In 1959, the builders of Regency Acres, a 700-home subdivision in Aurora, Ontario, offered something no other homebuilder in the country could: a private, family-sized nuclear fallout shelter.

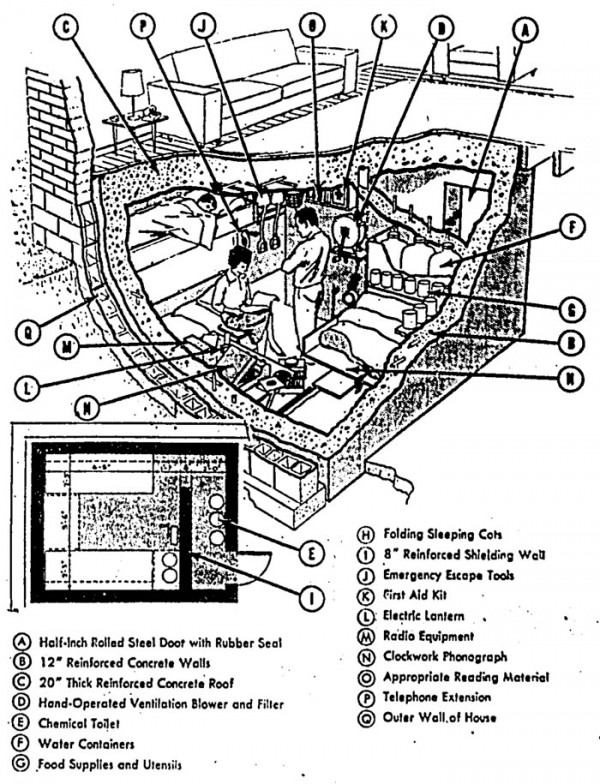

For an extra $1,500 on top of the sale price, Consolidated Building Corp. Ltd. would install a reinforced concrete bunker in the basement of any of the 20 styles of home available in the subdivision. The 3.3 x 2.4 metre rooms had 30-centimetre thick walls, a filtered air system, and a rolled steel door with a thick rubber gasket.

Safe from the toxic ash raining down from above, a family of five sequestered inside would sleep on folding cots and subsist on filtered water and canned food. For entertainment, a clockwork record player and “appropriate reading material” would also be provided.

The set-up “should allow a family to remain relatively comfortable for the seven to 14-day danger period,” the Globe and Mail reported.

The shelters at Regency Acres were the first to be offered as a standard feature of a new home in the Greater Toronto Area.

One of the prevailing fears of the time was that the Soviet Union would drop an atomic bomb somewhere over the United States (maybe even Canada,) obliterating a city and raining toxic radioactive ash over the surrounding hundreds of kilometres.

It wasn’t such a farfetched idea at the time. In October 1961, the Soviets detonated the “Tsar Bomba” over the Novata Zemlya archipelago in the Arctic Sea. It was the most powerful manmade explosion in history. The 27-ton thermonuclear device was about 1,500 times more powerful than the U.S. bombs that levelled Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In fact, the blast was stronger than all of the conventional explosives used in the entire second world war combined.

Naturally, the Soviets’ ability to instantly and completely destroy anything with a given 35 square kilometre radius spooked the United States and Canada. A terrifying edited excerpt from John M. Fowler’s book Fallout published in the Toronto Star detailed in ghoulish detail the catastrophic horror that awaited a city struck by an atomic bomb.

Buildings would be vaporized and their citizens incinerated or condemned to a slow and painful death. The fallout—the radioactive ash ejected by the explosion—would float on the wind, raining down toxic material over hundreds of kilometres.

“People themselves might become ‘missiles’—by being picked up and thrown about violently by the blast wind,”Fowler explained. “On the basis of studies made on dummies in Nevada bomb tests, Clayton S. White [a U.S. medical researcher who studied how nuclear blasts affect the human body] estimated that ‘human missiles’ would cause injuries to people over an area of up to 800 square miles.”

Even subheadings in the Star excerpt are startling: ‘millions of degrees,’ ‘yawning crater,’ ‘towering cloud,’ and ‘after its over.’

A year before a plane dropped the Tsar Bomba, the Canadian government under Prime Minister John G. Diefenbaker published “Your Basement Fallout Shelter: Blueprint for Survival No. 1.” In it, experts provided easy-to-understand, step-by-step instructions for how to build a bunker from readily available supplies that wouldn’t cost more than $500 to assemble.

“Should a nuclear war occur, the risk of radioactive fallout will be very widespread, and will endanger many of us in our homes, even though a long way from the bomb explosion,” wrote Diefenbaker in the foreword. “The shelter described in this booklet, although not affording protection against the blast of a nuclear explosion or the fires that may result, will provide good protection against the more widespread radiation danger.”

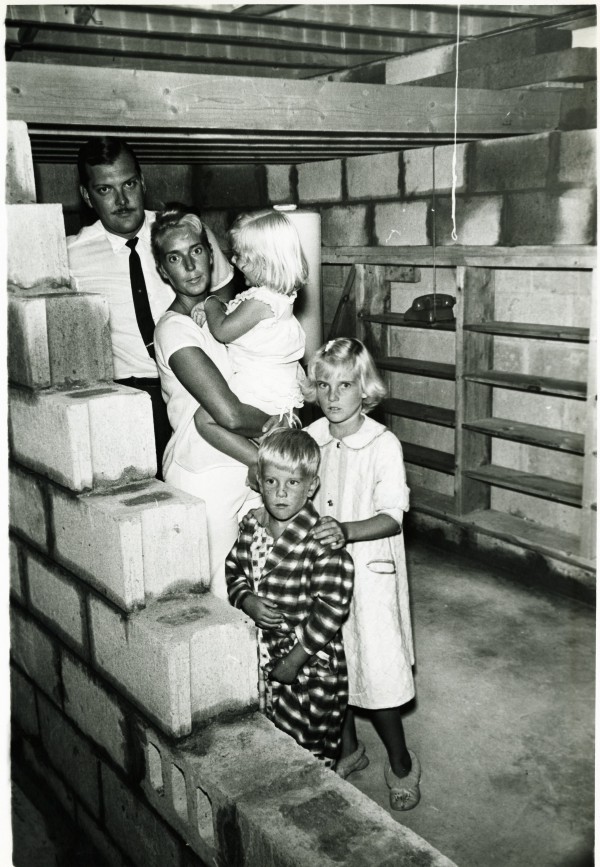

The 35-page booklet also explained when and how the shelter should be used, how to choose a site, and what materials to use (timber, concrete blocks, and mortar.) It also detailed life in the shelter: how to deal with the radioactive dust that might blow inside, how to avoid burning down the shelter down by not cooking with gasoline, and how to defecate into bags.

“Your only communication with the outside world, once you are in the shelter, will be by radio,” the text warns. “It is important that you check the reception in the shelter when you install it.” 250,000 copies were distributed during the first print run.

An example of the country’s official fallout shelter design was built at Queen’s Park, near the corner of University and College. It took member’s of the Emergency Measures Organization 70 to 80 hours to erect it out of the prescribed wood and concrete blocks, and almost immediately it became a focal point for vandalism and protest.

Ernest Tate, a 26-year-old stationary engineer, painted “Ban the Bomb” in brown paint across the south side of the shelter in July 1960. He was fined $50 but remained unapologetic in court, saying he’d just as soon do it again.

“I think we’re being pushed into this idea of a shelter, which is not adequate for a nuclear war. There is no protection in a nuclear war,” W. G. Dean, a lecturer and member of the University of Toronto’s Committee on Nuclear Disarmament, told the Globe and Mail later in the Tate story.

A month later, the Combined University Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament protested at the shelter on the 15th anniversary of the Hiroshima bomb. Later, 50 high school students carrying signs that read “moles we are not,” “civil defence is civil deceit,” and “the only defence is peace” picketed Queen’s Park.

Despite the protests, Prime Minister Diefenbaker said “each and all of us” should build a shelter. He took his own advice, too. A fallout shelter was built at 24 Sussex Drive by a government architect and a member of the Emergency Measures Organization. Toronto Mayor Nathan Phillips also built a shelter in the basement of his Oriole Parkway home, a move that was met with a barrage of criticism.

It was true: no fallout shelter could shield its occupants from the power of a nuclear explosion. Only blast-proof rooms and bunkers could do that. To that end, the Toronto alderman Fred Beavis suggested the city build bomb-strength holding areas for its citizens, but the idea came to naught. What the city did investigate, however, was the idea of using the subway lines and Nathan Phillips Square parking garage as mass holding areas in the event of nuclear fallout reaching the city.

Though no modifications were made to the final design, a report published in 1961 said special filters could be added to ventilation shafts, allowing in breathable air but keeping out radioactive dust. Only one of the parallel tunnels would be occupied, the TTC theorized, so that a service train could operate on the spare track, delivering supplies and moving the sick or injured.

Air raid sirens, six of which were built in Toronto (at least one still exists,) would sound out a warning, telling the people of the city to take cover at home or at the nearest subway station. About 35,000 people could be squeezed between Dundas West and Sherbourne stations, giving each person about 1 square metre of space.

Toronto and Canada’s nuclear preparations were tested later that year during a mock nuclear attack called Tocsin B. The exercise imagined what would happen if 12 major cities across the country were subject to a co-ordinated attack by surface-to-air nuclear missiles and bombs dropped from planes.

The results weren’t good. 2.2 million people would have died, including Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, with 1.5 million injured nationwide.

“Toronto in fantasy blew up at 10:45 last night,” the Globe and Mail reported. “In the fury of the explosion an estimated 630,000 persons were killed and 225,000 injured. No-one could estimate the deaths that would result from radiation poisoning.”

In Montreal, 900,000 imaginary people died. 142,000 were annihilated in Ottawa—more in cities from Vancouver to Stephenville, Newfoundland. “Windsor was razed by a 10-megaton bomb dropped on Detroit.”

Defence Minister Douglas Harkness watched with his cabinet from a cramped nuclear shelter in Petawawa, Ontario as the country was blasted into oblivion. Despite the shocking results, the acting prime minister looked on the bright side.

“If you lose 3,000,000 people it’s awful but there are still enough left to constitute a nation.”

One comment

I have one in my 1953 bungalow in Edmonton