This is the first of a four-part series of articles exploring the Environmental Assessment process and how it’s shaping Toronto. The series will focus on four major developments currently at the EA stage.

![]()

Of the people, for the people, by the people.

Sure, Lincoln may have been referring to American governance in his Gettysburg Address, but his words stand for Ontario’s Environment Assessment Act too. Indeed, the Province inscribed our primary environmental planning tool with Lincoln’s sentiment: “The purpose of this Act is the betterment of the people of the whole or any part of Ontario by providing for the protection, conservation, and wise management in Ontario of the environment.”

But how well does our Environmental Assessment Act work? Does this safeguard ensure that our environment is protected? Does it facilitate the betterment of the people of Ontario? How would we know if it did?

Over the course of this four-part series, I’ll be assessing the Environment Assessment (EA) process. Using the lens of four major projects currently winding their way through the bowels of the EA system, I hope to share some perspective on the nature of the process and its success in protecting our environment. First up: the Gardiner Expressway and Lake Shore Boulevard Reconfiguration Project.

Initiated in 2008 by the City of Toronto and Waterfront Toronto, a corporation set up by federal, provincial, and municipal authorities to oversee revitalization of the waterfront, the Gardiner Reconfiguration will determine the future of two major arteries and reinvent our relationship with the waterfront. Because of the scale and nature of the project, it been termed an “Individual Environment Assessment.” With an eye to the potential for large environmental impacts, the Ministry of the Environment requires that a Terms of Reference (ToR) document be produced to guide the EA process. Think of the ToR as a map to guide us from an infrastructure idea to a (hopefully) revitalized reality.

The City and Waterfront Toronto released their ToR in September of this year. It’s an impressive document, packed with holistic — if lofty — goals like revitalizing the waterfront, reconnecting the city with the lake, balancing modes of travel, achieving sustainability, and creating value. (For an overview, see Jake Schabas’s post on the subject from this past summer.)

The retained consulting firms, Perkins+Will, Morrison Hershfield, and Dillon Consulting, have put together an extensive plan to integrate considerations of urban design and environmental impact in the EA process. They justify the need for this project to “address current problems and opportunities…includ[ing] a deteriorated Gardiner Expressway that needs major repairs and a disconnected waterfront…revitalizing the waterfront through city building, creating new urban form and character and new public realm space” and define the criteria for judging potential solutions to these problems (variables of urban design, transportation, environment, and economics).

Because the Gardiner alone moves more than 200,000 vehicles each day, and because many Torontonians are concerned about the future of the waterfront, stakes for this revitalization project are high, opinions are fervent, and the visions are contentious.

Nowhere is this tension more clear than in the e-consultation record that Waterfront Toronto has developed (www.gardinerconsultation.ca).

One participant writes: “All the words I have heard and read about the ‘revitalization’ of the eastern waterfront have been said before, almost verbatim, years ago…I find nothing in the planning for this area that acknowledges the mistakes of the past and defines the assurance process that it is not going to happen again.”

Indeed, even with good intentions, the strongest safeguards, and the best-laid plans, we don’t really know what beasts we may unleash in the Gardiner Reconfiguration process. The EA lacks any mechanisms to assess where we’ve gone wrong in the past or to evaluate how successful our current projects are five, ten, or 50 years down the road.

The ToR empowers the participants in the consulting process to determine the criteria by which we will weigh our options. But what if we pick the wrong objectives? What if we don’t represent the opinions of everybody who needs to be accounted for?

Another participant exhorts: “I encourage people to try and think beyond your commute to work tomorrow and to think about the future and what we want to leave the next generation.”

Future generations play no part in the EA process. Though they will live with the consequences of our decisions, their needs are not explicitly addressed in consultation or assessment.

The ToR is now in the hands of the Environmental Assessment Branch at the Ministry of the Environment. Pending their approval, the EA will soon begin in earnest. The year-long process will require public consultation, assessment of the undertaking, consideration of alternative options, descriptions of environmental impact for each course of action and an evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of each. The proponents estimate that the EA process will cost $7,697,929.

By January 2011, a complete EA document will be submitted, circulated, and evaluated by federal, provincial, and municipal authorities before a summary joint review will be released. Following 30 days of public comment, the MOE will accept, reject, or request modifications to the document. If accepted, a 15-day public review will follow. During this time, members of the public can request a hearing. If the Minister opts to hold a hearing, testimony may be given by proponents, reviewers, and the public to inform the EA Board’s decision. The Minister then has 28 days to accept or rescind the Board’s decision.

It’s a long and winding road from proposal to EA-approved project. An expensive round of consultations, analyses, evaluations, and revisions is the strategy we’ve chosen to check and balance our biggest development decisions. In the coming articles, I’ll look at the Scarborough Rapid Transit and Don River and Central Waterfront EAs to further deconstruct this process. Finally, I’ll provide an assessment of whether the EA process is really serving to better the people and environments of Ontario.

Next time: The Scarborough Rapid Transit Extension.

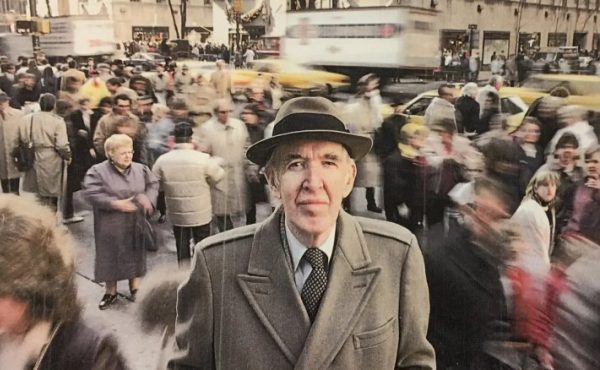

photo by Isaac Peters

9 comments

Interesting article, but perhaps you could elaborate on what exactly the EA process is, how and why proponents are subject to it, and what the implications of the EA process are. There is often misunderstanding amongst the general public as to just what an “EA” is, if indeed they have even heard of it before.

When writing about the SRT project, be sure to include the information that the entire process was heavily biased toward an extension of the existing RT technology, but that, in the end, the TTC and Metrolinx have finally seemed to agree that it should become an LRT line as part of the Scarborough network.

All of the consultation to date has been based on a technology and implementation that is not what is likely to happen. Why? It’s the story behind the EA, of the decisions and political pressures that appear only in finished form in staff and consultant recommendations with the exception of being rubber stamped by a public that isn’t given the alternatives to chose from.

I look forward to this series. I hope you can take a step back and discuss the future of the EA process itself. It seems to have evolved in Canada into an omnibus planning consultation, with elements of design review, economic benefit-cost analysis, and cooptation of NIMBYs. All excellent things, but needing a clear framework, and why in heaven’s name is it guided by the _Environment_ Ministry?

Why is the Gardiner EA going to be evaluated by the federal government?

I agree with other posts – you definitely need an Environmental Assessment (EA) primer included as part of this series. For example, not only the details about the structure and rationale for an EA, but the relationship and roles of the Ontario and Federal EA process. Although an EA can be annoying and slow, when examined closely, the process steps actually make sense – and most people would not disagree with this content. However, problems often occur in the application of these policies and processes.

The article really needs focus. Discussing the EA legislative framework would be the proper starting point. I’d speculate the legislation is beyond its scope when it is used to evaluate a proposed project on a piece of land that has been industrialized for a 150 years.

Like the waterfront, this is complex.

For perspective on some of this, and EAs, check in to Steve Munro’s blog; it’s helpful. Not as helpful as having direct, heads-on experience with both the EA processes and the at-times abysmally short-sighted and inadequate EA processes with waterfront transport planning processes.

This has been honed by tilting at windshields with the Front St. Extension process – where the majority of councillors originally supported a massive road project to alleviate/redirect a chunk of the Gardiner – but they and the EA processes completely failed to think of Transit provision first as an option.

There are about 10 or 12 transit options – some of which are still viable – and that’s where EAs should begin – though the province was far smarter than the City and expanded the GO trains by two cars and thus eliminated any real need for the FSE.

Analyzing demand, and origin-destination is a key part of any EA – and it’s also really helpful to have a look at the original WWLRT EA – it pointed out that a Front St. transitway is actually more useful and effective ie. doing direct.

Because the real problem of the waterfront is less of the Gardiner and far more of the cars on it.

To have relevance too, please think of the absolute travesty that our progressives and conservatives have gone ahead with on Bloor St. in Yorkville. The City has basically broken the EA Act by fudging what category the streetscaping is in – the division between a Class A and a Class B project is $2.2M; and the decision to categorize should be done “inclusively” which I take to mean not doing any cherry-picking.

But the cost of the Yorkville project is $25M – and

even consultants would have a really difficult time to justify $25M fitting under a $2.2M tipping point.

While there’s absolutely no assurance that an EA on a street/road project does improve bike safety, for some of us, that’s been a major shortcoming, and it’s made more galling as there’s plenty of waste space between new curb and new planter that if made into bike/road space, could! provide us with the option for bike lanes in a corridor (Bloor) so logical it was in fact the first choice for an E/W route in 1992!

Of course getting into the details of an EAvasion in our own territory isn’t nearly as exciting as what other areas are doing, and suggesting that we’re not so “green” as sooo many Councillors, the Mayor and bureaucrats and city ads is uphill.

More details on Bloor at takethetooker.ca and for overall cycling usage, please look at this.

http://www3.thestar.com/static/googlemaps/100105_bikes.html

EAs and biking are another topic; consider looking at the ECO for further info/perspective too.

When you finally get around to evaluating whether the EA process has been helpful or problematic, do not forget to consult the Environmental Commissioner’s Office (ECO) annual report of 2007/8 (I think). They pointed out numerous problems in the process, including the fact that virtually none of them are ever rejected.

Although it is mentioned that a description of EA will be presented in the following articles, to add a little bit of a context a quick overview might include…

Environmental assessment is essentially a form of logistical step-by-step deliberation and decision-making that investigates the likely environmental (understanding the broad term to include the physical, social, and economic environment) effects of a proposal. It also tries to ensure that the knowledge gained is effectively incorporated into the selection, design, and implementation of the proposal. The point of EA is to attempt to identify potential effects, identify and propose measures of how they might be avoided and mitigated, and to then evaluate (or compare) the benefits and costs of the project and predict whether there will be significant adverse effects even after mitigation measures are implemented.

Environmental Assessments are conducted at both the federal and provincial levels and are a product of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act. In order for a project to be subject to the federal level it must be triggered by at least one of four factors: it is on federal land, funded by federal authorities, the feds are the RA (responsible authority), or it appears on the Law List (for example, a project that would affect a lake would require a federal approval because it is subject to the Fisheries Act).

Environmental law in Canada is tricky because there is no harmonization between the federal and provincial levels; jurisdiction is determined by the Charter resulting in different laws and processes between all ten provinces (where territories are federal jurisdiction). Therefore the Ontario Environmental Assessment Act and the way EA is conducted is different from Alberta, BC, etc.

In Ontario, projects are automatically subject to EA if they are a proposed by the provincial or municipal government and can be applied to private projects if dealing with waste management or electricity generation. Ontario follows a Class EA process (with a total of 11 classes) and most projects are only subject to a screening (99% of projects) but in bigger and more complex projects such as the Gardiner Revitalization, they are subject to an individual assessment (a comprehensive study that often requires the inclusion of a review panel). Since the project sets off a “trigger” (there is both federal money and it is subject to the Law List) it also requires the federal EA process.

The general format of an EA is:

1. Determine if an EA is required and identify who is involved (who is the RA, who are the key stakeholders)

2. Plan the EA (where in the provincial EA, the terms of reference will be laid out)

3. Conduct the Analysis and Prepare the EA report

4. Review the EA report

5. Make the EA decision

6. Implement and follow up on the decision

What is absent from this very brief outline is the inclusion of public participation. The literature suggests that the public be involved from the beginning, to be included and consulted from the earliest stages included the development of the terms of reference and valued environmental components (VECs). However, the literature also suggests that this is both costly and time consuming and not required by the proponent. While the public does have to be consulted, it is unclear at what stage in the process this needs to occur. Furthermore, it is argued that the strength of the EA is in decline and needs to either be entirely revamped, or abolished and redrawn. What we (as the public) can look towards is other avenues for exercising our environmental rights (ie, Ontario’s Bill of Rights Registry) in an attempt to effectively contribute to the decision-making process.