Some time ago, I created some lessons plans about the urban environment for grade 7 students. Those 12-year-olds had mastered the water cycle years before – evaporation, condensation, precipitation, infiltration – but had no clue how potable water gets delivered to our taps, and where it goes once it’s flushed down the drain. The worst part was that, despite having a degree in Environmental Science from a Montreal university, I was barely any more knowledgeable.

The reason for our ignorance soon became evident, as I invested hours into collecting information and images for what would amount to a 50-minute lesson: Honestly, what teacher has time for this? While primary and secondary schools focus on province-wide curriculum objectives and standards, universities purport to prepare graduates to enter a global job market. Neither level of education aims to accompany students in decoding the specificities of the local environments that we navigate every day.

Fortunately, it turns out that 12-year-olds tend to pay attention when their classes include maps and photos of their own neighbourhood (or even better, the unseen infrastructure beneath their feet). If there are any teachers out there who would like a copy of the slideshow, please in touch by leaving a comment (only the author will see your email address). This topic is a good fit for the MELS secondary cycle 1 geography course.

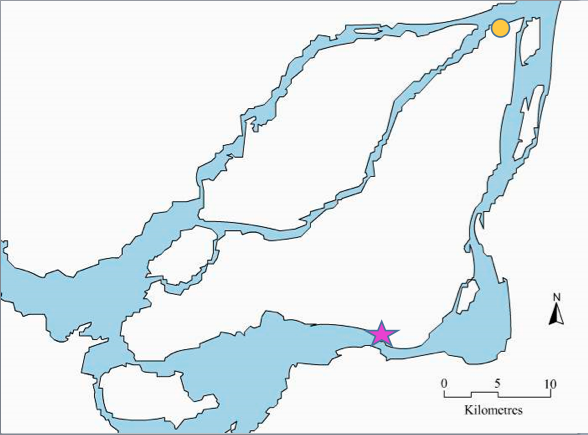

Montreal is an island in the St-Lawrence river. Pretty much all the water that we use in Montreal – for drinking, cooking, bathing, washing our clothes, watering the grass, and flushing the toilet – comes from the river, and returns to the river. The same is true for water used in our schools, restaurants, factories, etc.

In the map above, the orange dot and purple star show the water intake and the waste-water treatment plant. Do you know which is which? If you aren’t sure, consider which way the Saint-Lawrence river flows (hint: it starts in the Great Lakes and ends at the Atlantic Ocean). What side of the city would you rather drink from?

PART 1 – Getting clean water to our tap

Near LaSalle (the purple star on the map) some of the river water is diverted into an-open air canal that brings the water from the St-Lawrence to the water treatment plan near Atwater street. The canal was built in 1856, and is about 8km long.

Later, a second water filtration plant was built in LaSalle. At the water filtration plants, the water is filtered and ozonized to kill all the germs and bacteria. Then some chlorine is added to make sure that the water remains sterile as it is distributed throughout the city.

Montreal’s two water filtration plants clean 2.4 million cubic metres of water every day. That’s enough to fill about 960 olympic-sized pools! Yet only about 1% of that water is used for cooking or drinking.

Next, water travels through pipes called aqueducts, to underground pools called reservoirs.

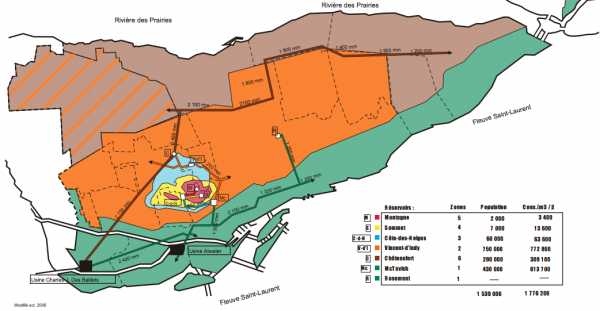

Reservoirs exist so that we don’t run out of water right away if anything anything ever breaks at the filtration plant. There are 6 different reservoirs in Montreal, all on or near Mount Royal. The reason that water is pumped all the way up to Mount Royal is because that makes it easier to distribute it to buildings all through the city: gravity does most of the work.

In the map below, you can see which reservoir stores water for your neighbourhood:

Our school, which is located in St-Henri, is fed by the McTavish Reservoir. McGill University’s football team practices on the field on top of the reservoir.

Finally, the clean water flows through aqueducts under the streets to all the buildings in the city. The city has over 4000km of aqueducts that distribute water to every building in the city.

Unfortunately, many of these aqueducts are very old and leaky. In fact, about 30% of the water that we clean at the water filtration plant leaks out of the pipes before it even has the chance to get to our homes. This image shows city workers replacing water pipes in NDG.

So that’s how water gets to our taps, hoses, toilets, washing machines, and water heaters. Yet almost as soon as we turn on the tap, water rushes down the drain or flushes down the toilet, and begins its journey back to the St-Lawrence River…

PART 2: Waste-water treatment

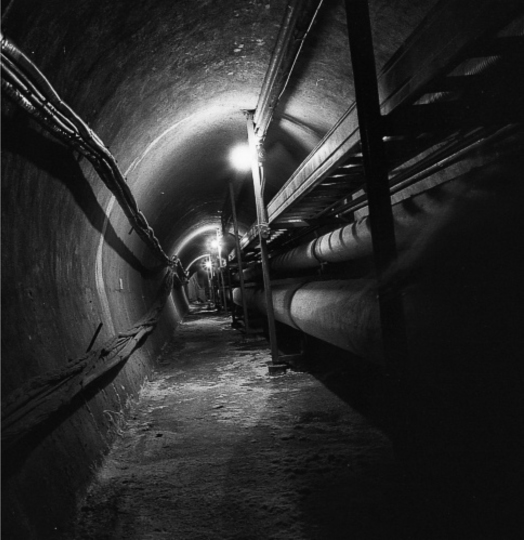

Water that goes down the drain, it ends up in the sewer system. Some of the sewers in downtown Montreal are very old, like this one, in Pointe-St-Charles, which was built out of bricks over 100 years ago.

But 100 years ago, theses sewers used to dump directly into the Saint-Lawrence river at the nearest point.

Did you know that Montrealers used to be able to go swimming at beaches on the banks of the St-Lawrence river? By the 1940s, people began getting sick from swimming in such dirty water, and swimming was banned.

Montrealers knew that polluting our river was causing major problems, but it wasn’t until 1987 that Montreal’s sewage treatment plant was built and running.

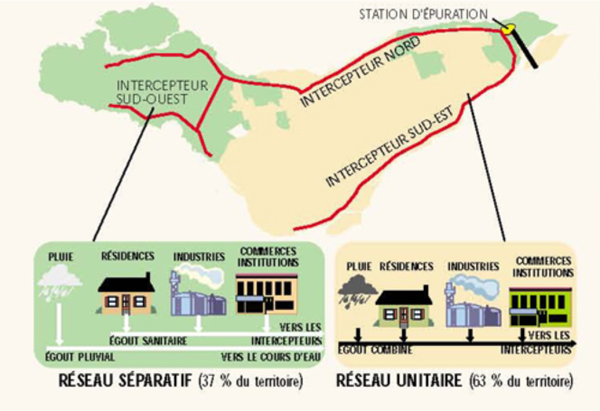

In our neighbourhood, as in most of the city, we have a “combined sewer system.” That means that the dirty water from our toilets, drains and factories, goes into the same sewer as the rain water.

These days, rather than dumping directly into the river, the sewers all flow into a sewage collector, which runs all along the edge of the island. Once again, gravity does all the work. By the time it gets to Pointe-Aux-Trembles, at the east-most tip of Montreal, the collector is as wide as a metro tunnel, and is 46 metres underground.

At the sewage treatment plant, the dirty water is pumped back up to ground level. Then it is filtered to remove things like sticks and toilet paper. Next some chemicals called coagulants are added to the water. These stick to smaller particles and make them sink them to the bottom of the pool. All the solids are then removed from the water and burned. The ashes are sent to a landfill.

Right now, Montreal’s sewage treatment plant doesn’t include any disinfects to kill germs and bacteria before dumping the water back into the river. Because the sewage plant treats so much rain as well as sanitary waste, it would be very expensive to disinfect such a large amount of water. However, the city hopes to add a chemical disinfecting process called ozonation soon.

Meanwhile, after 25 years of sewage treatment, the Saint-Lawrence river is clean enough to go for a dip along the shores of Montreal.

Sources: Much of the information presented here synthesized from articles published on Spacing Montreal and other blogs. “Advanced learners” can delve deeper into the history and detailed workings of Montreal’s water infrastructure:

- History of the Aqueduct Canal by Andrew Emond on his blog Under Montreal.

- Historical link between water and democracy by Alanah Heffez

- Virtual visit to the water treatment plant by Jacob Larsen

- History of the debacles of building the waste-water treatment plant by Andrew Emond.

- Virtual visit to the Montreal’s waste water treatment plant by Alanah Heffez

10 comments

Super interesting, and thanks for the extra resources!

This is really amazing, thank you! I have been trying to figure this out since I moved here over 4 years ago, and you’re right, when you have so much else to do as a teacher, it’s easy to give up. I would love a copy of your resource! Most of all, thank you for putting in the time and energy to put this together. This is such important information, and it’s presented very clearly and in an interesting format!

I would be very interested in receiving this resource. You have done an amazing job to develop this lesson plan(s).

Ray

Howdy!

Very nicely done, congrats. Two small things; a) I strongly doubt that the Redmen still practice on top of the reservoir. And b) is it possible to get a larger copy, or a link to the original of http://spacing.ca/montreal/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2013/12/Screen-Shot-2013-12-08-at-9.08.06-PM-600×311.png? Please and thank you. It is very difficult to read at that resolution

I love it! I substituted in a grade five social science class in Cotes-de-Neiges recently. They had been studying the historic St. Lawrence valley and the river and were very keen. I asked them to name an island in the St. Lawrence, and it took them some time to come up with Montreal or Laval! Most of them had no idea they were living on an island, let alone where that island was located, despite having studied the St. Lawrence! I would love to have a copy of your slide show!

Eve in Cote-des-Neiges

@Zeke, Here’s the link to the pdf: http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/EAU_FR/MEDIA/DOCUMENTS/stations_pompage_reservoirs_territoire_usines.pdf

I also updated it in the post above

Hi! Super interesting article (and I can only imagine all the work that went into it!). I work for an éco-quartier and we often do environmental presentations in classes. Would it be possible me to have a copy of your original slideshow? Thanks!

Love this article! I am doing my thesis on the McTavish reservoir and would love to take a look at your presentation. Hopefully when I am done, if you are interested, I could forward you the research I have done!

thanks so much

Wonderful article — thank you! I am teaching a CEGEP course on “Cities” and will certainly reference your work for our unit on infrastructure. It would be great to see your slides as well!

Hello,

great article, help me so much. I’m a master student in civil engineering and a study on energy generation from wastewater. I need help with finding some data about the Jean-R Marcotte wastewater treatment plant. I’m an international student and have no clue where I should look for this information. I really appreciate it if you can help me with this.

thanks.