The day after the kettling at Queen and Spadina, arguably the nadir of the G20, street artist Posterchild went to work. Reminders of the night before still lingered in the humid, late June air, the trauma something like a hangover. Only hours earlier, the Integrated Security Unit — a paramilitary, improvised federal police force held in the government’s back pocket for state events like these —had ensnared hundreds of Torontonians, some not even there to protest.

It was the largest mass arrest in Canadian history, and to much of a Toronto public that had no say in hosting it — or the desire to, for that matter — it was ominous, like Stephen Harper himself had annexed Hogtown for the week. It felt darkly like martial law.

You can readily imagine Posterchild sharing those thoughts. Early the following morning, the stencil artist arrived at the stretch of Dupont Street beneath the West Toronto Railpath, near the threshold of the Junction Triangle. On the north side of Dupont, the concrete meets a set of stairs that ascend to the boardwalk overhead. Here, on a re-purposed stretch of railway infrastructure, is one of the most publicly-oriented pieces of Toronto’s urban geography, used by cyclists and pedestrians and an inclusive cross-section of the city. A sense of grassroots solidarity somewhat defines the place as a result, a civic worldview enshrined beautifully on the south side. Splashed across that side of the street, a mural of cogs and bike parts stretches from end to end, lighting up Dupont with an eye-popping, arresting burst of colours. Painted cyclists ride motionlessly in either direction, meeting at the center beneath the words, “Strength in Numbers.”

As if a counterweight to everything defining that spirit, Posterchild’s addition was a glaring fixture against such a backdrop. Clad in the Darth Vader-black gear of the previous night’s riot squad, the prime minister’s face grinned at pedestrians approaching from the east, a shield emblazoned with the name “Harper” in his left hand. In his right, a truncheon hung at the ready.

With the hard stenciled outlines, he appeared boastful, even a little menacing.

In a word, Posterchild was pissed. “I’m just so upset at everything, like a lot of Torontonians,” he later told Torontoist in an email. “But I have had trouble sorting out how to express it. I was not sure where and how to express it.” With the prevailing confusion and deep, shattering anxiety that followed all the raids and beatings of that weekend, Posterchild’s email perhaps spoke for more than he realized at the time. We were all voiceless. From the beginning, when the G20 was announced as Toronto’s problem in 2009, the public was effectively locked down, denied its own agency by the state.

Worse, it’s like public engagement itself during the G20 was made illegal altogether. In the ensuing silence, Posterchild’s simple, angry, tongue-in-cheek portrait of Stephen Harper thundered.

Disasters often come to mind when the question of urban resilience is raised. Climate change, terrorism, major natural catastrophes — it’s the response to these sorts of calamities, when such a response yields minimal public impact, that sets the standard for a city’s capacity to bounce back. “At first flush,” wrote Bruce Watson in The Guardian’s January 27th, 2014 edition, “resilience seems a clear lens for addressing the problems of cities.” It’s a more inclusive, rounded idea of a city’s hardiness, he writes, than the usual questions of sustainability or livability. “Resiliece,” he adds, “reflects a city’s ability to persevere in the face of emergency, to continue its core mission despite daunting challenges.”

Which suggests that there are defining questions about urban resilience beyond the availability and funding of emergency services, or even the health of infrastructure. There’s the pestering itch of those words, “core mission.” In a municipality like Toronto, the Jane Jacobs-esque idea of a city — public, inclusive, a living thing as much as a livable one — has the role of an engaged, constructive public at its heart.

And when suppressed — by an overzealous police force, an incompetent mayor, take your pick — the loss of that essential public role threatens civic disaster.

The Toronto G20, of course, isn’t the only recent example of this peaceful resistance in action. Before the lighting of the Olympic cauldron, opposition to the Vancouver Olympics of 2010 went back years, especially locally. And to many Vancouverites, there was good reason. “There are so many people in poverty in this city,” wrote Rabble’s Am Johal in February, 2010. With a massive population affected by crises ranging from homelessness to mental health to addiction, such an historic expense — $1.76 billion, by 2009’s estimates — seemed out of place at best in a city with so many needs.

“As thousands prepare themselves to attend Olympic events,” Johal continued, “there are thousands of others who have been totally neglected by the advance of the Olympics.” Support, he wrote, had stalled at around 50%.

Like Toronto, Vancouver had its own provisional police state, presided over by its own Integrated Security Unit. But in contrast with the Toronto G20, the chronology of resistance to the Olympic Games was almost the G20’s inverse, while still amounting to the same loss of public agency. Across Vancouver, art had long been the narrative of protest, going back to the city’s first pronouncement as host seven years earlier. Notably, one example included a Beatty Street underpass, once the location of a mural commissioned by the city in 2007. Perhaps in anticipation of the Olympics, it was painted over in late 2009, replaced by a wall more blue than Vancouver’s sky half the time.

It was almost the perfect canvas. Across its surface, a stencil appeared of the Olympic rings, framed by the words, “With glowing hearts, we kill the arts.”

Ultimately, it’s the role of intervention — as visible and in-your-face as possible — that makes the arts such a powerful, far-reaching voice, and the public’s most effective agency when other such means are restricted. Think back to 2012, during that year’s student protests in Quebec, when ATSA—Action Terroriste Socialement Acceptable, or “Socially Acceptable Terrorist Action” —dramatically opposed the veritable state of martial law enacted by the Charest government in response. Though none were injured, the detonation of three smoke bombs in the Montreal Metro snarled traffic for three hours, and the response was as if the state had actual, violent terrorists in its crosshairs.

When it was legally demonstrated that police were essentially penalizing performance art — through a trumped-up charge of “inciting fear of terrorism” — charges were dropped, and the discussion shifted to a state playing fast-and-loose with legal definitions in order to suppress dissent itself.

In Toronto, it could be argued that this need for a public voice continues, and that the role of art in restoring it has never been more important than during the age of Rob Ford. Throughout Toronto, from North York to Kensington Market, Ford’s face has appeared in every stylized street format imaginable. On stage, even, Toronto’s least inclusive, most divisive mayor is soon to be the subject of a musical. One of Ford’s first acts in office was to eliminate the citizens’ advisory committees, among the public’s most effective conduits of engagement at City Hall before their removal. It’s as if he planned to close Toronto’s society from the outset.

The arts, however, have played a critical role in ensuring he hasn’t.

It’s an unfortunate truth that public, grassroots art as a form of protest is normally a temporary thing, fleeting in a way that authorities might find convenient. Posterchild’s Harper was lost to Ford’s anti-graffiti free-for-all early in his term as mayor. The art of Vancouver 2010, of course, was painted over almost as soon as the Games began. ATSA’s work, on the other hand, continues in a gallery format, allowing the public to engage with that art up front.

But as long as dissent exists — arguably a given in an era of mounting austerity — what makes art the intangible lifeblood of urban resilience remains. And it’s normally in giving a voice to voiceless sentiments like this:

“I don’t like you, Mr. Harper,” Posterchild wrote on his blog, not long after gracing Dupont Street with his work. “I don’t like what you’ve done to my democracy, my country, and my city.”

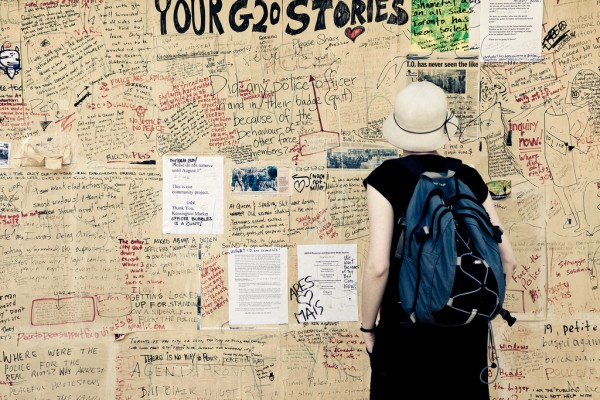

Top photo by Sam Javanrouh