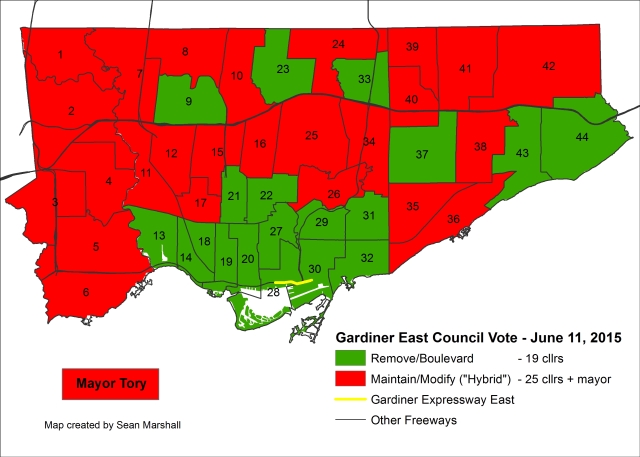

Immediately after that vote, I created the two maps below. The first shows the vote on whether to go with the less expensive option, to replace the East Gardiner with a boulevard. The second shows the final vote on the “hybrid” option strongly supported by the mayor, despite all the evidence that maintaining that portion of the elevated freeway wasn’t necessary. I shared these maps on Twitter.

Vote on the Remove/Boulevard option for the Gardiner East

Vote on the “Hybrid” option for the Gardiner East

While all “downtown” councillors, representing nearly all the former City of Toronto and much of East York favoured the tear-down, it wasn’t entirely an urban-suburban split. Six councillors in Scarborough and North York, namely Paul Ainslie, Michael Thompson, Ron Moeser, Shelley Caroll, John Filion, and Maria Augimeri, voted for the Gardiner’s removal. Eight (including Perruzza and Ford) voted against the Mayor, making the decision to go with the “Hybrid” a close 24-21 vote, a blow to Tory’s promise as a reasoned “consensus builder.”

But almost as troubling as the vote, I soon started to notice mentions and replies to my Twitter feed calling for de-amalgamation. Here is a sample:

Eesh! Can we talk de-amalgamation? RT @Sean_YYZ: Map of the#TOcouncil vote on the fate of the #GardinerEast#TOpolipic.twitter.com/Thj4hYyemm — Sheryl Kirby (@sheryl_kirby) June 11, 2015

Umm…can we get a divorce? If ever proof was needed that this city post-amalgamation is a failure, here it is! https://t.co/pbwjfMM8lF — NaTck33 (@NaTck33) June 11, 2015

Hooray for amalgamation. https://t.co/SWzcBPP6hN— Cassandra Fulgham (@cfulgham) June 11, 2015

These reactionary responses, while understandable, ignore some inconvenient truths.

It’s easy to forget that Gardiner Expressway, along with the Don Valley Parkway and the Allen Road (the completed section of the infamous Spadina Expressway), were built by Metropolitan Toronto, an upper-tier government that was created by the province in 1953 in order to accommodate and control Toronto’s rapid growth. Its boundaries were the same as those of the post-1997 City of Toronto.

Metro Toronto was given the responsibility for many, including the TTC, all major roads, ambulances, police, most of the city’s public housing, waste collection, and the administration of social services. Metro had its own system of parks separate from the lower-tier cities and boroughs, and its own divisive politics. The Gardiner Expressway, one of Metro Toronto’s first mega-projects, was named for the first Chair of Metro Council, Frederick G. Gardiner. The old City of Toronto opposed Metro’s Spadina Expressway plans; it was the Province of Ontario that stepped in to stop the controversial freeway at Eglinton Avenue.

Had Mike Harris’ PC government wasn’t elected in 1995 and the six cities and boroughs were never amalgamated, it would be a Metropolitan Toronto Council deciding the Gardiner’s fate, and we’d probably still see the same urban/suburban divide when it came to the final vote.

The case for amalgamation

I’ll come right out and say that the provincial government under Mike Harris made a terrible mistake when it decided, without warning, to amalgamate Metro and its six lower-tier municipalities into a megacity in 1997. Even though I lived in Brampton at the time, I opposed Bill 103 when it was introduced and enacted in 1997. But I think amalgamation was a mistake because the process was rushed, it was steamrolled over the objections of almost every local politician and engaged citizen, and the motivations were politically suspect – a left-leaning City of Toronto, led by an NDP-allied mayor was overwhelmed by a more Conservative-friendly suburban population, with Mel Lastman as the first mayor.

The first few years were painful as departments and agencies were melded together. Mayor Lastman’s property tax freezes did not help when the need for city services was growing. But what amalgamation did do was provide taxation and service equity across Toronto. York, the poorest of the six lower-tier cities, did not even have a full-service recreation centre and had a relatively poor parks and library system. That all changed, and generally, for the better.

The Toronto Public Library, which just opened its 100th branch, is the the envy of library systems around the world. It is the second largest system in North America (after New York’s) and has the highest circulation. When its budget was threatened in 2011 in the early days of the Ford administration, they had to back off due to an overwhelming public campaign.

New Scarborough Civic Centre Branch, photo by W Poon

I would argue that the TPL makes the best case for amalgamation. Before, each of the six cities had their own library systems, and the Toronto Reference Library was a separate entity. Library access and budgets were limited in some of the smaller systems, especially in York and East York. Amalgamation of the library system has created a more equitable system that’s the envy of the world. It has been expanding and renovating branches all across the city without any cries of regional favouritism. While the library system is still mostly a collection of reading materials, the TPL has adapted to the digital age, providing communal study spaces, media labs, new computer equipment and 3-D printers, and access to vast digital resources through its website, including current periodicals. The Toronto Public Library is something all Torontonians should be proud of.

So yes, there will often be an urban/suburban split on some issues, particularly on transportation items. I share the frustration after last week’s vote. We particularly need to elect a better council in 2018. And there always improvements that can be made to make this city work better for its diverse neighbourhoods, perhaps devolving more responsibilities to reformed community councils.

But I have little time any more for calls for de-amalgamation. It won’t change politics all that much. Let’s focus on making this city work.

Cross-posted from Marshall’s Musings, Sean’s personal blog

2 comments

It sticks with me from Politics 201 at U of T that Aristotle said humans are urban creatures. (well… political… but the prof explained “political” as meaning from the polis). We do our best being when we live in cities.

The megacity has been a boon for the inner suburbs. As property values invert, and wealth moves downtown while the bedroom communities fester, it is a good thing that the experience and infrastructure a city develops with age and maturity already exist for the younger portions of the city to benefit from. If the trend continues, and in 40 years it’s York region falling apart… they won’t have the benefit of an experienced municipality, programs and staff, that have been there, and watched neighbourhoods go sour, or spring back to life. The library system is a good example of this.

But, Sean, I think your piece misses something that was lost in the Megacity: and that’s the sense of urban destiny or control for a small little area. By slushing the politicians who serve on the local councils with the politicians who serve on the greater council, everything is a power struggle and an expression of identity. There are no entry level positions to politics in Toronto, where you can focus on the small communal good and be modest and moderate in your achievement.

The formal political structure feels increasingly poisoned to me in the city.

The Toronto Public Library is really the shining example of where amalgamation worked, and I doubt few would want to go back on that. I figure having one rather than six fire departments also makes sense. The nearest fire station to a fire in East York may have been located in Scarborough, for example. And yes, transit and major roads were already consolidated under the old Metro government, and those tend to be where the disagreements lie.

De-amalgamation of the school boards might be a good thing. And perhaps the four community councils would benefit from having more discretionary powers (and budget) under directly elected chairs. The local identities still smoulder under the surface of “one big city,” and these differences could be better accommodated at a more local level. I’m basically advocating a “four borough” arrangement.