First Canadian Place has been the tallest skyscraper in Canada for four decades now. At 298.1 metres from sidewalk to rooftop, the brilliant white tower is certainly an impressive feat of engineering, but what First Canadian Place delivers in height it lacks in physical presence and allure.

Maybe it’s the relatively unadorned, geometric shape of the building, or perhaps it’s because the CN Tower, completed just a year later in 1976, trumps it on a technicality as the tallest “freestanding structure” in the country. Whatever it is, FCP rarely figures in the conversation about Toronto’s most beloved buildings.

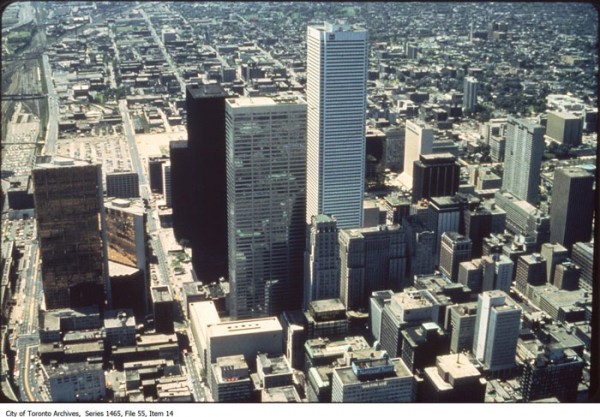

The Bank of Montreal’s Ontario headquarters was a relative latecomer to the downtown office tower scene. Announced in October 1972 by developer Olympia and York, the First Bank complex (as it was originally known) swept away the historic headquarters of both the Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail, and razed a historic Bank of Montreal office, too.

Olympia and York were lucky to get building permission when they did. A few months later, in December 1973, Toronto city council passed an interim bylaw capping all new downtown construction projects at 14 metres and 3,700 square metres. The move was a temporary measure designed to give planners a chance to reassess the merits of allowing high-rise office development in the heart of the city without residential space to balance it all out.

“The planners are thinking in terms far beyond esthetic considerations of sunlight, open space, and trees beside buildings,” wrote Graham Fraser in the Globe and Mail when the bylaw was passed. “They are rethinking what the downtown is used for.”

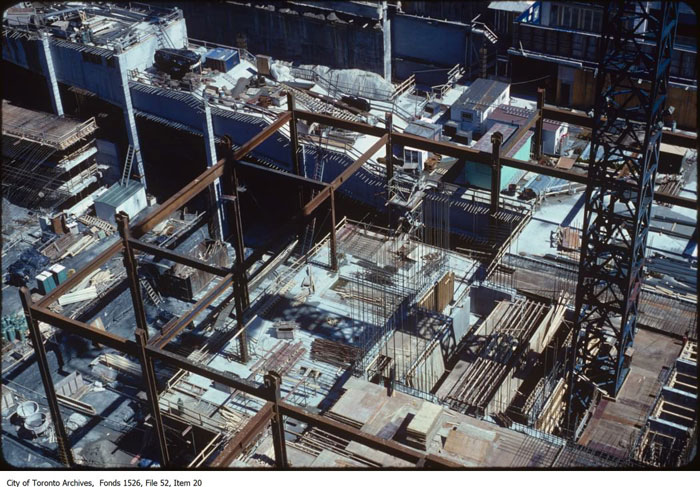

The First Canadian Place basement was excavated and the steel skeleton of the building started to rise in the last weeks of 1973. A two-storey walkway was erected around the construction site to allow curious onlookers the chance to peek in without creating a logjam on the sidewalk.

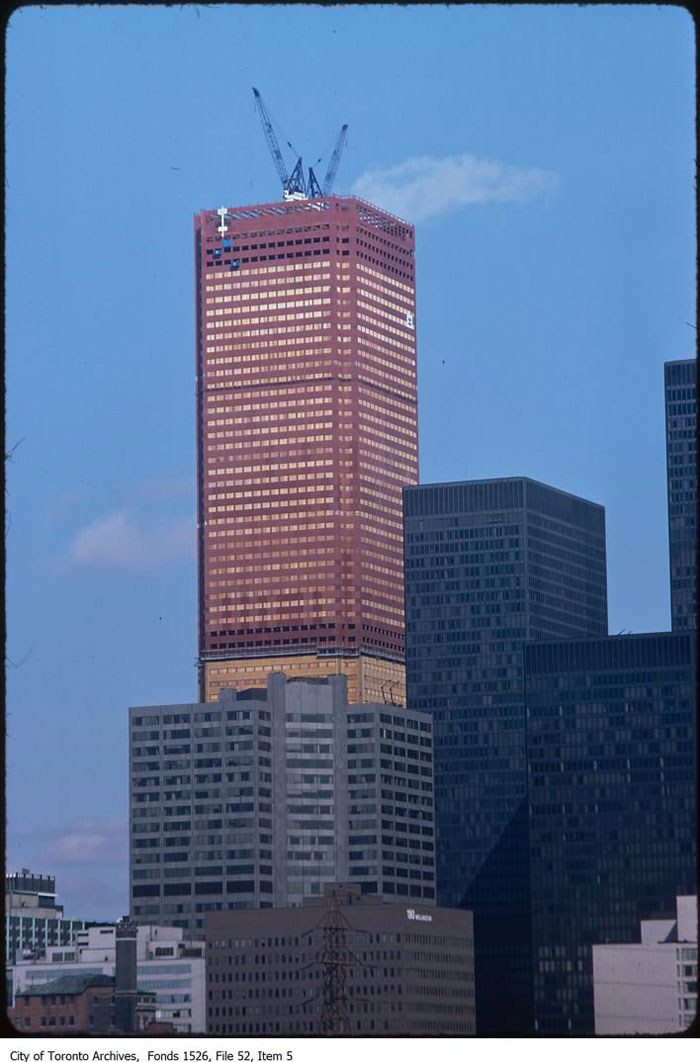

Interestingly, the developers opted to break the tower into four zones, treating each one as though it were a separate building. The lower stories were completed and the first and tenants began to move in while the upper levels were still a steel frame. Each section had its own bank of double-decker elevators, which allowed construction workers to ferry materials up the core of the building with minimal disruption.

The unusual elevator arrangement benefits the tower today: By stacking the cars on top of one another, office workers on even numbered floors board on a different level to their odd-numbered counterparts. This innovation reduces crowding during the morning and afternoon rush hour, when some 20,000 people move in and out of the building.

First Canadian Place became the tallest office building in Toronto and Canada on January 13, 1975, when steelworker Gerry Deschamps bolted the first horizontal structural beam higher than the roof of Commerce Court. Though construction generally progressed as expected, there were hiccups. A $150,000 shipment of normally crisp white Carrera marble cladding from Italy had “too much grey in it” and had to be replaced.

The first tenants, staff belonging to Bank of Montreal, moved into the ground floors in July 1975 and the building was fully occupied by December. The stats themselves were astounding: 45,000 tons of steel, 113 kilometres of piping, 680,000 kilos (37,300 square metres) of glass, and 4,400 tons of marble went into making the tower, according to a promotional newspaper supplement printed in the summer of 1975.

Albert Reichmann, one of the co-founders of Olympia and York, called his company’s tower “a triumph of open space and nature.” The author of the supplement wrote that the 17-acre site was previously populated by small shops and dingy lanes. “Not a blade of grass, a flower, a tree, a bench, or inviting public could be found within that vast block.”

Olympia and York hoped the podium would become a magnet for shoppers and diners, perhaps even a tourist attraction in its own right—a “people’s place.” Perhaps they miscalculated the level of affection the people of Toronto would have for the office, because it has never been a place the public has chosen to linger en masse.

Maybe because it lacked a compelling draw, like an observation level, spaces both TD Centre and Commerce Court offered until 1977, Torontonians never became properly acquainted with their world class skyscraper in the years that followed. Today, most people experience the country’s tallest skyscraper gliding by on a King streetcar or via the basement, which is part of the PATH network.

The tallest towers in major cities across North America usually have some sort of public component. The Willis Tower in Chicago has the Skydeck, Los Angeles’ U.S. Bank Tower is getting a 70th floor lookout, and One World Trade Center is opening its observation level, the One World Observatory, at the end of the month. That First Canadian Place doesn’t have something similar is really the fault of the CN Tower, which pretty much eradicated the appetite for building owners to open their top floors to the public.

The result will be that when the Frank Gehry and Foster + Partners-designed towers planned for King West and Yonge and Bloor ultimately take over the top spot, there won’t be many people mourning the deposed ruler of the skyline.

First Canadian Place: the skyscraper Toronto never got to know.