Atlanta, GA, the sprawling southern metropolis, has followed a classic pattern of modern North American urban growth. As the city developed over time, its land uses grew less and less integrated, necessitating a pattern of auto-centric design and movement and outward growth. This physical problem, caused by the separation of uses in the name of public safety, has, in turn, sparked social problems — a lack of connectivity and walkability and a heavy reliance on auto use resulting in impacts on physical health, wellness, and social cohesion.

And as Atlanta grew, so did the problem. But proposed solutions remained rooted in long-standing cultural expectations of what a city should be: built for the car, with distinct residential and business districts, and ever-expanding.

But what if we framed our solutions with a new question: what kind of city do we want to be? If we want to live healthy lives, stay connected to one another, participate in a thriving economy, and enjoy public space and civic life, why don’t we rethink the city from there?

That was the starting point for Ryan Gravel’s masters thesis in city planning and architecture at Georgia Tech. Gravel looked to a 22-mile loop of former rail corridor circling downtown Atlanta as a source of huge potential for achieving the kind of city he wanted to live in. Gravel believed that the rail corridor could serve as the basis for a public transit and trail corridor that would encourage private capital to invest in the downtown and reinforce the redevelopment of a compact, walkable, transit-oriented, and vibrant central city.

Through advocacy, local organizing and support from civic leaders, Gravel’s thesis project transformed into the Atlanta BeltLine, a $3 billion public works project that is one of the most comprehensive urban redevelopment projects in North America today. The Atlanta BeltLine will integrate this abandoned 22-mile railroad corridor into a network of transit, pedestrian and cycling routes, as well as public parks, integrating affordable housing, public art and historic preservation and connecting 40 diverse neighbourhoods in downtown Atlanta. In this way, the BeltLine is very much a comprehensive urban development project — considering transit, housing, connectivity, and economic development as interconnected parts of a whole, to shape the kind of city that Atlanta wants to be.

It’s a massive project. Some trail segments and parks have already opened, to rave reviews from locals and visitors, and some residents have settled into new affordable housing units, but the entire project will take two decades to complete. Ultimately, 3,000 acres of previously underutilized land (mostly rail corridor and former industrial sites) will be made available for public and private redevelopment. Socially, the BeltLine will connect 40 distinct neighbourhoods across barriers of race, class, and wealth, in a city with a history of spatial segregation. The BeltLine is transforming the physical form of Atlanta, but also the way that people think about and live in the city.

The positive impact of parks investments is well demonstrated (and will be explored in Gravel’s forthcoming book). But what is of particular interest here is the impact of the Atlanta BeltLine as a comprehensive investment in parks, trails, transit, housing, and economic development. As downtown Toronto faces significant development pressures, communities are increasingly looking to edge spaces and infrastructure corridors as potential open space assets, to be transformed into linear parks and railpaths. Taking notes from the Atlanta BeltLine, we should consider these projects from a city systems perspective–what is the potential for transit, active recreation, enhanced urban design, and good development along these new linear parks, and how can we harness that potential to build the Toronto we want?

With the success of local rails to trails projects (think West Toronto Railpath and Kay Gardner Beltline Trail) and larger-scale precedents abroad (like the Atlanta BeltLine), Toronto parks and trails advocates are looking for new ways to incorporate existing assemblages of open space and infrastructure corridors into the public realm, re-thinking these spaces as key physical, social, and economic connectors, as well as new public parks.

One such project here in Toronto is the Green Line, a 5 km linear network of open space beneath a hydro corridor, stretching from the south corner of Earslcourt Park and hugging the north side of the Dupont Street rail corridor to Davenport Road. Currently, some sections of the Green Line route are well used, with children’s playgrounds, sports fields, allotment gardens and splash pads. However, these animated public spaces are interrupted by parking lots, fencing, and poorly maintained areas, as well as troublesome grade changes, leaving the Green Line disconnected as a whole. But the potential for the Green Line as a catalyst open space project is evident.

Organizing to transform the Green Line into a continuous public space gained momentum with the 2012 launch of an ideas competition by Workshop Architecture (in partnership with Spacing and others). The competition invited designers to develop a comprehensive vision for the Green Line as a whole and to develop unique solutions to enhance connectivity across an existing intersection and railway underpass.

In a central city facing immense development pressures, the potential of the Green Line as an existing assemblage of open space to enhance our park and trail network is huge. The space could not only serve as a public linear park and recreation amenity, but also facilitate east-west pedestrian and cycling connectivity though mid-town Toronto. The Green Line could also catalyze a new type of development in the area. It could generate a new urban form along the Dupont strip, connecting neighbourhoods that have been separated by the rail and hydro corridor through built form and public realm design that stitches together both sides and establishes on the open space as a focal point. It could be integrated into the City’s recent study of the Dupont Employment Lands and to the area’s overall development as a mixed use area of higher density. The Atlanta BeltLine considers open space, transit, movement, housing, and economic development comprehensively. This kind of systems thinking should be encouraged along the Green Line, too.

A Friends of the Green Line group has recently formed (with the help of Toronto Park People), and is working to advance their vision for the Green Line as a public open space through advocacy and organizing. When it comes to new public space in the city, the Friends of the Green Line understand the importance of identifying and accessing that “low-hanging fruit”. The space exists–it’s just a matter of stitching it together.

Not to make it sound simple. This kind of project would require a significant capital investment from the City and a commitment to ongoing maintenance costs, not to mention political will (which, in Toronto’s Ward system, could be difficult to achieve for projects that span the jurisdictions of multiple Councillors, like the Green Line). And plans for the Green Line should be integrated with ongoing plans for the future development of the Dupont Corridor as a higher density, mixed use area of residential and employment uses.

But organizing by local parks and trail advocates around key edge spaces like the Green Line, based on a shared vision of the connected, walkable, green city that we want Toronto to be, is a good start.

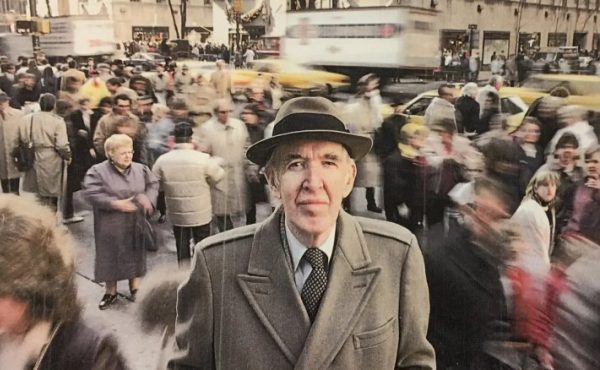

Ryan Gravel is now a Senior Urban Designer with Perkins+Will and design manager for the Atlanta BeltLine Corridor. He will speak at Urbanspace Gallery here in Toronto on July 8th at a free talk presented by the Centre for City Ecology and Toronto Park People on the Atlanta BeltLine and the potential of investment in non-partisan public works projects to enhancing livability, connectivity, and social cohesion in our cities. RSVP here.

Image by Flickr user cantabjrc.