Scanning the fascinating images in Mark Osbaldeston’s second compilation about Toronto’s “alternate history,” — Unbuilt Toronto 2 — I found myself strangely unmoved by some of the architectural projects that never made the great leap off the drawing board. Unbuilt 2, in some ways, is a collection of opportunities probably best missed.

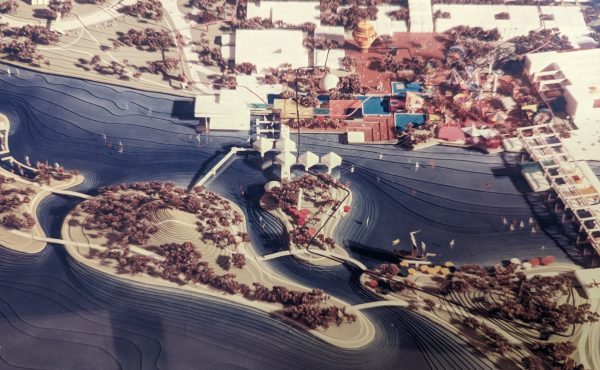

There are the monumental and vaguely totalitarian government and commercial structures from the earlier decades of the 20th century, as well as strange post-mo confections, such as Moshe Safdie’s jumbled plan for the old Maclean Hunter site at the corner of Yonge and Highway 401. From the space age 1960s, we have stadia floating in the lake, and a flared bottom to I.M. Pei’s CIBC tower that reminded me of nothing so much as bell-bottom pants. The heavy grid that undergirds the 1980s plan for the Ataratiri lands is crowded and deadening.

The cover image, of a possible Bloor Street wing for the Royal Ontario Museum (shown above), has the lovely feel of antique lithograph, inspired, as Osbaldeston explains, by a British architect whose resume included the façade of Buckingham Palace. Look more closely, though, and the façade turns its back onto Bloor while two Italianate towers loom inexplicably above the roofline.

Other examples, however, do inspire an acute sense of loss. The original 1973 plan for Raymond Moriyama’s Reference Library reveals a compelling five-storey glass box with a beveled corner and enticing visual connections between the street and the interior (think Four Seasons Centre). But public opposition to tall buildings forced Moriyama to add angled set-backs and implacable orange brick walls. Almost 40 years later, few could argue which was the better and more urban design.

Osbaldeston’s purpose, of course, is not to stand in judgment so much as it is to offer glimpses of how Toronto might have evolved had we/they made different choices. But it is difficult to read the chapters on some of the MIA transit plans without considering the political subtext of his archival sleuthing.

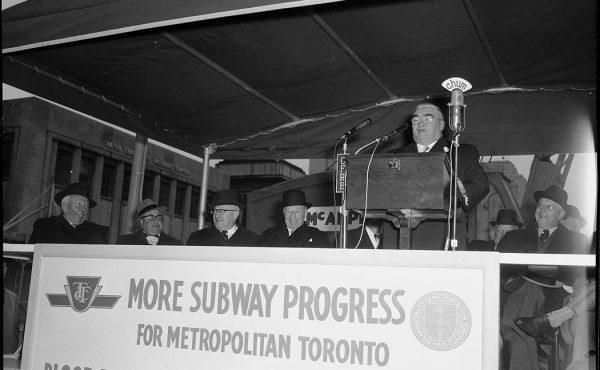

Exhibit A: the 1910 subway plan, which envisioned a circuit of three connected lines running west on Front, up Spadina to College, over to Dovercourt, then Bloor, Dundas, looping back along St. Clair to Broadview and finally down into the core. Another line would run up Yonge from Wellington.

Osbaldeston spares few details as he relates how this idea died on the vine of taxpayer parsimoniousness. With widespread public contempt for the city’s private streetcar operator, Horatio Hocken campaigned for mayor on a pledge to build “tubes” of the sort that were being dug in cities like Boston and New York.

“Although the voters rejected Hocken,” Osbaldeston writes, “they didn’t reject his vision, overwhelmingly approving a ballot question allowing the city to seek provincial approval for a subway system.” Queen’s Park promptly obliged with enabling legislation. The City, in turn, hired a New York consulting firm, Jacobs and Davies, to develop a plan. “The system would be fed by an expanded streetcar and radial system,” Osbaldeston says. “The entire tube portion could be build for just under $24 million.”

While the idea was to build the system in stages to contain costs, Toronto’s famously stingy voters did an about face in 1912 and voted down a $5.4 million bond issue needed to finance the first line to be built under Yonge.

Needless to say, Toronto would have become a completely different place –almost unrecognizable to the contemporary Torontonian eye — had those voters opted to support a transit plan they’d approved in principle only three years before. We can speculate, but it is reasonable to predict that such a transit network would have brought a denser urban form spread over a broader core area, more incremental additions to the subway network built throughout the century, and, perhaps, less second-guessing about the merits of rapid transit.

Indeed, one could argue that the most enduring legacy of that ill-considered No vote was the virus of political doubt that continues to infect our debates about transit fully a century later. `Unbuilt’ not just once, but over and over again…

Osbaldeston will be reading from the book tonight at the ROM. Details here.

2 comments

Amazing to think that 5 storeys was once considered “tall”.

I had a similar reaction to many of the abandoned projects in the first book – thank goodness these deadening monuments weren’t built.

If you miss Mark Osbaldeston at the ROM, you can catch him at the Toronto Reference Library on Monday evening, January 30, 2012 in the Beeton Auditorium at 7pm. as part of our Thought Exchange series.

http://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDM98473&R=98473