Back in May and June of 2015, the Guardian newspaper ran an intriguing series on its Cities page entitled “A history of cities in 50 buildings.” The list is quite interesting: it includes several buildings no longer standing, such as the infamous Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in Saint Louis, Missouri, and the World Trade Center in New York, and some iconic, transformative landmarks such as the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and even the first Starbucks location in Pike Place Market, Seattle.

In Toronto, the Guardian chose Honest Ed’s as Toronto’s entry on the list. Of course, the Guardian’s list wasn’t meant to include the world’s most famous or iconic buildings, but chose an assortment of structures, standing, demolished — or in Honest Ed’s case, imperiled — meant to “tell unique stories of our urban history.”

[Disclosure: I contributed to the Guardian Cities site in February, 2015, discussing new streetcar systems in American cities.]

Over six months later, the Toronto Star finally noticed the Guardian’s inclusion of Honest Ed’s in the list of 50 buildings. The Star sought the opinion of two local architecture professors, Vincent Hui, of Ryerson University, and David Lieberman, of the University of Toronto. Hui agrees with Honest Ed’s inclusion, while Lieberman says that “at first glance, [the Guardian’s series] is a really dumb list.”

In some ways, Honest Ed’s — that kitschy emporium of bargains, bad puns, and faded memorabilia, fits the criteria of the Guardian’s list. The store was innovative (it was one of the first stores to feature “loss leaders” and store greeters), it served the needs of Toronto’s growing post-war immigrant communities, and was the starting point for a larger empire that included theatres in Toronto and London. The store’s replacement by a new mixed use development proposed by Westbank, is also part of Toronto’s story, as it becomes an increasingly high-rise city. So I agree with its inclusion in the Guardian’s list, based on the newspaper’s interesting (and provocative) criteria.

But if you were to ask me, I’d select two different buildings that would best represent Toronto’s modern history: the Toronto-Dominion Centre and City Hall.

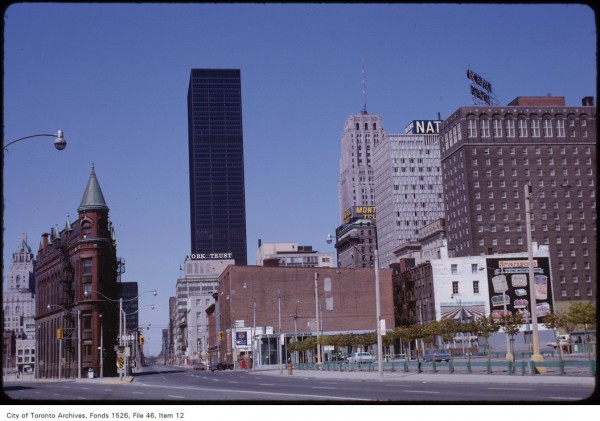

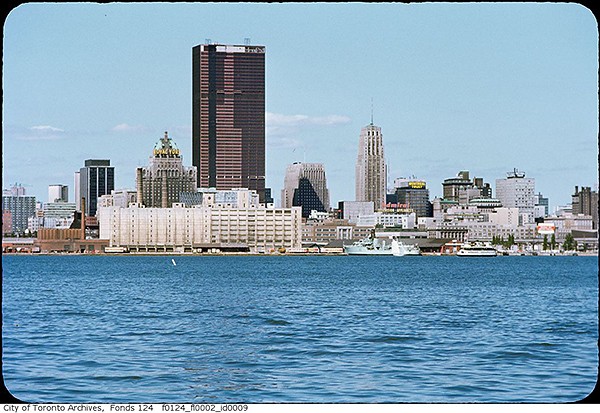

Construction began on Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s modernist Toronto-Dominion Centre in 1964; the first tower was completed in 1967, the year of Canada’s centennial. Unsatisfied with various proposals for the consolidation of the merged bank’s office space (the Bank of Toronto and the Dominion Bank joined in 1955), Phyllis Lambert, adviser on the architectural review for the T-D complex, helped to bring in the famous German-American architect to design something special.

Looking at archival photographs, it appears that first black tower fell on Toronto like the monolith in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. The old city of stone, brick, and wood, punctuated by a few office buildings and many church spires, was suddenly interrupted by a new age of steel and glass. It seemed that all of a sudden, Toronto was awoken from its slumber as a quiet, boring, Protestant provincial city, and began to emerge as an exciting cosmopolitan metropolis. Three additional buildings later joined Mies van der Rohe’s vision of two towers surrounding a banking hall, and other skyscrapers have surrounded the complex, but the Toronto-Dominion Centre remains an important and historic symbol of Toronto’s rise as an economic powerhouse and of a modern, global city.

A few years earlier, in 1955, Torontonians elected its first non-Protestant mayor, Nathan Phillips. Up until Phillip’s election, every mayor of Toronto elected in the twentieth century was a Protestant member of the Orange Order, a sectarian (and historically anti-Catholic) organization that dominated city politics and business. Phillips, on the other hand was Jewish, signalling a change in the city’s attitudes. Meanwhile, the federal government was finally loosening its restrictive immigration laws, setting the stage for the Toronto’s cultural transformation. Phillips championed a new City Hall, whose construction began in 1961, designed by Finnish architect Viljo Revell. Construction of the new city hall (and the square named for its champion, Mayor Phillips) was completed in 1965.

Toronto City Hall and Nathan Phillips Square serve as the focal point of the city. Fifty years later, the square remains popular; hosting ice skating in the winter, and concerts, festivals, commemorations, rallies and protests year-round. The Toronto Sign, introduced for the 2015 Pan-Am/Parapan Games, has been an especially popular addition to the square among residents and tourists alike. Like the T-D Centre, City Hall is a built reminder of an important turning point in Toronto’s history.

Honest Ed’s has an interesting history, and many Torontonians will be sad to see it close at the end of this year, even if they don’t shop there. I lived two blocks away, on Palmerston Boulevard, for two years, and while I barely shopped there myself, the store’s blinking lights and the historic Mirvish Village buildings were a welcome and even comforting local landmark.

But I’m optimistic that Westbank, the developers who were responsible for the Woodward’s project in Vancouver’s Downtown East Side, will be sympathetic to the site’s history. In Vancouver, part of the original store, long abandoned, was preserved. The iconic “W” sign was also saved, and there are many other nods to the local neighbourhood’s history. In Toronto, it appears, so far, that Westbank will construct a fitting new multi-use complex that will prove to be an asset to the neighbourhood.

Westbank’s Woodwards redevelopment preserved part of the historic department store, and includes condos, institutional space, retail, public spaces, as well as affordable and assisted housing.

One comment

Great photo of TD towers.