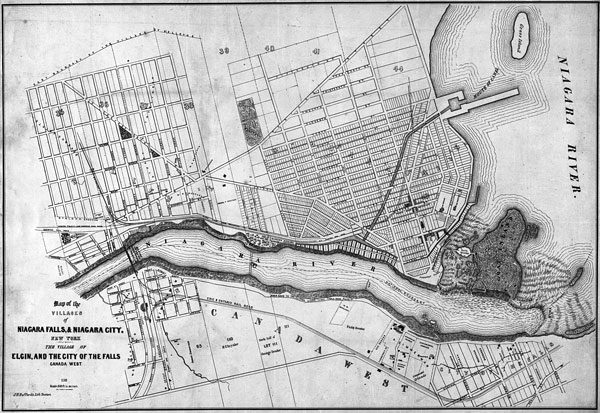

Humanity’s collective drive towards urbanization within the past century has gone hand-in-hand with the mindless erasure and destruction of past urban environments. Historic preservation of historically significant architecture and districts has helped to cull this tide, yet the prevalent modes of preservation tend to focus on buildings, often at the exclusion of the underlying historic settlement patterns that inform a city’s historical development.

These patterns – much like the architecture that encloses the places we inhabit – have a logic and intelligence, founded in the socio-cultural values and geography of a particular place. They contribute to the organizational systems that underlie our settlements by dictating public space and street dimensions as well as lot and block sizes. They also reveal how our ancestor’s social and cultural values were embedded within their collective context and used to live more harmoniously with one another and their surrounding environments than most cultures today.

With the unparalleled power of contemporary civilization to rapidly alter the landscape and build at ever-increasing scales, the erasure of the underlying pattern of countless settlements has never been so prevalent. Their destruction is, in fact, encouraged within the culture of how we currently build. Large block and multi-block development and lot amalgamations, for example, characterize today’s construction practices as financial concerns are translated into building regulations.

When these patterns are destroyed, we lose much more than sites of antiquarian interest. We lose sight of a way of city building that is increasingly relevant to the goals and ambitions of contemporary urbanism. More specifically, these sites demonstrate an environmental intelligence and connection to the surrounding landscape and climate that we are currently striving to re-establish, are valuable examples of human-scaled settlement that promote human well-being and comfort, and foster the creation of resilient, adaptable communities through the small dimension of their city structure.

Environmental Intelligence

One of the most significant values of historic settlements is that all facets of their creation have an intimate relationship with their surrounding natural contexts. The form and layout of the street, lot and block systems all responded to topography, solar exposure, soils, and other climatic phenomena.

We can look to the well-known ancient Greek “solar city” of Priene (400 BCE), for example, to learn how a gridded block pattern, integrated with the surrounding topography and positioned according to solar orientation, set the foundation for an architecture that brilliantly reconciles human use with solar exposure.

The historic fabrics of Eastern settlements show similar characteristics. The hidden urban structure that supports the architecture of Old City Beijing, for example, was carefully calibrated to balance socio-cultural needs with the realities of its natural context. In real terms, the architectural order of courtyard buildings and the urban pattern they created, crystallized social structure, cultural values, urban structure, built form, climate and geography into a cohesive whole. Several other non-orthogonal cities such as Tunis in Tunisia and Mardin, Turkey also demonstrate an intelligent integration with the surrounding natural environment.

As a shelter for environmental intelligence rooted in sustainable practices and a connection to surrounding environmental systems, the urban framework of our older settlements offers a valuable repository of concealed wisdom worth learning from, emulating, and building upon based on our newly acquired knowledge of the many different environments around the world. Our growing awareness of the nuances of climate and geological processes – among others – can and must be integrated with the keen observations and built practices of the past.

Human scale

There is a growing awareness in city planning best practices that the scale and grain of a city’s inhabited spaces is critical to human comfort and well-being, and that this, in turn, is closely related to the underlying structure of its form. Although the specific measures of length and land subdivision in historic cities were often idiosyncratic, derived from anthropomorphic units of lengths (the Egyptian cubit for example), or from context specific behaviors such as walking or farming (the 15 ft. right-of-way of the standard Roman streets of 15 BC, for example, was born from the dimensions of horse carts), the resulting patterns related extremely well to the human body.

The important adaptation of city pattern to human senses and dimensions of the body – championed by strong research of people like Jan Gehl – is often first sacrificed by contemporary forms of development. Between tight time lines, the increased speed of transportation methods and the massive scale of developments, new urban areas are often far removed from human scale and comfort.

Similarly, given that the lot and block dimensions inherent to past urban pattern are closely tied to higher densities – a quality closely tied to supporting transit and commercial activities – their value as models for today’s urbanism is clear. Vancouver, Canada, for example, is constantly touted as one of the most livable cities in the world and has developed an innovative urbanism that is intimately related to its original standard 33’x120’ lot structure. This is also evident in the ‘Compact City’ initiative evident in Europe that promote walking and cycling, low energy consumption and reduced pollution living.

Resilience and Adaptability

The implications of the human-scaled lot sizes common to traditional city structure reach further than human comfort, for history shows that they perform better over the long term, as well. At a time when complex global forces are increasingly volatile and unpredictable, the creation of resilient and adaptable communities fostered by the small lots is becoming more and more important. Smaller scale patterns make communities more robust through tempering large-scale transformations to communities under pressure.

Anne Vernez Moudon’s seminal work on the physical transformation of San Francisco—Built for Change—is an important testament to how a community’s ability to evolve and change relates to the hidden traditional framework that supports it. By ensuring that property remains in many hands, she writes, small lots bring important results: from ensuring variety in the built environment through the different decisions of many to slowing down the rate of change by making large-scale real estate transactions difficult.

Large lot patterns with fewer owners, on the other hand, are susceptible to the potentially unpredictable change in reaction to unforeseeable outside forces. This is explicitly evident in the transformation of vibrant traditional commercial areas that have been selectively transformed by large, multi-lot footprint retail stores. As the volatile nature of recent global influences force large-footprint retail space out-of-business, it often creates sizeable “activity voids” along an otherwise energetic street. In many cases, these oversized spaces lie vacant for long periods of time due to their size. The large scale of these spaces, in turn, prevents the opportunity for small, incubator, start-up businesses to contribute to and maintain the vitality of the area. In this way, the large lot developments typical of contemporary development practices can also have potentially disastrous long-term economic impacts.

Although few studies have been done on the properties and performance characteristics of different settlement patterns over time, those that have been conducted – such as Arnis Siksna’s influential studies on the study on block size and form – clearly reveal the advantages of small/medium blocks and lots common to traditional settlements in virtually every category.

Interestingly, Siksna’s research goes further to expose how different large block and lot sizes tend towards similar subdivision patterns over time – demonstrating explicitly how the large development patterns in Adelaide, Australia and Toronto, Canada, for example, have been subdivided or broken down over time, effectively approximating sizes and dimensions similar to the older patterns of cities such as Savannah, Georgia and Portland, Oregon.

On Preservation:

The study of traditional city patterning suggests that there are universal principles of scale, dimension and environmental responsiveness underlying good settlement design. The violation of these principals, and the consequent failures in city building we see today, points to how significant the hidden pattern is for our collective future.

We must try to preserve and learn from what is left of the historic and hidden patterning of our cities while being mindful of the dangers of our heritage and preservation tendencies that result in petrified building fabrics, which are closed to change, and therefore must rely on other unpredictable factors, such as tourism, to keep them vibrant.

The preservation of the hidden settlement patterns of the past is not opposed to change. To the contrary, the fact that many of the patterns still exist today speaks to their merit and durability. Change is a necessary for built environments to survive. By virtue of their strong logic and (universal) principles, the abstract lines of historic settlement patterns accommodate transformation of all types – such as changes in technology and building practices – while remaining firmly rooted in the common human values that created them.

As the foundation of what makes the built environment succeed and/or fail, the significance of preserving our hidden settlement pattern lies beyond the architecture that it supports and perhaps even the past cultural values it embodies, to a way of thinking that we must re-learn – standing on the shoulders of all those who came before us – if we are to confront the future boldly and confidently.

***

This piece was originally published in Sitelines Magazine (June 2013).

**

Erick Villagomez is one of the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.