Cross-posted from No Mean City, Alex’s personal blog on architecture

![]()

What did we learn about building cities in 2012? From Superstorm Sandy, the lesson was that cities are not immune from the forces of nature. Wind and water trump steel and stone.

It was also, as the most powerful storm to hit New York in its 400-year history, a hell of a marketing event for climate change. This is not only a moral problem for the long term but also a practical challenge: where and how should we build our cities?

The wiser heads in landscape architecture are ahead of the rest of us – and their foresight produced real payoffs in New York. New redevelopment projects on the small Governor’s Island survived the storm, because landscape architects Adriaan Geuze and West 8 raised parts of the landscape 16 feet. (“I’m glad I hired a Dutchman,” says the island’s chief.) And on hard-hit Staten Island, some neighbourhoods were protected by the earthworks of Fresh Kills Park – a garbage dump that is being remade into a park by James Corner Field Operations.

Those two projects reflect the growing ambition of landscape architecture, Both those firms are working in Toronto right now, too.

And one of the biggest Toronto design stories of the decade will be the opening, in 2013, of Don River Park – which is built on and around a landform that will protect downtown Toronto from flooding.

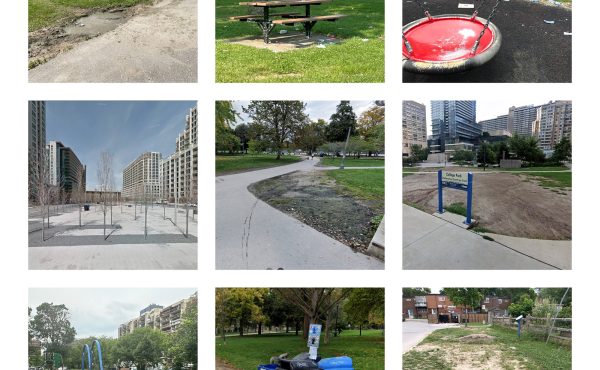

Designed by Michael van Valkenburgh Associates, another world-leading firm of landscape architects, the 18-acre park includes the Flood Protection Landform, a raised berm along the Don River that MvVA has transformed into a deep-rooted meadow. (More on that later.) The rest of the park includes marshes, lawns, a “mall,” a recreation field and a square – providing the terminus to two new boulevards that will define the area.

The surrounding context is incomplete. Buildings to the north and west are springing up in time for 2015, when they will become the Canary District, initially the athletes’ village for the Pan American Games. But much of the park is already built. (And the streets are mostly open. Go bike or drive through there! It is an incredible thing to see this much city getting built at once.) Even with the construction cranes, it’s clear that this large park will be an act of city-making on a remarkable scale.

And it is also a powerful example of how landscape should be responsive to environmental and climactic concerns. The Flood Protection Landform, 20 acres in size and only about four metres high, was built with 400,000 cubic metres of fill. It is big, and yet fragile; it will be landscaped with an “upland meadow” featuring native plants including goldenrod, Canadian wild rye and black-eyed Susans. No trees, though. Why? If a tree falls in a major storm, its root system would rip out of the ground and allow floodwater to breach the berm.

This is important, because the berm will protect a large area more than 500 acres in size – not just the immediate area, the West Don Lands, but also all of Toronto’s financial district.

Yes: Bay Street downtown sits in the flood plain of the Don River and it would be vulnerable in case of a major storm. Swamped streets, soggy subway tunnels, ruined boilers – all the chaos that was visible in Lower Manhattan could also happen here. The filling and building of the Don River’s watershed, which replaced marshland with fill to create the Port Lands to the south and this area to the west, destroyed the landscape’s natural capacity to cope with flooding.

Such a storm is estimated to be likely once in every 350 years. But as Sandy reminded us, unlikely events happen all the time, and those predictions about when they will come are worth less each year. In Toronto there’s precedent in living memory for such a storm: Hurricane Hazel in 1954, which wiped out development that had filled much of the Don and Humber River valleys.

In New York, there’s been some serious discussion about how Sandy might transform people’s perceptions about living near water. Some people have even mused that Lower Manhattan’s waterfront districts will permanently lose their value. It’s harsh to to say, but they should lose value. Large storms will happen again. Those boiler rooms, if they’re still underground, will flood again. Equipment will be destroyed. Buildings will go dark.

And it can happen here. Will we be ready? Thanks to the Don River Park and the deep, thoughtful work that’s going into it, downtown Toronto will be more ready than it has ever been.