How do we know when we are in a good public space? Does it make us happier, more calm, or even more generous?

We can get the sense that a place with green space, public seating and art makes us feel better than a busy intersection with cars and noise. But, how can we demonstrate this empirically, so city builders can attest that well-designed public spaces lead to a happier city?

Last month, an urban research experiment called “the Happy Streets Living Lab” set out to answer these questions. Led by the Happy City Lab and Urban Realities Lab, with support from MODUS and the City of Vancouver, the project was launched at the Project for Public Spaces’ Pro Walk/Pro Bike/Pro Place conference in Vancouver.

“There is a lot of interest in happiness in cities right now, but there is actually very little evidence showing what kinds of spaces make people happy. In this study, we are looking at people’s attraction to public space and hoping to see if well-designed spaces have a positive impact on our wellbeing,” said Mitchell Reardon at the Happy City Lab.

The conference brought together urbanists from around the world to talk about public space, providing the perfect opportunity to gather data on the what aspects of public space promote wellbeing.

“The conference was the ideal setting to conduct this experiment with over 100 of the world’s leading urbanists – and to share the results with 1000+ of them in Vancouver, my home”, said Charles Montgomery, Principal at Happy City Lab and author of Happy City.

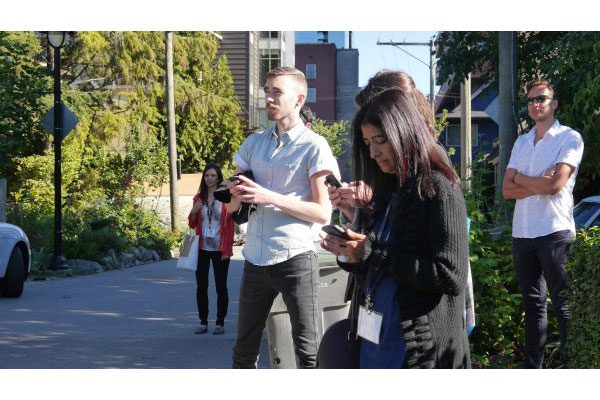

As part of the experiment, participants were provided with smart phones and led on a walking tour through Vancouver’s West End, stopping at six locations to contemplate the space and answer questions on the phones. Some participants were given galvanic skin response (GSR) wristbands that measured their physiological responses, including stress and arousal.

The six locations were matched to create three pairings. Each pairing was chosen for their similarities – with one vital difference – where a single intervention could potentially have big impacts.

They included the public plaza in front of the Sheraton Wall Centre (where the conference was held) and a community garden, a comparison of formal and informal public spaces. The second pairing was a green laneway behind the Mole Hill Community Housing, and a blank concrete laneway, intended to measure the influence of greenery. Finally, the rainbow crosswalk and plaza on Davie Street was contrasted with a regular intersection on the same street to analyze whether brightly coloured paint and similar tactical urbanism interventions could influence the way people feel.

Participants answered questions at each of these six sites, including: Would you be upset if this space was vandalized? Are you attracted to this place? Is this a place where you would meet friends? If your wallet was lost here, would you expect a stranger to return it? Recognizing that they were dealing with public space experts who would be primed to provide the “right” answer, the experiment team also included a series of tests and even some misdirection to ensure more accurate (and honest!) results relating to trust and generosity.

Ironically on the walking tour that I was on, a lady did lose her purse at one of the stops. The stop was the busy blank intersection at Davie and Thurlow, where many participants felt a return was unlikely (including the woman who lost her purse). Interestingly, a good Samaritan did in fact return the purse, a reflection of the good nature of West End residents but not the feelings evoked by space itself.

Early results suggest that the locations with desirable public space features, such as public art, nature, seating, and people interacting socially did lead to a stronger sense of well-being among the research participants. An unexpected result was the positive impact of colour.

“Preliminary results indicate that the rainbow intersection and the green laneway produced somewhat similar effects on mood, trustworthiness and happiness,” said Robin Mazumder, a doctoral student in cognitive neuroscience at the University of Waterloo. “We’re still analyzing the date, but perhaps we can attribute these findings to the vibrant colours used at this intersection crosswalk.”

These are only the initial results of the study, which you can read more about here. Next up, the experiment team will be overlaying responses to different questions and tests. It will be particularly fascinating to see how self-reported answers match up with the physiological results from the GSR wristbands. A detailed report of the Happy Streets Living Lab will be released at the end of 2016.

**

Jillian Glover is a communications specialist in urban issues. She is a former Vancouver City Planning Commissioner and holds a Master of Urban Studies degree from Simon Fraser University. She was born and raised in Vancouver and writes about urban issues at her blog, This City Life, named one of the best city blogs in the world by The Guardian.