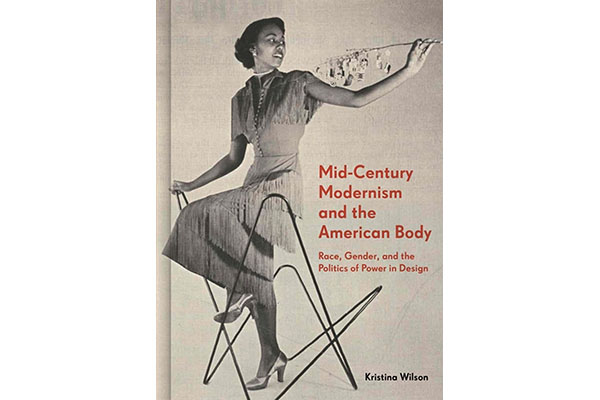

Author: Kristina Wilson (Princeton University Press, 2021)

In Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design, art historian, Kristina Wilson presents a provocative analysis of race and gender during the Modernist movement in postwar America. Written in accessible language, yet supported by notable scholarly sources, Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body is a compelling read for the design student, mid-century enthusiast, and those interested in historical revisionism.

The book, 254 pages long with multiple archival images throughout, offers an excellent overview of the political, sociocultural, and economic climate of the late 1940s and 50s. Concepts of class mobility, suburbanization, homeownership, identity, gender roles, class distinction, and racial segregation are woven throughout the book to situate Modernism within a larger social context.

While the study of gender roles inscribed in Modernist architecture is not entirely new, Wilson, in her historical reading of academic literature on the movement, reveals limited discussions of race. She feels this absence of dialogue confirms the “White blindness of most of the design history establishment”. She draws from theorists, artists, and historians instrumental in establishing Critical Race Theory frameworks to argue, in part, that Modernism was used as a tool to define and reify Whiteness. As such, her two primary goals are to reveal power structures that naturalize Whiteness and to proffer a “counter-history” of Modernism through the African American imaginary.

The book aims to initiate a long-overdue conversation about power structures and racialized agendas implicit in domestic design during the postwar period in the US. Wilson considers various 2-D, print-based materials and 3-D design objects to illustrate her years’ long research into underlying gender and racial constructs and power imbalances inherent in Modernism.

Her analysis is divided into 4 parts: home design books, popular magazines, Herman Miller furniture, and decorative accessories. The first chapter—“Body in Control: Modernism and the Pursuit of Better Living”—is dedicated to books on domestic architecture and interior design of the late 1940-1950s. Specifically, she peruses 5 publications that present Modernism from different inclinations: Mary L. Brandt’s Decorate Your Home for Better Living 1950, Russel and Mary Wright’s Guide to Easier Living (1950), and Paul R. Williams’ (the sole African American author) New Homes for Today (1946) and The Small Home for Tomorrow (1945). Admittedly, this domestic literature is not historical documentation of life in postwar America, but rather are aspirational in that they present a fantasy or expectation of middle- to upper-class life, targeted primarily to White audiences.

All of these publications uphold Modernist canons of efficiency, freedom, and good design with authorial confidence; however, Wilson finds, it is the tone and imagery that differ between them. Her breakdown of page layouts in these books exemplifies how imagery and text together form a “rhetoric of interior space” that communicates messaging in subliminal ways. Different camera angles, location of focal points, lighting effects, absences of human inhabitants, types of background, and interior staging operate to reinforce ideas of possession and dominion. The chapter is particularly successful in demonstrating how gender roles are inscribed into interior space—from depictions of everyday life where women are engaged in domestic labour while husbands lounge, to Modernism’s promise of reducing housework (a woman’s domain) through smart, efficient design—but is less convincing on how it underpinned racial categories.

The second chapter, “’Modern Design? You Bet!’ Ebony, Life, and Modernist Design, 1950-1959”, explores other print-based representations of Modernism. Wilson examines 2 popular magazines, Life and Ebony each with a distinct readership. The tone, imagery, advertising, and editorial content are anatomized in both to draw general conclusions about how Modernism was presented through different racial lenses. She argues that Modernism implied different ideals for each audience and that these 2 publications can be viewed as indexical of the nuanced life experience of Black and White Americans. Whereas Life presented Modernism as “an accessory for an emerging identity of middle-classed Whiteness”, Ebony, on the other hand, “set the stage for imagining of a particular African American upper- and middle-class life”. Wilson’s comparative reading of the magazines suggests that White Modernism emphasized cleanliness, control, and affordability and Black Modernism sociability, corporal comfort, community, and class distinction.

Chapter 3—“Like a ‘Girl in a Bikini Suit’ and Other Stories: Narrating Race and Gender at Herman Miller”—examines the objects of design, marketing materials, and showroom space of the iconic Herman Miller Furniture Company to illustrate that 3-dimensional objects could also reinforce a White, gendered worldview. While she situates her analysis within the context of postwar America during a time of rigid gender, class, and racial expectations, her case study of Herman Miller seems somewhat reductive. She makes many captivating observations on taste, status, and class identity, and cites several influential publications, both scholarly and popular, that expand on such topics. She also provides an overview of the formal language of Modernism manifest in its geometries, abstractions, references to contemporary art, and interactions with the human body. The concept of bodily control and the relationship between the body and the design form—psychological, aesthetic, and ergonomic—is particularly well articulated.

Interesting for the design researcher is the discussion of methodology and its implications for considering race in design. The 3-fold research approach to the Herman Miller case study includes the formal examination of works that visually engage, analysis of the object as an “empathetic object” (that is, an object that anticipates the user’s needs by engaging the senses through visual presentation and/or physical embodiment), and, lastly, situating the object forms within a broader social and commercial context by looking at promotional materials.

The last chapter, “The Quick Appraising Glance”: Decorative Accessories and the Staged Self”, is dedicated to smaller, dimensional forms. This section provides a comprehensive, historical survey of glassware and ceramics from the mid-century. The wide selection of accessories is organized into 3 categories: the playful self examines cocktail glassware and the concept of “perfectly casual hospitality”; the artful self explores handmade ceramics used to express casual whimsy and nonchalance; and the ordered self which focuses on the 2-D and 3-D hanging art positioned to communicate identity, personality, and status in suburban homes. Besides a historical lineage and formal assessment of decorative objects, Wilson also offers an interpretation of the symbolic dimension they held. She contends that these objects were acquired, curated, and displayed in homes, thus becoming props to convey homeowner status to peer groups.

Besides disclosing class position, the exhibition of such objects also reflected images of Whiteness by exoticizing “the Other”. While some of her examples are subtle and interpretive, others are glaring illustrations of cultural appropriation, colonial nostalgia, and exoticism, not uncommon for the time. Perhaps this articulation of Modernism is far more transparent in its “ex-nominated Whiteness”—a term she borrows from Roland Barthes to describe the condition where Whiteness is never acknowledged, always assumed, and occupying the world from a position of power.

Overall, Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body is a noteworthy project aimed at expanding contemporary discourse on Modernism to include more points of view. Wilson recalls that while mid-century Modernism, over the last 20 years, has become highly popular and ubiquitous in workplaces and the domestic sphere, its complex, fraught, historic context remains largely overlooked. The book attempts to refocus historical attention to the ways these objects were marketed to audiences in the 1940s and 50s and to offer counter histories that reveal divergent, non-White experiences with Modernism. Conversations on race are especially important in today’s political climate and Wilson, a White scholar, strives to open one up with this book. Her conclusions, while compelling, would be more robust and persuasive had she centered the voice of more African American designers, activists, and academics. Nonetheless, it is a fascinating and important read for a popular audience.

***

For more information on Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design, visit the Princeton University Press website.

**

Erika Balcombe is a design anthropologist, educator, and museum collaborator who studies people and their relationships with things. Ever wondered how the built environment expresses cultural values? Erika does, and that’s why she works with design students, cultural institutions, corporate workplaces, and local communities to better understand human experience in architecture space and the meanings ascribed to them. You can find some of her creative projects on her Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/erikas_good/.