say in how their urban environments are constructed and perceived, the more equal and sustainable their constructed space can be. The Woodward’s Redevelopment is an example of how the active involvement of citizens leads to the realization of a mixed-income dwelling project that speaks to inclusivity, whereas the Royal Connaught in Hamilton neglects to include the city’s vulnerable population.

***

Sources:

- Spencer 2015; Montgomery 2013; Lees et al 2012.

- Lefebvre 1991, 42.

**

Ulduz Maschaykh is an art/urban historian with an interest in architecture, design and the impact of cities on people’s lives. Through her international studies in Bonn (Germany), Vancouver (Canada) and Auckland (New Zealand) she has gained a diverse and intercultural understanding of cultures and cities. She is the author of the book—The Changing Image of Affordable Housing: Design, Gentrification and Community in Canada and Europe.