Between 1931 and 1939, the construction at Rockefeller Center in New York City was a magnet for curious onlookers. America was mired in the depths of the Great Depression, and some 75,000 people were employed on the 12-acre site, laying foundations and assembling the steel skeleton of the largest private construction project in the history of the great metropolis. Countless others, either out of work or on reduced hours, looked on from the sidelines.

There were so many people lurking outside the construction barriers that J. D. Rockefeller, the impossibly rich founder of Standard Oil and the project’s backer and namesake, built a covered shed overlooking the work site, shielding the the people the papers called “kibitzers of construction” from the elements and falling debris.

Best of all, Rockefeller set up an official “sidewalk superintendents” club. On November 7, 1938, 10,000 membership cards bearing the motto “De beste stuurlui staan aan wal”—”The best pilots stand on the shore”—were issued to the men, women, and children crowded by the side of the construction site.

On the back was a list of tongue-in-cheek sidewalk superintendent club rules: take off your hat, don’t drop kids over the fence, and make all autograph requests in writing. There’s even video of the club in action:

In Toronto, visitors to the Bank of Montreal headquarters under construction at King and Bay were demanding similar treatment.

In July, 1939, the Globe and Mail reported how “patrons of the steam shovel as a medium of art” were being forced to peek through knotholes in construction hoarding in order to catch a glimpse of what was going on inside. The accompanying photos show men straining to see through tiny gaps in the fence or peer over the top.

“The real dyed-in-the-wool refuse to succumb to the to the defeatism of the lay public, which usually passes right by when the lack of accommodation for spectators becomes apparent,” the story explained.

In 1947, the Globe and Mail clarified an important difference between sidewalk superintendents and mere “kibitzers.”

A superindendent, wrote columnist Billy Rose, “watches a gang of men digging a hole in the ground and is satisfied.” A kibitzer, on the other hand, “waves his hand at the gent behind the crane and advises: ‘A little to the right, buddy. Let her down easy now.'”

“Most sidewalk superintendents rate a kibitzer two notches lower than the peeping tom.”

Sidewalk superintendents were typically male white collar workers employed in the burgeoning financial district. “A man who can’t change a washer on a tap gets a vicarious thrill out of watching these tons of steel girders being shoved in to place,” wrote Frank Tumpane, also in the Globe and Mail (their coverage of this topic was excellent.)

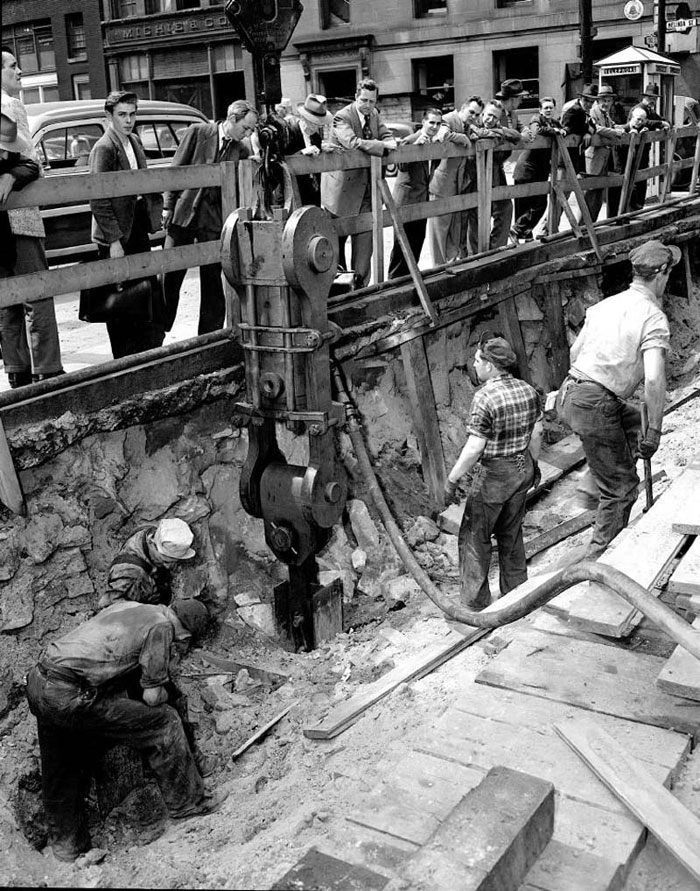

“The downtown section of Toronto is swarming … what with all the building in progress,” Tumpane said. “You can hardly move a block without bumping into half a hundred of them with their backs lined up against a wall watching a crane, or their noses shoved over the edge of an excavation scanning a steam shovel.”

The Bank of Nova Scotia offices were a prime target in 1947, but superintending reached its zenith with construction of the Yonge subway line in the early 1950s.

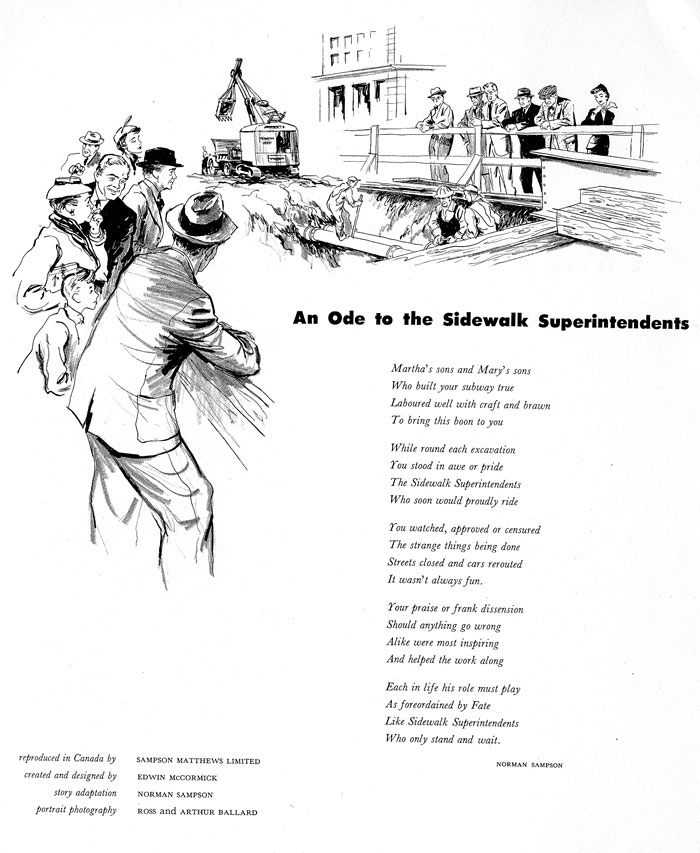

The level of curiosity in the mostly cut-and-cover excavation was so great that the TTC set up special viewing areas overlooking the trench and even issued special sidewalk superintendent manuals. There were five of them in the series, explaining the methods of construction, charting the line’s progress, and finally telling wide-eyed riders how to ride the new subway.

At other construction sites developers were realizing that catering to sidewalk superintendents was a cheap way to generate positive PR. Peepholes in wooden siding became windows, and projects that involved deep excavations sometimes installed balconies directly over the pit.

Proctor and Gable hung artwork by local Deer Park kids on the hoarding surrounding their 21-storey office project at Yonge and St. Clair in 1963, and over in Montreal the Canadian Lumbermen’s Association put up a wooden observation tower at the Expo 67 site in 1965.

During the late 1960s, however, the supers of Toronto appeared to be losing their passion for construction.

Perhaps burned out by decades of clanging steel and rumbling excavation, newspapers reported fewer eyes at the peepholes. “Torontonians have become so bored by their building boom that they hardly ever even seem to bother to raise their eyes skyward any more,” wrote journalist Bruce West.

There was a brief revival in the 1970s, however. The builders of Commerce Court West installed a box over the five-storey foundation pit at King and Bay in 1970. A recording, updated weekly by project engineer Hugh Griffiths, explained what people could see from their vantage point via a loudspeaker.

“Anybody could go out and dig a hole and put a barricade around it and six people would show up to look at it,” Griffiths said. “There’s a certain amount of pride in seeing the development and people like to hear the superlatives.”

In 1974, the builders of First Canadian Place put up a two-storey scaffold around their construction site, separating those who wanted to linger from the workers scurrying to the office.

Some developers do still make an effort to cater to sidewalk superintendents, usually in the form of little windowlets, but too often downtown construction sites are kept hidden from curious onlookers.

There’s certainly an appetite for behind-the-scenes access as the popularity of Metrolinx’s late-night tunnel boring machine party in April proved.

Perhaps it’s time to bring back the membership cards.

2 comments

Safety equipment? What’s that? And the traffic cops actually controlled the traffic.

Nowadays, there’s also live construction cameras that can be viewed online – perhaps the new generation.

For example: http://www.ucitonline.com/uoftlaw/click2stream.html