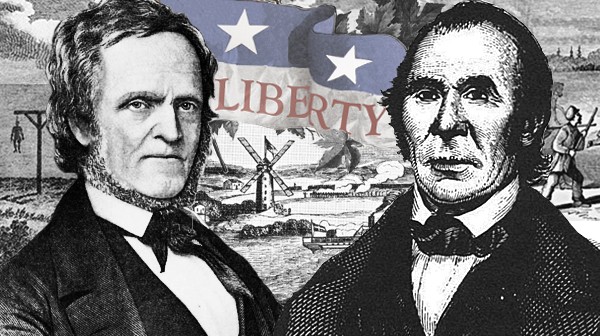

William Lyon Mackenzie ran for his life. His rebellion had failed. It was a disaster. His rebel army was crushed on Yonge Street. His headquarters at Montgomery’s Tavern were burned to the ground north of Eglinton. Some of his men were already dead. Others would soon be hanged for treason. Just a few years earlier, Mackenzie had been the first Mayor of Toronto. Now, he was the city’s most wanted fugitive. The Lieutenant Governor was offering a £1000 reward for his capture. So Mackenzie was forced to flee the city he loved, smuggled through the countryside by his supporters as gangs of angry Loyalists searched for him. He ran all the way south to Niagara, getting rowed across the river just a few minutes ahead of the men who had come to arrest him. He was lucky to escape Canada with his life. He would spend the next decade living in exile.

But Mackenzie wasn’t ready to give up. Not yet. His failed rebellion in Toronto was just the beginning. Now, he and his supporters would launch a war against the British government in Canada, hoping a series of bloody border raids would spark a full-scale democratic revolution. It would last a year — for pretty much all of 1838. We call it the Patriot War.

And the rebel’s admiral in that war was a man by the name of Pirate Bill Johnston. He was a smuggler, a spy, a veteran of the War of 1812 on both sides and, weirdly, an IRS agent. The rebel mayor was the most wanted man on the western shore of Lake Ontario. But the pirate admiral Bill Johnston would soon be the most wanted man in the east.

He’d been born in Trois Rivières, but he grew up just outside Kingston. And it was there that he would make his name as a young smuggler. By the time he was in his early 20s, Johnston was the captain of his own ship. He sailed his schooner through the labyrinth of islands at the spot where the St. Lawrence River meets Lake Ontario. We call them the Thousand Islands — but there are actually almost two thousand of them. It was the perfect spot to be a smuggler. Johnston would make runs through the confusing warren of islands, bringing contraband goods across the river from the United States. And he wasn’t alone. Some estimates say that as much as 90% of all the tea in Upper Canada had been smuggled into the province to avoid paying taxes — and plenty of the rum, too.

Still, while Johnston might have been a smuggler, he was also a loyal British subject and Canadian. That is, at least, until the War of 1812.

When the Americans first invaded, Johnston fought on the Canadian side. But he’d never been very good at following rules: he clashed with his superiors so much that he eventually beat one of them up and got tossed in jail for a time. Meanwhile, he’d also developed a soft spot for the ordinary American citizens who were being held in Canadian prisons during the war. He kept bailing them out and smuggling them back across the border so they could go home to their families. That landed him in jail again. The Canadians accused him of being a spy.

This time, he’d had it. Pirate Bill defected. Once upon a time, his own parents had fled from the United States — they were Loyalist Americans driven from their homes for taking the British side in the American Revolution. Now, their son headed in the other direction. He climbed into a canoe with a few American refugees and rowed himself all the way across the lake to the American naval base at Sackets Harbor. There, he found the man in charge of the United States’ fleet on Lake Ontario — Commodore Isaac Chauncey — and pledged himself to the American cause. Now, Pirate Bill would fight for the stars and stripes.

Johnston spent most of the next two years fighting against the British and the Canadians in the Thousand Islands. He waged war in a big rowboat armed with a cannon, a vessel light enough that he and his men could slip through the islands more easily than the big warships, striking quick like lighting and then evading capture. Pirate Bill would witness some of the most famous moments in the entire war, including the Battle of Sackets Harbor and the failed American invasion of Montreal that ended in disaster at Crysler’s Farm. By the end of the war, it seems that he had earned a reputation as a notorious pirate — at least as far as the British were concerned.

After the war, Johnston went back to his old job: smuggling tea and rum into Canada. But now, he did it from the American side. And he also worked for an early precursor of the Internal Revenue Service, spying on Canadian smugglers for the United States government. For the most part, the next twenty years were quiet ones for Pirate Bill. He grew into middle age, raising his family on the American banks of the St. Lawrence, just across the river from his old stomping grounds in Canada.

And then came Mackenzie’s rebellion.

Johnston was in his late 50s by the time Toronto’s rebel mayor marched his army down Yonge Street. But Pirate Bill followed news of the events from far on the other side of Lake Ontario. He heard of the rebellion and of Mackenzie’s escape to the United States. There, the rebel mayor immediately set to work rallying supporters, giving speeches, raising money, collecting guns and ammunition, getting ready to launch his new war in the name of democracy.

Just a few days after his harrowing escape across the border, William Lyon Mackenzie and his supporters seized an island on the Canadian side of the Niagara River — Navy Island, just above Niagara Falls — and declared themselves to be the provisional government of the new Republic of Canada. They even had their own flag and currency. The Patriot War had begun.

The first major incident happened just a couple of weeks after that. The rebels on Navy Island were being supplied by an American steamship called the SS Caroline. One winter night, a band of Loyalists snuck across the river, attacked the ship, forced her crew off the boat, set her on fire, and watched as she floated down the river, sinking as she burned. Charred chunks of the vessel plunged over Niagara Falls.

The burning of the Caroline sparked a diplomatic crisis. It was, for many Americans, an absolute outrage — reason enough to declare war on Canada. The Caroline was an American ship in American territory. One of the crew members — a Black man by the name of Amos Durfee — had been shot dead, his body left on the dock. His corpse would be carried to Buffalo and displayed outside the Eagle Tavern as a recruiting tool for Mackenzie’s new war. Durfee’s body, one reporter wrote, “was held up — with its pale forehead, mangled by the pistol ball, and his locks matted with his blood! His friends and fellow citizens looked on the ghastly spectacle, and thirsted for an opportunity to revenge him.” Newspaper accounts of the battle, grossly inflating the death toll, made things even worse.

“The loyalist troops,” the New York Herald cried, “have made an assault upon our territory. They have murdered in cold blood our citizens. They cannot escape our vengeance… Niagara’s eternal thunders are sounding their requiem! and from the depths of that mighty flood come the wails of their spirits, calling for the blood of their murderers!”

Few were as angry as Pirate Bill Johnston. Soon, he was in Buffalo himself, meeting with Mackenzie and other rebel leaders at the Eagle Tavern. He was joining their war. Mackenzie named him the Admiral of the Patriot Navy in the east. Of course, they didn’t actually have a navy, but they weren’t about to let that stop them.

They would start with an attack on Fort Henry in Kingston. It seems to have been Pirate Bill’s idea. It would be a huge victory if they could pull it off, seizing the biggest military base in the province. But it would be difficult. One force would attack Windsor as a distraction in the west. Another, led by Pirate Bill, would head to the Thousand Islands and attack Gananoque as a distraction in the east. The main force would gather on Hickory Island, not far from Kingston, ready to march across the ice of the frozen St. Lawrence and launch the final attack.

The day they picked to begin their operation was February 22 — George Washington’s birthday. They spent the next few weeks getting ready. In towns across upstate New York, American volunteers and exiled Canadians trained to fight. Pirate Bill and the Patriots broke into military depots and stole thousands of guns — sympathetic American guards simply melted away. Some of the weapons were smuggled into Canada, into the countryside around Kingston, where hundreds of rebel supporters secretly waited to join the attack once the invasion had begun. At least one spy inside Kingston fed the Patriots information and was ready to act on the fateful day.

But things didn’t get off to a very good start. The attack on Windsor quickly failed. And in the Thousand Islands, the Patriot rebels were having trouble keeping their plans a secret. A young teacher from Gananoque — Elizabeth Barnett, hailed as the Laura Secord of the Patriot War — caught wind of the invasion while she was visiting family on the American side of the St. Lawrence. She rushed back home to Canada to warn the authorities. And by then, the authorities already had their own suspicions. They were building defences. Holes were being cut in the ice. Mohawk reinforcements were called in. The spy was unmasked and sent into exile. Suspected rebel sympathizers were warned: they would be killed if they so much as left their houses.

Still, it was the name “Pirate Bill” that sparked the most fear. “When [Elizabeth Barnett] mentioned Bill Johnston’s involvement,” the historian Shaun J. McLaughlin writes on his great Pirate Bill Johnston blog, “the townsfolk had fits. Women and children fled to the country for safety. Men gathered their weapons. Couriers rode at a gallop to Kingston, Brockville, and other towns to spread the warning.”

Meanwhile, on Hickory Island, the rebels were gathering. But it wasn’t going well there, either. It was the dead of the Canadian winter. The temperature had plummeted to -33ºC. And the Patriot General in charge of the attack — the awesomely named Rensselaer Van Rensselaer — was a drunk who doesn’t seem to have inspired much confidence in his men. More than a thousand began the trip, but only a few hundred ever made it to Hickory Island. In the end, Van Rensselaer turned around and went home. He never even started his attack.

It was a devastating blow to the rebels. And things only got worse from there. By now, the Patriot leaders were beginning to turn on each other.

Mackenzie blamed the failure at Hickory Island on Van Rensselaer’s alcoholism and incompetence. Pirate Bill agreed. “If Mackenzie or any other decent man had been at the head,” he said, “they would have taken… Kingston.” And Van Rensselaer was no fan of Mackenzie’s either. He called the rebel mayor a “meddling craven” and “a cruel, reckless, selfish madman… the greatest curse of the cause he pretends to espouse…”

But their disagreement was about more than just personal hatred. It was a symptom of a growing split in the movement — between the Canadian Patriots and their American allies. Van Rensselaer was an American. (He was from one of the most powerful families in New York State: his grandfather had signed the Declaration of Independence; his uncle was one of the richest Americans ever.) And the Americans were having more and more influence over the Patriot War. They even created a secret society — the Hunters’ Lodge — to support it. Tens of thousands of Americans joined; some estimates put the number as high as two hundred thousand. They were all promised free farmland in Canada once the war was won. Many of the soldiers who volunteered to fight with the rebel mayor and his pirate admiral were members of the Hunters’ Lodge. It made Mackenzie uneasy. What had begun as a Canadian rebellion against their British overlords was beginning to look more and more like an American invasion of Canada.

It was also beginning to look more and more like a failed invasion. A couple of weeks after Hickory Island, Van Rensselaer launched another attack: this time his men seized Pelee Island in Lake Erie. But the Loyalists fought back. By the time the dust had settled, the rebels were defeated and Van Rensselaer was dead.

Meanwhile, things weren’t going any better on the war’s other front. Mackenzie’s rebellion wasn’t the only democratic uprising in the Canadian colonies that winter. At the same time he’d been marching his army down Yonge Street, his allies in Québec had been fighting their own battles against the British government there. They too had been driven into exile in the United States; Mackenzie had been coordinating with them as they launched their own border raids into Canada. But they didn’t seem to be having any more success than the rebel mayor was.

Mackenzie was finally losing faith. War didn’t seem to be getting him anywhere. Over the spring and summer of 1838, the rebel mayor’s thoughts began to turn to peace. He moved to New York City where he launched a newspaper called Mackenzie’s Gazette. At first, he used it to support the Patriot violence. “One short war well managed might give this continent perpetual peace,” he argued. “Until Canada is freed the revolution in America will not be complete.” But by the end of the summer his tone had changed. Now, Mackenzie was arguing in favour of a bloodless, political solution to the problems in Canada.

Johnston felt betrayed. But even with Mackenzie gone and Van Ransselaer dead, Pirate Bill fought on.

His next move: he would finally find himself a navy.

Late one stormy May night, a Canadian steamship carried her passengers through the Thousand Islands on her way west to Toronto. But the Sir Robert Peel wasn’t alone in those choppy waters. She was quietly being followed by a pair of rowboats. It was Pirate Bill. He was in command of at least twenty Patriots, some of them — just like the American rebels at the Boston Tea Party — were disguised in a crude parody of First Nations clothing. They had come to steal the Peel and then use her to steal a second ship. Between them, the two vessels would be the beginning of Pirate Bill’s rebel fleet.

It wasn’t a random attack: the ship was owned by members of the Family Compact. They were the powerful, pro-British, Tory elites whose anti-democratic policies had sparked Mackenzie’s rebellion in the first place. They were the enemy.

When the Peel finally pulled into port to pick up more wood for her boilers, Pirate Bill and his men were ready. They landed a few hundred meters away and crept through the dark forest, getting ever closer to the Canadian ship. Finally, letting their war cries fly, they rushed from the darkness, raced across a clearing, and charged up the gangplank onto the decks. They quickly seized the vessel, forcing the crew and the groggy passengers back onto land at gunpoint. It was easy. Almost no one put up any resistance — there was one fistfight and that was it. The ship was theirs.

Johnston was now expecting more rebels to arrive. In fact, he was counting on them — none of his men knew how to run the boilers on a steamship. So he waited. And waited. But they never came. In the end, he had to abandon his original plan. Instead, he ordered his men to set the Peel ablaze.

As the rebels lit the flames, they cried out: “Remember the Caroline!”

Pirate Bill finally had his revenge. But now, he had really pissed people off. And not just his enemies. As Johnston hid in a cave in the maze of the Thousand Islands, both the Canadian and American authorities launched massive manhunts.

Still, even in hiding, Pirate Bill was a thorn in the side of the Family Compact. He published a proclamation of war from his island hideout. “The object of my movement is the independence of the Canadas,” he declared. And all the while, he kept trying to raise money and find guns for his men. “I will warrant,” he promised one potential supporter, “that they shall kill four times their number of Tories and give you their scalps if you shoud whant them.”

Once, when Johnston was spotted by a passing ship, he couldn’t resist chatting with some of the starstruck passengers. “One thing you may rest assured of,” he told them, “I will never be taken alive… Whoever comes after me must bring his own coffin…” As the ship sailed off into the distance, one of the passengers saluted the rebel by flying a handkerchief in the breeze. Pirate Bill responded by unfurling the flag of the Sir Robert Peel.

“Bill Johnson [sic],” said one of his greatest enemies, “laughed at the efforts of the Governor and all the authorities.” The pirate admiral made narrow escapes: racing through island forests under a hail of musket balls, slipping out of Loyalist traps, flaunting his nerve by throwing a huge party just before abandoning one hideout for another. His daughter Kate, who smuggled him supplies, became a celebrity in her own right. She was famous for her uncanny ability to evade the authorities. People started calling her the Queen of the Thousand Islands.

But the Patriot War wasn’t over. And Johnston was still the rebel admiral. He had one more big battle to fight.

It would happen in November, a few dozen kilometers east down the St. Lawrence. The Patriots were planning an attack on Prescott. They hoped to capture Fort Wellington. Pirate Bill would play an important role.

Things, yet again, got off to a rocky start. This time, quite literally. As the battle got underway early that morning and church bells rang the alarm on the Canadian shore, two of the ships that the rebels had stolen ran aground near the battlefield. Johnston was forced to come rescue them — and even he could only get one of them free. As a third Patriot ship tried to rescue the other stranded vessel, an American boat turned her cannons loose. The pilot of the Patriot ship had his head blown off by a cannonball; the new Patriot general, terrified, suddenly claimed he was sick, ordered the ship back to shore, and spent the rest of the battle hiding in his cabin.

Meanwhile, Pirate Bill had begun to ferry hundreds of soldiers across the river, taking them from the American side over to fight on the Canadian shore. Their first assault on Prescott fell short: the Canadian authorities, once again, knew the attack was coming. But by the end of that morning, the rebels had seized control of a big windmill outside town. (It’s still there nearly two hundred years later; it’s a lighthouse today and a National Historic Site.) The battle would become known as the Battle of the Windmill.

It lasted for days. The Loyalists attacked the windmill the very next morning, but it made for a pretty good fort. It had thick, stone walls and a commanding view of the St. Lawrence. Rebel snipers peered from the windows. It wouldn’t be easy to drive them out. More than a dozen Loyalists died in that first attack; dozens more were wounded. It seemed as if things had reached a stalemate.

But then, the Americans arrived.

Many ordinary American citizens supported the rebel cause. But the American government was a different story. The Patriots had long hoped that President Van Buren would come to their rescue — or that the bloody battles on the border would eventually spark another full-scale war between Britain and the United States, which might end in a new, democratic Canada. At the very least, the rebels hoped the American government would look the other way — allowing them to use the United States as a safe haven from which they could launch their attacks. The United States, after all, was still no fan of the British. It had only been a couple of decades since the War of 1812. And indeed, it didn’t seem as if the American authorities were in a rush to prosecute the rebels or their supporters.

But there was a limit. And the rebels had finally reached it. Van Buren wasn’t going to allow them to drag his entire nation into war. He was going to put a stop to it. He was going to close the border. And he was going to do it right in the middle of the battle.

As the fight between the Patriots and the Loyalists raged, suddenly there was a new arrival: the United States Navy. The Americans seized the big Patriot ships. And an American vessel took their place, patrolling the water in the middle of the St. Lawrence, cutting off the rebel supply line and making it nearly impossible for Pirate Bill to ferry any more soldiers across the watery border.

That night, the pirate admiral roamed the port on the American side, desperately trying to convince his troops to hazard the short journey across the river. Some agreed and he rowed them over himself, sneaking by the American patrol. He spent the next two days trying to convince more men to join the fight — and watching the battle at the windmill from across the river. He barely ate and he barely slept. He watched his dream crumble from the roofs of the American town. Now, the Royal Navy was moving in. Big guns were beginning to arrive. The rebels had run out of ammunition, reduced to firing door hinges and whatever other scraps of metal they could find. The end was drawing near.

On the final day of the battle, the Loyalists bombarded the windmill with artillery. The rebels were doomed. And with all their escape routes cut off, there was nowhere for them to go. Dozens would be killed or wounded. The rest, finally, surrendered.

The Patriot War was now pretty much over. The Pariotes rebels in Québec had finally been crushed just a few days earlier. There would be one more attack on Windsor, but that was crushed too. A year after William Lyon Mackenzie led his army down Yonge Street, the Canadian revolution was finally over. It had failed.

Many of the Patriots would be hanged. Some didn’t even get a trial. Nearly a dozen men from the Battle of the Windmill were executed. Dozens more would be sent into exile in Australia — some of those would die there from the poor treatment and harsh conditions of the prison camps.

But times were changing in Canada. The days of the Family Compact were numbered. With the most radical Canadian democrats dead or exiled, the moderates took over. Just ten years after the end of the Patriot War, they were able to win at the ballot box what Mackenzie and his rebels had been unable to win at the end of a rifle. The supporters of Toronto’s Robert Baldwin and Montreal’s Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine joined forces to bring Responsible Government to Canada. Democracy had finally arrived.

And with it came pardons for those who had fought in its name. The exiled Patriots were finally allowed to come home. Even the rebel mayor was officially forgiven. William Lyon Mackenzie returned to Toronto, where he would live out the rest of his days. He was even re-elected to parliament.

As for Pirate Bill Johnston, well, at the Battle of the Windmill he’d narrowly evaded capture yet again. But with the war over, he soon turned himself in to the American authorities so his son could collect the reward. He had always said there was no prison in the world that could hold him. And over the following months, he proved that to be true: over and over again, he would get caught or turn himself in, only to escape when the mood struck him. Eventually, they just stopped trying to find him at all.

Pirate Bill returned to his quiet life in the Thousand Islands. And once President Van Buren had been tossed out of office — thanks in no small part to his wildly unpopular intervention in the Battle of the Windmill — the American government even gave Johnston a plum post as the lightkeeper of the Rock Island Lighthouse. The man who would be remembered by history as a pirate, spent his later years watching over the treacherous waters he knew so well — making sure others could travel them safely.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more sources, images, links and related stories there.