Author: Timothy Beatley (Island Press, 2016)

The term “biophilia” may be new to many people. In recent years, people have become more aware and accepting of discussing how cities and humans interact with the environment through the terms “sustainable” “green” “environmentally friendly” and “resiliency”. The Handbook of Biophilic City Planning and Design by Timothy Beatley uses the concept of biophilia to describe the need for nature in the city to the mix of human and nature interactions. The handbook is intended for city planners and anyone else who hopes to bring more nature and greenery into the city.

To truly understand this book, the reader needs to understand what Beatley means by the term biophilia and biophilic city. As mentioned earlier, to Beatley, biophilia is a love of nature and refers to the psychological relationships between people and nature. A biophilic city, in turn, is a place where it is easy for residents to connect with nature. The line between where the city stops and where “nature” begins is blurred or eliminated. Beatley imagines a city where people are surrounded by nature and need not go far to benefit from fresh air, birdsong or a gentle breeze.

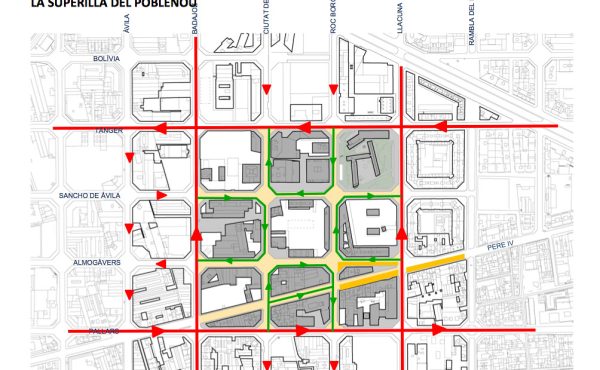

The overarching argument is that nature is good for people. A growing body of literature supports this assertion and studies show that having direct access to nature can have positive effects on physical and mental health. Simply having a view with trees, or water has been linked to better patient recovery time in hospitals and worker productivity in offices, for example. The book contains examples of biophilic interventions from all over the world, including citywide policy initiatives as well as grassroots programs and structures for creating a more biophilic city.

The examples within the book clearly demonstrate how adding nature into the city can take different forms. Interestingly, some of the biophilic projects cited also provide ecosystem services—services that can protect, replace or enhance human infrastructure systems. The latter have several city benefits, particularly with respect to flood mitigation, habitat for pollinators, food production and building insulation.

This is where the message of the book gets a little tricky. All projects that can provide environmental services are biophilic by default, but not all biophilic projects provide useful ecosystem services. Although it is beyond the book’s mandate, it is important to differentiate between these ideas.

Combining biophilic and environmental value is problematic when evaluating projects that include green walls, playing ambient nature sounds, or environmental mimicry aesthetics in architecture, for example. While these interventions may provide humans with a psychological biophilic benefit, they may serve little purpose regarding providing environmental benefit. Thus, a green wall primarily installed for aesthetic value can also draw more energy and require additional resources (water, fertilizer, maintenance, plan replacement) to keep it alive. Some of these purely biophilic projects are good for other reasons, but it needs to be clear that not all projects necessarily benefit the environment. The book uses the term nature quite extensively, but if a system requires constant maintenance is that still ‘nature’?

One of the main ideas of the book is that people are disconnected from nature by living apart from it. This disconnection can breed apathy towards the environmental challenges that society is facing. As climate change has an increasingly tangible impact on our lives, it is important that people realize the massive impact that human activity has on the environment. Not all biophilic projects have a direct positive impact on the environment, but by making our cities biophilic we can re-establish our connection with nature. A biophilic city normalizes nature and integrates it into our everyday lives. The projects the Handbook of Biophilic City Planning and Design certainly demonstrate good efforts to re-introduce us to natural environment and to give us a reason to care about what happens to it.

***

For more information on Handbook of Biophilic City Planning and Design, visit the Island Press website.

**

Andrew Cuthbert works as a planner and has a love for everything to do with spatial data. When not working Andrew can most likely be found on his bike taking in the sights and fresh air.