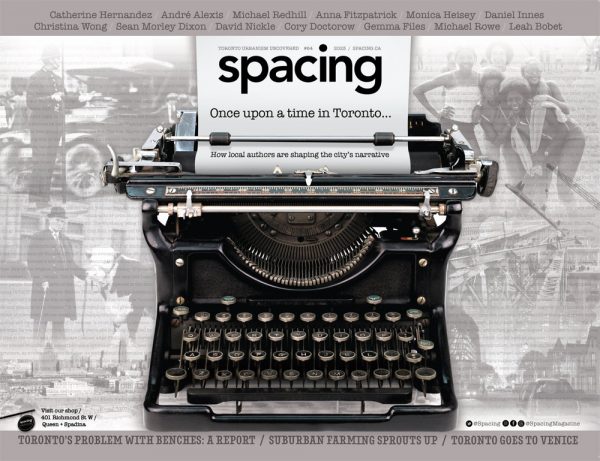

Novelists mine the past, mirror the present, and imagine the future to create the settings for their stories. When their novel is set clearly in a particular city, that city itself can become one of the characters. It shapes the story, and at the same time its own story starts to be shaped by the writer. The accumulation of these stories becomes an overall narrative of the city’s past, present, and future, a kind of lens that enhances and overlays the reader’s vision of the urban landscape. In this issue, we decided to explore how writers, especially novelists, have engaged with Toronto – how it affected them, and how they in turn affected the city’s imaginary.

In the past few years, I’ve made a conscious effort to read more novels, trying to alternate between non-fiction and fiction books. I’d previously gone through a long phase of mostly reading non-fiction, and started to realize that I missed experiencing other people’s imaginations. I had devoured genre novels as a teenager – science fiction and fantasy – and then in my twenties started to read more literary fiction. A lot of that focused on Canadian writers – Davies, Atwood, Oondatje – and many of those books were set in Toronto. It was a city I was just getting to know in reality, and at the same time I was getting to know literary versions of it, adding an extra layer of imagination to the everyday city and its people.

I drifted away from novels as I got more involved in current issues and spent leisure time on non-fiction – still stories, but grounded the real world and real people. But then I married someone who loves novels and is a writer herself, triggering my renewed interest in fiction. My recent novel reading has been more eclectic than in the past, with stories from all over the world. But some of them have been about Toronto, such as André Alexis’ Fifteen Dogs and Zalika Reid-Benta’s short story collection Frying Plantain (both mentioned in our cover section).

The Toronto we find in contemporary fiction is a much broader, richer stew than it was in my earlier readings. It covers far more geography – the entire amalgamated city – and a much broader range of people. It also, as we explore in our cover section, covers more genres. There’s much more speculative fiction set in Toronto these days, delving into alternative presents and possible futures. There’s also more of other genres. One of my former day-job bosses published a romance novel set in City Hall (in which a cameo character on one page bears a faint resemblance to myself), and Amy Lavender Harris’s map of Toronto literary scenes in this issue features another romance novel scene also set there. It might seem like an unlikely romantic setting, but of course we’ve recently discovered it can indeed be a real-life locus of illicit liaisons.

The most recent Toronto-set novel I read is Anna Fitzpatrick’s Good Girl. Fitzpatrick works for Spacing in our store at 401 Richmond Street W., so I think of her as our in-house novelist. We of course got her to write for this issue. A common piece of literary advice is “write what you know,” but she explores the degree to which that can be awkward in writing about one’s own city. And after all, what makes writing fictional is writing what you don’t know, adding something more to the familiar – as she notes, creating something the people who know you won’t necessarily recognize, and that will expand the way they think about the city rather than simply reflect it.

The stories in our front section also expand the way we think about the city – even all the way to Venice, where Christopher DeWolf reveals that Toronto has a role in the Venice Biennale of Architecture. Ian Darragh’s writing and photography, meanwhile, take us to many corners of the city to meet the people developing urban agriculture for Black and other communities. Jillian Linton takes us on a challenging transit tour of the GTA, and AccessArt gives us a new way to look at public art through the lens of accessibility.

In a special section on benches, Cara Chellew and John Lorinc analyze why these modest elements of public infrastructure are vital for public spaces, and how Toronto neglects them. Drew-Anne Glennie, meanwhile, provides insight into how such public spaces build empathy – a role fiction has also been shown to play. In a sense, fiction is our literary public space.

Both fiction and non-fiction tell us stories about our city, revealing new ways of seeing it and of experiencing it. Each has a role in shaping our image of Toronto. As for my novel-reading, editing this issue has provided me with a future reading list I am looking forward to working through. We hope that our readers find similar inspiration.