Over the next several weeks, Spacing will be publishing a series of articles from Concrete Toronto: A Guidebook to Concrete Architecture from the Fifties to the Seventies (Coach House Books, 2007) as a companion of Spacing’s summer 2013 issue focused on Modernism.

![]()

Toronto’s New City Hall is fortunate to retain a small collection of its original office furniture, providing an interesting glimpse into contemporary Canadian furniture design and Toronto’s exploration of modernism in the 1960s.

After citizens voted down a proposed City Hall building in classical style in the 1950s, Finnish architect Viljo Revell’s design was selected following the 1958 international City Hall competition. The cultural implications of this selection were significant, resulting in Toronto’s first modern concrete civic building (the seat of government, no less) prominently located in downtown’s Victorian context.

Revell subsequently proposed to design office furniture for the new building and called City Council’s decision to award the furniture contract by a second international competition (held in 1965) the biggest disappointment of his life. As Revell passed away before the final results of the competition, judges felt an added responsibility to award the contract to Knoll International, stating, “More than any other competitor, this firm’s designers seemed to have caught the spirit of the building and maintained it consistently in major as well as minor areas … In addition, it was the opinion of the Committee that the Knoll International submission was one that would not have been displeasing to Viljo Revell himself.”

The late 1950s to ’60s were a time of design innovation in the Canadian office furniture sector, with the Robin Bush Prismasteel design and Jacques Guillon’s Alumna office desk — with patented slotted-leg extrusion — appearing in 1958 and 1961 respectively. During this time, European furniture masters like Klaus Nienkamper and Leif Jacobsen arrived and set up shop in Toronto, later to expand or be consolidated into larger companies (Jacobsen’s company was purchased by Teknion). The award of the City Hall commission to American-based Knoll, who collaborated with local Leif Jacobsen, had an effect on Toronto’s furniture-design scene similar to the effect the award of Massey College to Ron Thom’s office had on the history of the city’s architectural production.

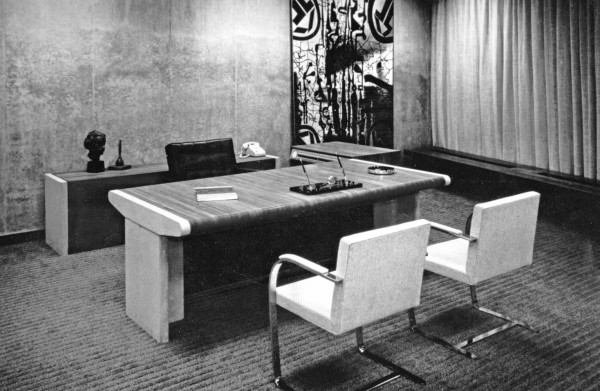

While the Knoll competition entry was not alone in pursuing a contemporary design, it was unique in its use of concrete and its direct response to the building. Like its host, the furniture, ranging from clerks’ to Council Chamber accommodations, capitalizes on the colour, texture and sculptural possibilities of its materials. Desks and benches feature massive, precast concrete bases, oiled white oak casings with Arborite top surfaces. Furniture for the east tower, which caught the afternoon sun through its west-facing windows, was upholstered in cool shades of blue and green. The west tower’s upholstery was in warm shades of yellow, gold and orange.

Scandal immediately erupted over the new furniture. For reasons that remain unexplained today, the selection committee voted on the entries without opening the envelopes containing cost information until after the winner had been announced. Knoll’s bid was found to be over budget, and other competitors complained it was unfair to award the contract to a company that had not followed the requirements of the competition. Several months of wrangling between the selection committee, the Board of Control and City Council followed over what one newspaper called questions of “ethics and aesthetics.”

When the dust settled, Knoll had reduced the cost of its bid and was allowed to fulfill the contract. Mayor Philip Givens, who supported the Knoll entry, stated, “Design is the guts of the situation. Otherwise we could have ordered from a catalogue.”

The furniture’s building and completion were considered newsworthy, and once installed, the furniture’s use continued to be controversial. Newspaper headlines included “Drawerless Desk Fine with Him,” “Furniture Row’s on Again” (referring to the coincidence of desk transparency with new, shorter hemlines – “vanity panels” were later installed), “Wobbly Desks at City Hall Spark New Furniture Controversy” (stenographers complained that desks moved as a result of typing despite their enormously heavy concrete bases), “Furniture Fine in Pictures But … ” and finally, “Bell Quits after Row over Desks.”

Given Toronto’s optimistic response to the design of New City Hall, it seems strange that such controversy could follow its office furniture. Perhaps the equally modern furniture design, with its mimetic use of concrete, served as an outlet for the undercurrent of anxiety about the insertion of a new form of expression into the city’s fabric (construction of New City Hall was completed in 1965, the same year as the furniture competition).

Since the 1960s, a large portion of the collection was lost through renovations, as the weight and character of the furniture was not popular in later decades. Recognizing its value, Marc Barness, a former Director of Urban Design in the City Planning Division, began to collect the original furniture in the late 1980s. Today, the City Planning and Urban Design offices at City Hall continue to be a repository for the remaining original furniture, housing its largest collection, which includes chairs, desks, tables, bookshelves, credenzas and coffee tables. It remains in daily use and continues to be at risk of replacement. Original furniture (circular lounge chairs and coffee tables) can also be found in the Council Chamber members’ lounge.

Still in use over 40 years later, City Hall’s tiny extant collection of original office furniture continues to be sturdy and beautiful, although in need of some restoration and not terribly convenient for movers. The 1960s controversy over its procurement, design and early use attests to the long-standing willingness of Torontonians to debate passionately the design of our city and to City Hall as a banner for design innovation. It is reminiscent of recent public debate over buildings whose architectural expression is unhabitual for Toronto, offering insight for the present and future. The loss of most of the original collection is a timely reminder that the fabric of our public realm, be it furniture or architecture, cannot be evaluated merely on the criteria of ‘new’ or ‘old,’ nor can we afford to privilege the iconic over the mundane.

– by Marsha Kelmans

2 comments

Recommended: The 99% Invisible podcast on this topic (highly, highly recommended podcast for the Spacing set)

http://podbean.99percentinvisible.org/2011/02/25/99-invisible-17-concrete-furniture/

This Concrete Furniture looks really cool. I just bought a concrete dining table for my home at Mecox. I loved the look and they are so durable. It gives the room a warm, yet modern touch.