Milne House (2008), photographed by Olena Sullivan

ED: Heritage Toronto’s Gary Miedema will be making a series of posts on structures around the city included in their upcoming “Building Storeys” exhibit at the Gladstone Hotel that runs February 17-22.

What do you do with an abandoned historic farmhouse that’s listed on the City’s Inventory of Heritage Properties, and now nearly strangled by bush in a Don Valley conservation area?

Next time you are stuck in northbound traffic on the Don Valley Parkway between Eglinton and Lawrence, you’ll be in a great place to ponder that question. After the railway underpass just past Eglinton, you’ll descend down into the bottom of the valley, which quickly widens out. Not far away, on top of the valley wall on the left, are 1950s Don Mills homes with backyard swimming pools. Invisible on the crest of the valley to the right are the sprawling industrial buildings of Railside Road. Down in the valley, where the highway is only a few feet above and beside the river, you are cruising through the ghosts of Milneford Mills.

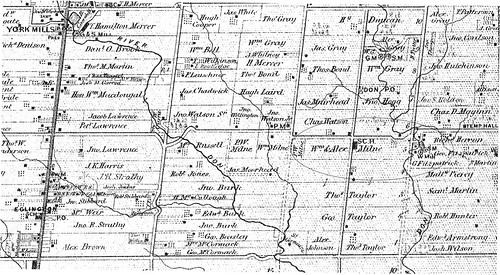

Detail from the 1878 Illustrated Historical Atlas of York County showing Milneford Mills (circled) in its larger context. Yonge Street, punctuated by the communities of Eglinton and York Mills, runs up the left side of the map.

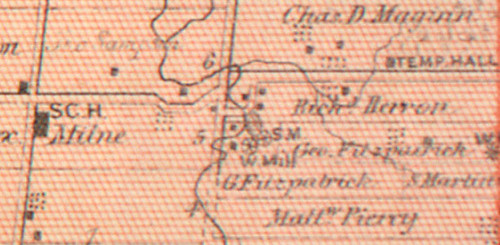

Detail from the 1878 Illustrated Historical Atlas of York County with today’s Lawrence Avenue detouring to cross the Don River at Milneford (centre of map). Black dots represent buildings. “S.M” represents the Milnes’ saw mill, “W. Mill” their woolen mill.

Details from the 1878 Illustrated Historical Atlas of York County showing a (no doubt embellished) Milneford, the 1878 Woolen Mill, and a Milne residence

In its heyday in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, Milneford Mills was a cluster of some 16 buildings. (An embellished lithograph made in 1878, shown above, portrays an idyllic valley scene). What is now Lawrence Avenue detoured down along the east valley wall, curved through the settlement, crossed the river, and made its way up the other bank to rejoin the straight concession line. Evidence from the census returns and period maps indicate that in addition to two water-powered mills, one a rare woollen mill, Milneford Mills boasted a dry goods store, a wagon shop, and workers’ housing. The homes and barns of the Milne family, proprietors of the whole business, joined them. Their fields stretched out of the valley, but an aerial photograph from 1939 still shows fields in the valley itself. According to an 1851 census, the Milnes grew wheat, peas, oats, potatoes, turnip, hay and apples. In around the homes and barns were “bulls or oxen, milch cows, horses, sheep and pigsâ€. Wool, fulled cloth, butter and pork completed the farm produce.

Only one Milneford building still stands today — barely. You can just see it from the DVP — a flash of white siding in the bush at the bottom of the valley wall off to the right. If you get off on Lawrence and head east, you can drive down old Lawrence Road into the Charles Sauriol Conservation Area in the valley. The house is in the trees nearly straight ahead before you take the turn at the bottom.

Though detailed records no longer exist, Milneford was likely already 30 years old when the house was built – between 1860 and 1865. The first Milne, Alexander, had already passed on the family business to his son, William, who would later pass it on to his son again. Late nineteenth and early twentieth century photographs show the home to be a classic Ontario Gothic Revival farmhouse — one full storey with the second under a pitched roof, and the faà§ade marked by a central door flanked by two identical windows with a gable above. This house deviates from the norm, in that its front and back faà§ades were a mirror image of each other — complete with off-centred gables and full-length porches. One side faced the road as it came down the valley side. The other side faced south to look down the valley to the woollen mill, no doubt the pride of the family. Photographs show farm buildings nearby, the valley wall behind the house (now forested) almost completely cleared of trees, and an elegant picket fence and gate posts separating the road from the house.

Milne House, showing much of its original detail circa 1955. by Ted Chirnside, Toronto Public Library

Given the history of the area, its something of a miracle that the home still stands. When one of Toronto’s worst floods tore through the valley in 1878, this house – perched close to the edge of the valley wall – survived. The lovely red and buff brick mill closed in 1911 and was demolished in 1946. Nearly all of the other remaining buildings were demolished in 1953 by Don Mills Development as they cleared the site for other uses. This home survived, and after being empty for more than a few years, was renovated back into a functioning home. Then, a decade later, the view out of the front windows of this remaining home took in the bulldozing of the valley for the Don Valley Parkway. With rushing traffic drowning out the sound of the river, the home’s view now took in the new ski hill behind the house on the east valley wall.

But for the rusting poles of the ski lift, the ski hill has since disappeared, and the Charles Sauriol Conservation Area has emerged. A process of naturalization is now underway. The gardens surrounding the home, long since abandoned, have been slowly reclaimed by the forest, nearly right up to the house’s walls. Milneford is all but gone.

Even the sole surviving house is but a sad shell of its former self. The home was occupied and in private hands until 1992, when it and a sizable bit of surrounding land was acquired to complete the Conservation Area. Sitting empty since then, water, fire and human beings have taken their toll. Never ornate on the outside, the little old home has nonetheless been stripped bare of its porches, summer kitchen, and finials on the gables. It is covered with modern siding, but a clear gap shows where the porch was once attached to the house. Doors and windows are boarded up, but people have on occasion torn holes through the wide nineteenth century planks of its walls and damaged the interior.

Milne House, 1983. City of Toronto

Milne House, 1997. City of Toronto.

That said, this old farmhouse has a survival streak a mile wide. A 2003 study argued that it was still a good candidate for restoration or renovation. Much of the tall sculpted mid-ninteenth century trim, for example, is still there, as are some original doors. Though owned by the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, the house is the responsibility of the City of Toronto, and City staff have been trying to keep the building from deteriorating further. A four year old roof keeps the water out, and fresh boards and screws cover old holes torn in the walls.

What this important little house begs for is a plan for reuse attached to money. It has no connection to City sewers and, in effect, it’s in a public park. But it’s bigger than most condos (600 sq. ft. per floor), and the view over river valley meadows should be fabulous. Above all, it is the last surviving touchstone to a long and important era in this valley’s history.

Written with Mary Ann Cross

Milne House is included in Building Storeys: A Photo Exhibit of Toronto’s Aging Spaces, held at the Gladstone Hotel from February 17-22. For more information, www.heritagetoronto.org.

14 comments

It makes me sad that Toronto allows it’s history to disappear like this. We should be investing in the needed repairs.

Thanks for the write-up. I first saw this through the bare trees not more than a month ago and thought WTF?

I would gladly live in it.

Matters very little about the electricity or plumbing.

I’ve dealt with such things in the past, with little discomfort, and would heartily embrace doing so again, since it might provide me with a sense of purpose and well being again

The house has electricity, and would operate just fine with a composting toilet or something of the like. Assuming somebody could find the money to fix the holes in the walls, your bigger challenge would be coping with the visitors to the park who would assume the house is a public building, and who would no doubt have a look in the windows to see what was up. Perhaps rebuilding the fence would help.

So when Metro built the DVP in the 50’s, they paved paradise and put up a parking lot.

Don’t spend a cent on maintaining this, it’s nothing special.

Perhaps it’s nothing special, but you have to make your case. I think a good case for preservation was made above.

Opinions take work to make them considerable.

The DVP was actually built in the 60s. The bottom part south of Bloor was finished in 1964 where it connects to the Gardiner. The Gardiner was built in the 50s. The DVP was to connect downtown to the “Toronto By-pass” highway, otherwise known as the 401. Great article, too bad the city lets so many historic gems deteriorate away until they’re too far gone to salvage.

Unfortunately, I think that this is beyond repair and that it would be uneconomical to salvage especially given that there is no plumbing. Unless someone wants to buy it and fix it up, tear it down.

No doubt this building has suffered under public ownership. That said, I’m glad to say that the Milne House is likely not too far gone. It’s had a few very rough years, but as of 2003, a study gave its structure the green light. It also still had enough of its original interior elements to make a restoration worthwhile.

Given City plans to make much more of the surrounding conservation area, it would make a fine trail centre, perhaps, with the upper floor for offices.

Or perhaps someone would want to live there, as they did until 1983. Imagine a long-term lease like the City has done on the Island?

There is full internal and modern plumbing, but the house is not connected to the City’s sewage system. Like many country homes, it used a septic bed, but my understanding is that is no longer legal down in the valley. Given new green composting technologies, sewage should not be a big issue, but the cost of general repairs certainly is.

Don’t preserve/restore it with my money.

If a building is worth preserving, public funding is unnecessary because its owners will make the investment or sell to those willing to incur the relevant expenses. Otherwise, it’s not “worth it”. (Whether a given historic preservation is worthwhile is debatable, and is best resolved by allowing its owner freedom to make all such decisions; thus, the property ought to be restored to the private sector). If preservationists can’t outbid those who have other plans for the building, then clearly their desire is inadequate. I say this as a lover of historical buildings.

Don’t spend my money on it.

If a thing is worth preserving, public funding is unnecessary because its owners will make the investment or sell to those willing to incur the costs of preservation. Otherwise, preservation isn’t worth it. (Whether preserving a given building is worthwhile is subjective and debatable, and is therefore best resolved by the freedom of the owner to make all such decisions; thus, the property ought to be transferred to the private sector.) If preservationists can’t outbid those who have other plans for a given structure, their desire is inadequate. I say this as a lover of all things historical.

wow why is that house still there me and my friends have broken into that place hundreds of times the place is haunted to