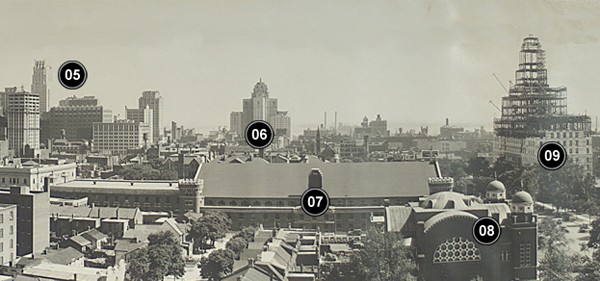

The summer of 1930. It was the beginning of a difficult decade for Toronto, along with much of the rest of the world. The Great Depression had just begun. But before the stock market crashed, the boom of the 1920s had fueled construction projects all over the city. Toronto was full of elegant new landmarks — many of them still familiar to Torontonians today: Union Station, The Royal York Hotel, Maple Leaf Gardens, The Palais Royale, The Sunnyside Bathing Pavilion, The Princes’ Gates… And on one July day, a photographer climbed to the top of a building on the north-east corner of University & Dundas, pointed a camera south, and took this photo of our city’s new skyline. It’s full of interesting details, so I thought I’d give a brief “tour” of some of the buildings you can see.

But first, you’ll want to open the full version of the image so you can see the whole thing, which you can do by clicking on it here:

By 1930, the Maclean family’s publishing empire was already more than four decades old. It had all started back in the 1880s with a trade journal called The Canadian Grocer. Before long, they’d added Maclean’s, Chatelaine and The Financial Post among other titles. They were the biggest publishing empire in the British Empire. And that meant they could afford to buy an entire block of land in downtown Toronto. On the north-east corner of University & Dundas, they built a whole complex to house their offices and printing presses. In 1930, the latest addition had just opened: the new Maclean Building soared a whole nine storeys into the air, making it the tallest building in the neighbourhood. That’s when a photographer climbed up onto the roof and snapped this photo of Toronto’s skyline.

Today, the building is still there. It’s on the north side of Dundas, just to the east of the intersection. On the corner itself, you’ll find a TD on the ground floor of the newer Maclean-Hunter Building; it was built in the early 1960s.

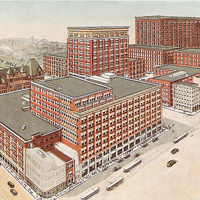

Of course, the Macleans weren’t the only Toronto family to build a wildly successful business. At about the same time the first edition of The Canadian Grocer was hot off the presses, Timothy Eaton was moving his famous department store to the corner of Yonge & Queen. Over the next few decades, as Eaton’s became a Canadian institution, the company bought up whole blocks of the surrounding neighbourhood. By the time this photo of the skyline was taken, they owned pretty much everything between Yonge, Bay, Queen & Dundas. In 1930, their complex sprawled over more than 60 acres: there was the main store, an annex store, factories, warehouses and mail order facilities. Today, that same huge chunk of land is home to the Eaton Centre.

Today, this is where you’ll find Nathan Phillips Square. But in 1930, the same spot was home to Toronto’s most notorious slum. What is now an open expanse of concrete was a warren of hovels back then, where slumlords crammed people into tiny, poorly-insulated shacks. The Ward had been home to one new wave of immigrants after another — stretching all the way back to the mid-1800s — and by the time this photo of the skyline was taken, it had become Toronto’s first Chinatown. These were hard days for those new Canadians: anti-Asian racism was rampant; the federal government had recently banned all immigration from China. The Great Depression would make things even worse.

By the summer of 1930, the days of The Ward were already numbered. Developers had begun to buy up parts of the neighbourhood to build office towers and hotels. Finally, in the late-1950s, the City expropriated the land, forced all the residents out, and demolished the buildings to make way for our new City Hall. Chinatown was driven west along Dundas to Spadina, where it is today.

Back in 1930, Old City Hall was still known as just plain old City Hall. And Toronto’s mayor was a newspaper reporter by the name of Bert Wemp. Just a few months earlier, he won the election by running against a plan to improve the downtown core. Huge swathes would have been rebuilt. There would have been grand boulevards slicing through the city centre, a majestic new square where Nathan Phillips Square is now, and a huge traffic circle near Union Station along with new Art Deco skyscrapers and public buildings. But after the stock market crashed, the public mood changed. And people in the suburbs had always felt the plan — which hoped to improve traffic congestion — did too much for downtown and too little for them. Wemp was elected. And in a referendum, the proposal was rejected by fewer than two thousand votes.

The Old City Hall building itself had already been around for thirty years by this point. It was designed by E.J. Lennox (the same architect responsible for Casa Loma, the King Edward Hotel and the west wing of Queen’s Park). Until the Royal York Hotel was built in the very late 1920s, nothing in Toronto reached higher than the tip of this clock tower.

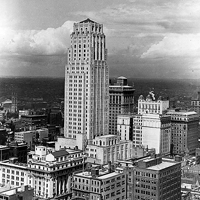

The Royal York didn’t spend long as the tallest building in Toronto, though. In the summer of 1930, the title belonged to this new skyscraper. In fact, it was the tallest building in the entire British Empire. Today, we call it Commerce Court North, but back then it was called the Bank of Commerce Building. It was brand new — it opened the very same year the photo of the skyline was taken — and it was designed by the architectural firm of Darling & Pearson (who also built many of Toronto’s other landmarks: like the original ROM, the AGO, and 1 King West). On the 32nd floor, it had the most spectacular observation deck in the city, decorated with four enormous, bearded heads. It would remain the tallest building in Toronto for the next three decades, until Ludwig Mies van der Rohe built the sleek black modernist towers of the Toronto-Dominion Centre in 1967.

In 1930, the Royal York was brand new, too, just a year old. Back then, it was the biggest hotel in the British Empire. It had ten elevators, the biggest pipe organ in the country, a shower and a bath and a radio in every single one of its 1000+ rooms, and a telephone system so extensive they needed three dozen operators to run it. In fact, the Royal York is so fancy that nearly a hundred years later, the Queen still stays there when she comes to town.

Once upon a time, this was one of the most impressive buildings in all of Toronto — in all of Canada even. The Armouries were built in the late 1800s as a training ground for the militia. It was the biggest building of its kind on the continent. It looked like a huge, squat castle, complete with turrets and flags. Inside, you’d find a rifle range, drill halls and even a bowling alley. This is where Torontonians lined up to volunteer for the Boer War, the World Wars and the Korean War. They were trained here, too. But in the early 1960s — about the same time The Ward was being leveled to make way for our new City Hall — the Armouries were demolished to make room for the new provincial courts that still stand on this same spot today.

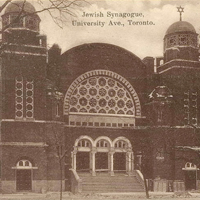

In 1930, The Ward was best known as Toronto’s Chinatown. But thirty years earlier, it was most notably Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who called the neighbourhood home. It was back then — in the very early 1900s — that the local congregation opened this beautiful new synagogue on University Avenue (just a block to the north of the Armouries). Inspired by the design of England’s Westminster Cathedral, this synagogue became the spiritual centre of Toronto’s Jewish community. It stood on this spot for fifty years before it was demolished. By then, the community had moved west: the Goel Tzedec congregation merged with the worshipers of the Beth Hamidrash Hagadol Synagogue on McCaul and opened the brand new Beth Tzedec Synagogue on Bathurst Street between St. Clair & Eglinton.

Today, the Canada Life Building — topped by its familiar weather beacon — is one of our best-loved landmarks. But in the summer of 1930, it was still being built. The Beaux-Arts skyscraper would serve as the headquarters for Canada’s biggest and oldest insurance company: Canada Life. (They still own the building, though they were recently swallowed up by Great-West Life.) It was supposed to be just the first in a whole complex of buildings along University Avenue, but the Great Depression forced them to cancel those plans.

The helpful weather beacon (lights run up or down according to the changing temperature, flash red or white for rain or snow, steady red for clouds and green for clear skies) was added in the 1950s.

10 The Chestnut Trees of University Avenue

10 The Chestnut Trees of University Avenue

Today, University Avenue is a canyon of concrete, pavement and glass. But less than a hundred years ago, it was a majestic tree-lined boulevard. In the early 1800s, five hundred horse chestnut trees were planted along either side of the road and a grassy promenade was built down what is now the centre of the street. It became one of Toronto’s grandest avenues. Even Charles Dickens was impressed when he came to town in the 1840s.

Over here, in the west, you can see the towering spire of one of Toronto’s oldest churches. St. George The Martyr had been built at the edge of what’s now the Grange Park all the way back in the 1840s. The population was booming; Toronto’s very first church — the Anglicans’ St. James — just wasn’t big enough anymore. When St. George was built, it became one of the most easily recognizable landmarks in the city. The spire stretched a hundred and fifty feet into the air. It could be seen all the way from the lake. Ships used it to navigate. But sadly, the church suffered a terrible fire in 1955. Most of the building — including the slender spire — was destroyed. Today, only the brick tower that supported the spire is left standing. And a new church, with new gardens, has been built on the same spot.

Take another tour of 1930s Toronto here.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more sources, images, links and related stories there.

Original photo of the skyline via Wikimedia Commons.