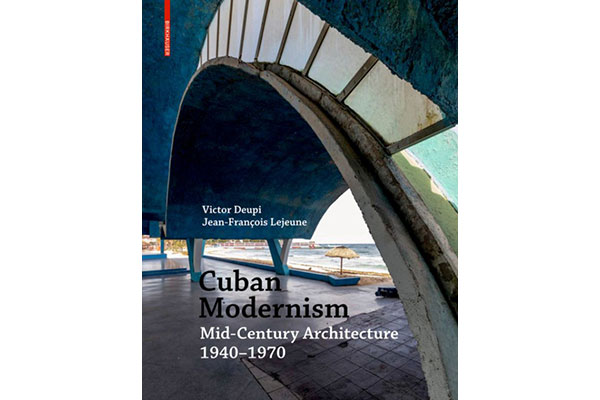

Authors: Victor Deupi & Jean-Francois Lejeune (Birkhäuser, 2021)

In the 20th century, modern architecture thrived in Cuba and a wealth of buildings was realized prior to the 1959 revolution and in its wake. The designs comprise luxurious nightclubs and stylish hotels, sports facilities, elegant private homes, and apartment complexes. Drawing on the vernacular, their architects defined a way to be modern and Cuban at the same time – creating an architecture oscillating between tradition and avant-garde.

—From the Introduction

In this new 344 page book spanning three decades of Cuban architecture, authors Victor Deupi and Jean-Francois Lejeune have done a commendable job of filling in some of the gaps on the subject, along with providing English translations of many Spanish architecture texts here available for the first time. For as they note in the book’s opening pages, the majority of knowledge in North America and Europe on the subject has typically been derived from two architecture surveys: Sigfried Giedion’s A Decade of New Architecture (1971) and Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s Latin American Architecture since 1945 (1955).

Given these two texts, along with two shows on the origins of Latin American architecture put on by MoMA in 1956 and 2015, this heroic volume is a much-needed addition to the topic. Based on an exhibition held at Coral Gables Museum in South Florida in 2016, the book includes a new collection of current photography by Silvia Ros, accompanied by a rich archive of historical images, city plans, and drawings. Just as astonishing is the academic rigour with which the authors have researched and presented their subject, including an alphabetical list of 40 Cuban architects at the end of the book.

With a comprehensive introduction entitled ‘Modernity and Cubanidad,’ the book’s ensuing chapters explore the nation’s architecture starting at the scale of the modern house and progressing to that of the city. Later chapters are devoted to architecture and its relation to recreation (‘Tropicality, Tourism, and Leisure’) and the arts (‘The Synthesis of the Arts’). Placing the chapters in this order, the book becomes more autobiographical than chronological, showing, in general, the relationships between domestic and public architecture in the city, while simultaneously providing contemporary planning frameworks at both the rural and urban scale.

The second chapter is perhaps one of the book’s most fascinating, as it looks specifically at the planning and growth of Havana, including the building of its civic precinct and surrounding landscape like the Malecón, with a spotlight on Josep Lluís Sert’s Plan Plato de La Habana (1959). The chapter reinforces the author’s main thesis that the city became a petri dish of mid-century modernism, with ideas from the likes of Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier being tried and tested as the city continued to grow.

The book also shows the connection of mid-century modernism to the Havana School of Architecture, whose students burned copies of Vignola’s classical orders on the steps of the school in 1944 to protest the rigid canon being taught. Perhaps the most pivotal moment for Cuba was when Walter Gropius visited and spoke at the school in 1949, with the authors of the book likewise pointing out that modern architecture had been written about as early as the 1930s in Spain, primarily in the country’s two main architecture magazines, El Arquitecto and Arquitectura.

Another highlight for the Havana architecture school was its patronage by Josef Albers who lectured there between 1934 and 1952, with the book’s authors noting that the school curricula at the time would have been greatly influenced by the writing and built work of such European architects as Gropius, Le Corbusier, and J.J. Oud, all of whom were well documented in El Arquitecto and Arquitectura at the time. The authors also cite the influence of Richard Neutra, who visited Cuba in 1945, giving a lecture at the Havana architecture school entitled ‘Architecture and the World of Today.’

But without a doubt, it was the arrival of Josep Lluís Sert in 1939—when he and his wife spent a few months in Havana before his starting to teach at Harvard—that would have had the greatest influence on Cuban modernism. During his few months in Havana, among many other things, he set up a local branch with the CIAM called ATEC, translated to Tectonic Group of Contemporary Expression.

The first order of business for the Havana-based group was “to study and resolve the architectonic and urbanistic problems in Cuba, always in the present and towards the future.” And it could truly be said that one of the most compelling images in the book is Sert’s 1959 plan of Havana on page 116. More than just an urban design drawing, it constitutes the city’s break from its near 400-year colonial history, representing a new contemporary world view for the country, for its architects, urban planners, and artists.

The authors in Cuban Modernism effectively illustrate how the combination of these influences at the Havana school of architecture at that time created a whole new generation of modern architects in Cuba, noting that at the same time there were some critics who felt functionalism shouldn’t overrule vernacular considerations and that modernism could be perceived as just another form of colonialism. A more regional response would consider both the local climate, cultural, and political factors that a functional plan could not anticipate.

As well, Deupi and Lejeune encourage the reader to look beyond Cuba for its influences—not just to schools of modernism but to other more traditional, vernacular influences in other parts of the world, explaining that “historians need to reach beyond the confines of Cuba, situating Cuban architecture in a broader context by examining its interaction with other centers of modern culture such as the wider Caribbean, Latin America, North America, and Europe. Lesser-known architects, women, and minorities need to be seen and heard.”

And whether or not you’ve ever visited the Plaza Vieja in Old Havana or the resort strip of Varadero, Cuban Architecture is an armchair traveler’s delight, providing hundreds of images from both the city and the countryside. As well for the academic, it is a rich source of both architecture and urban design, and a must-read for both the architecture historian and practitioner, architects and city planners alike. Cuban Modernism is a visual tour de force and a new, indisputable encyclopedic resource of modern Cuban architecture.

***

For more information on Cuban Modernism and its authors, go to the Birkhäuser website.

**

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect and the current RAIC regional director for BC and Yukon.