Workers replacing Old City Hall’s roof pose by a gargoyle overlooking Terauly St (now Bay), 1920.

Workers replacing Old City Hall’s roof pose by a gargoyle overlooking Terauly St (now Bay), 1920.

In the 1890’s, long trains loaded down with beige sandstone chugged from New Brunswick to Toronto. E.J. Lennox’s magnificent Old City Hall, once the second largest city hall in North America (after Philadelphia), enriched with flamboyant romanesque details, finally opened for civic business in September 1899 after ten years of construction.

What reverence Torontonians had for the building was not shared by the harsh Canadian climate. The freeze-thaw cycle had an appetite for delicate sandstone gargoyles and finials, culminating in 1938 with a 500-pound chunk of gargoyle from the clock tower crashing through the roof of the building. A year later the weathered beasts were all removed along with other ornaments as a safety precaution. Old City Hall was becoming soot-blackened and weather-worn.

Grassroots community uproar spared the building (just barely) from a 1960’s plan which would have left only the clock tower standing like an obelisk in a sea of austere concrete. Since that reprieve, epic restorations have been carried out. A team of 30 metal workers recently spent five years replacing the copper roof, and decades of grit has been scrubbed off to reveal pristine red and beige sandstone. New gargoyles have been cast in durable lightweight bronze, restoring the tower’s original proportions and gazing out over a city much changed in their absence.

Old city hall clock tower in 1923, clad in wooden scaffolding.

Old city hall clock tower in 1923, clad in wooden scaffolding.

The steep roof, at 75 degrees of pitch, made work a challenge. 1920.

The steep roof, at 75 degrees of pitch, made work a challenge. 1920.

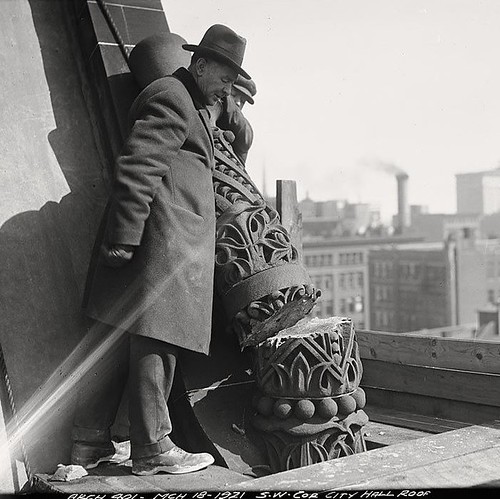

Removing a stone finial in 1921.

Removing a stone finial in 1921.

Slum houses, rear of 21 Elizabeth Street, 1913. Looking east to city hall. Hard to imagine now that New City hall and Nathan Phillips Square are built on what was once a poor part of town called The Ward, which for many years sprawled beneath the snouts of city hall gargoyles.

Slum houses, rear of 21 Elizabeth Street, 1913. Looking east to city hall. Hard to imagine now that New City hall and Nathan Phillips Square are built on what was once a poor part of town called The Ward, which for many years sprawled beneath the snouts of city hall gargoyles.

All photos are from the City of Toronto Archives.

15 comments

Much of the New Brunswick sandstone sent to Ontario came from my hometown of Sackville. I had heard that this included Old City Hall, but (with only a quick search) can only find confirmation for a touch-up of the provincial legislative buildings.

The more interesting story is where the sandstone comes from today. Mount Allison University, in Sackville, was built almost entirely with sandstone from the Sackville quarry just metres from campus – an extremely local materials supply! The new buildings that they have created in the last few years have also been built of sandstone. But this sandstone is quarried in England, processed in China, and then shipped back to New Brunswick for construction in Sackville. That’s a little less energy-efficient.

http://www.billhamiltonflashback.ca/listnews.php?id=108&cid=1&searchtext=&offset=10

http://heritage.tantramar.com/WFNewsletter_5.html

That’s some kind of neo-sandstone-mercantilism.

It’s great that city hall is being restored but it is absolutly insane that tonnes of heavy stone are shipped around the world between three continents to save a bit of labour cost. No wonder our economy is where it is now. And could anyone think up a way to burn a bigger carbon footprint if they tried?

Amazing photos.

Boris: I do not think Laura was saying that the sandstone used to do the renovations to Old City Hall a couple of years ago followed this amazing England-China-Canada course – which does seem very odd! I think she was talking about Mount Allison University.

I think the sandstone and roofing parts of the Old City Hall renovation are now finished. I think the next phase is windows and, one hopes the removal of the ugly window air conditioners.

Yes, it would be a great thing to see those air conditioners gone (and replaced with a less unsightly means of air conditioning).

David, you’re right that I was referring to Mount A. But I’d be curious to find out where Toronto’s sandstone comes from today.

I was under the impression that much of the stone to build Toronto’s downtown buildings (including city hall) came from the quarry off Bayview now called the Brickworks.

Many bricks came from (were made in) the don valley brickworks, but not stone. There are Ontario stone quarries though, not sure about sandstone.

I’ve read that the reddish stone of old city hall was sourced more locally – credit valley sandstone from NW of the city (near my hometown of Orangeville). Likewise the pinkish stone of Queen’s Park parliament buildings. Lots of small quarries still operate in the area, many along the niagara escarpment.

What happened to the original gargoyles?

I think they were destroyed in the removal process. They each weighed a couple of tons, and would have been very difficult and expensive to remove without chipping them into pieces.

The sandstone for the legislature is coming from england, depending on the complexity of the cut it is cut in england, in toronto, or on site.

I’m on the site.

To rdaner and Matthew (several months after the fact),

Yes, the original gargoyles were destroyed in removal. Because of that and because there were no pictures (apart from silhouettes) of the actual tower gargoyles, the creators of the new gargoyles didn’t try to replicate the originals. I humbly point you to my book which includes the stories of the old and new gargoyles – Faces on Places: A Grotesque Tour of Toronto (Anansi, 2006).

The first gargoyle to lose a big chunk was the one on the NE corner of the tower. In March 1921 its 100 pound jaw section fell through the roof of City Hall. It narrowly missed a Works Department staffer working at a drafting table. After that, masons were ordered to prune the rest (Toronto Star 9 Mar 1921 p. 1). The modifications were still in progress in November 1921 (Toronto Star 1 Nov 1921 p. 6).

I think it was more than the weather which caused the gargoyles to crumble. The downtown atmosphere was heavily laced with the fumes of bituminous coal smoke, whose sulphur content would attack the metallic oxides bonding the sandstone together.

Terry & Richard, thanks for further illuminating the story.