When the Imperial Oil company began assembling land for its new executive offices on St. Clair Ave. W. in 1952, it didn’t reckon on tangling with local homeowner Isabel Massie.

The widower, who was in her 70s, lived on Foxbar Rd. on a site earmarked for the surface parking lot at the rear of the 19-storey building.

Massie’s property poked deep into land required by Imperial Oil, and the multi-national energy company sent a team of men with briefcases to buy her property in May of that year.

Like her neighbours, Massie refused the first round of offers. “Thank you very much, but I like it here,” she told them. The men soon returned with bigger offers and one-by-one the homeowners sold up. Everyone, that is, except for the feisty senior.

“I know I’m a great inconvenience to you,” she recalled telling Imperial Oil in the Globe and Mail, “but I’ve always been happy on this street and I just want to stay here. It’s so nice and quiet.”

Massie’s grew up on Foxbar Rd. in another house owned by her parents. She told the papers she had always planned to stay on the street for life.

Imperial Oil offered as much as $100,000 for her house and property, but it didn’t work. “All they could offer her was money—and she wasn’t interested in it,” reported the Globe and Mail.

Isabel Massie’s stubborn refusal forced builders to move the footprint of the tower closer to St. Clair Ave. As the Modern-style structure rose from the ground, it dwarfed the startlingly isolated two-storey home.

Rather than find ways to spite Massie, Imperial Oil appeared to accept the situation with reluctant good will. The company built her a new fence, planted a hedge, and landscaped her yard. When a chunk of construction material punched a hole in the roof of the carriage house at the end of her yard, the structure was quickly repaired.

Aerial photos taken in the 1950s and 1960s show just how much the Massie house affected the Imperial Oil building. Her fenced-in yard backed right up against the tower and the employee parking lot abutted it on all both sides.

A decade after Isabel Massie’s victory over big oil, another holdout situation was brewing on St. Patrick St. near Queen and University.

In 1967, developer Windlass Holdings was aggressively acquiring land for what would become the Village by the Grange complex. The original proposal requested three 29-storey apartment buildings on the site east of McCaul St., south of Dundas St.

Slowly, the developer secured the rights to dozens of the small properties it needed in order to realize its high-density project, upsetting many locals in the process.

Abner Steinberg, who rented his former family home on St. Patrick St. just south of the development site, said Windlass’ policies were “an extreme example of blockbusting.” He told the Toronto Star in 1973 that he’d received more than 300 directives on his home and countless visits from building inspectors.

“One building inspector felt so bad about coming back to our house repeatedly,” Steinberg said. “He told my wife: ‘I’m under extreme pressure. I understand Windlass is trying to buy your house. Why don’t you sell it to them?'”

Kay Parsons, a member of the Grange Park Residents Association that opposed the development, echoed the sentiment. “I don’t want to move to the suburbs and I don’t want to move to the other side of Spadina,” she said. “Windlass is better able to move than I am.”

The owner of a mid-terrace house at no. 54 1/2 St. Patrick St. felt the same way. Despite the three other houses in the same row being bought and demolished for Village by the Grange, two hung on, refusing to sell.

After a protracted planning battle, the city under mayor David Crombie, the developer, and local residents came to a compromise: The three-tower concept would be replaced by townhomes and a group of mid-rise residential buildings, none of them exceeding 12-storeys.

20 percent of the properties were made available to the Ontario Housing Corporation as affordable housing and a retail outlets and a daycare were added to the blueprints.

Unfortunately, all this came too late for the row of Victorian homes on St. Patrick St. Portions of the terrace were awkwardly demolished, leaving two mid-terrace homes marooned—their carved-up exterior making their fate obvious to passers-by.

In the decades that followed, the remaining pieces of the terrace were also demolished, leaving 54 1/2 awkwardly marooned.

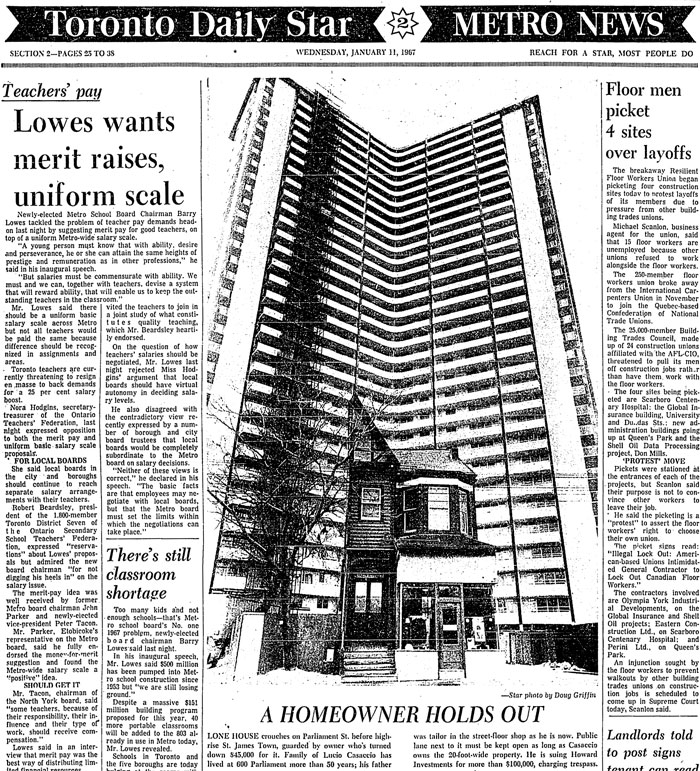

In 1965, two more holdouts threatened to disrupt the massive St. James Town development at Parliament and Bloor streets.

First there was tailor Lucio Casaccio at 600 Parliament St. He turned down multiple offers from developer Howard Investments for the little timber-framed home that had incubated him and the family business started by his father in 1915.

As his neighbour’s home gradually met the wreckers, Casaccio insisted Howard pay $100,000 for the right to clear his property. They refused, and he dug in deep, eventually becoming the only pre-1960s building on the west side of Parliament St. north of Wellesley St.

“It sticks out like a sore thumb,” said controller William Dennison, who called for a change in the laws governing expropriations. The future Mayor of Toronto wanted the city to have the right to purchase land and hand it over to developers—an idea the Star called “a dangerous doctrine” in a 1965 editorial.

At the time, land could only be expropriated for a genuine public purpose. Because St. James Town was a private development, the city couldn’t force Casaccio to sell, even though Howard owned all the other properties between Ontario, Parliament, Howard, and Wellesley streets.

“We have told him we are reaching the point where we are no longer interested in buying his property for anything more than its nuisance value, but he won’t believe it,” said Elmore Houser, lawyer for the developers.

In the end, the first phase of St. James Town was built around Casaccio. His house is still there in a heavily altered form as New World Coin Laundry.

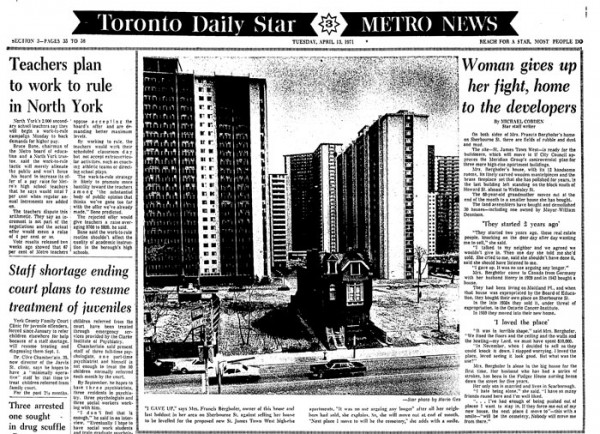

During construction of the second, western phase of the high-rise apartment complex, 68-year-old grandmother Francis Berghofer found herself in a similar situation.

Her 12-room Victorian home on the east side of Sherbourne St., just north of Earl St., was directly in the way of a planned building.

Together with a neighbour, Berghofer decided she wouldn’t sell. She’d had enough of moving. Her first home on Maitland Pl. was expropriated by the Board of Education, and her second, also on Sherbourne St., at one time looked likely to be claimed by the Ontario Cancer Institute, so Berghofer and her husband moved again to their presently threatened home.

“It was in terrible shape,” she told the Star. “We fixed the floors and the ceiling and the walls and the heating—my Lord, we must have spent $10,000.”

“I’ve had enough of being pushed out of places I want to stay in.”

Berghofer appeared prepared to fight on until her neighbour and ally suddenly sold. “She cried to me, said she shouldn’t have done it, said she should have listened to me,” she told the Star.

In November, 1970, her husband in a long-term care facility, Berghofer agreed to sell the home. Photos taken at the time show her beloved property marooned in a sea of rubble.

“It was no use arguing any longer,” she said. “Next place I move to will be the cemetery.”

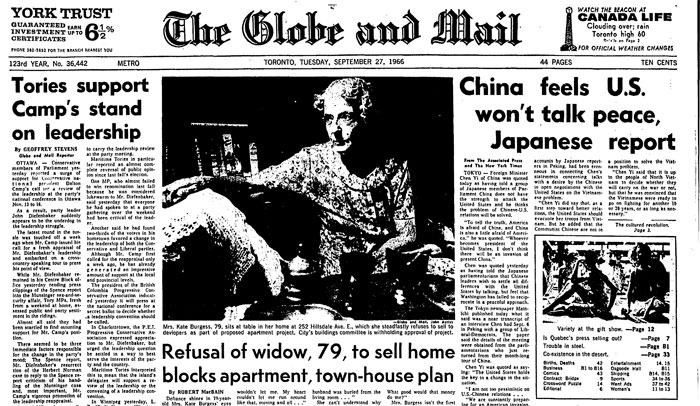

And then there was Kate Burgess, the indefatigable 79-year-old Hillsdale Ave. resident who attempted to block a high-rise residential development that called for the demolition of the home she built with her husband in 1910.

In 1966, Greenwin Construction Co. offered Burgess $40,000 and the opportunity to live rent-free in the house for the rest of her life if she agreed to part with the semi-detached property that was standing in the way of their 24-storey, 478-suite complex.

Unswayed by money or offers of alternative accommodation, Burgess fought back against Greenwin and many of her neighbours, many of whom had optioned their homes to the developer on the condition the project be able to proceed.

“I sandpapered every bit of woodwork there is,” she told the Globe and Mail. “I couldn’t let it go. Every brick they knocked down would be a drop of blood out of my heart and I’d have no blood left.”

“The only way they’ll get me out of this house is over my dead body and I hope the good Lord spares me for a few years yet.”

The Greenwin proposal would have razed much of the block bound by Hillsdale, Redpath, Soudan avenues, and Mt. Pleasant Rd. The 24-storey apartment tower would be the first of four phases of construction to be completed over several years.

Realizing Burgess wasn’t going to budge, the developer altered its plans, offering to incorporate her home in a row of townhouses. The city’s Buildings and Development Committee approved the revised idea by a vote of 9-1 in February, 1967, and council followed suit, voting in favour 15-5.

As a gesture of goodwill, Greenwin agreed to put $40,000 in a trust account for Burgess or her heirs should they decide to sell within 20 years.

Then, with the beginning of construction at hand, the Ontario Municipal Board blocked the city’s decision by refusing to alter the zoning on the site, killing the project.

Burgess died of a heart attack six days after the OMB handed down its decision.

“I’ve had sickness, sorrow, death and happiness in that house,” she told the Globe and Mail in June, 1967. “Do you think I’m going to turn those memories away for the greenbacks? Not me.”

Her house and all the others purchased by Greenwin are still standing.

Isabel Massie’s holdout battle with Imperial Oil ended with her death in 1964. Her children sold the property in 1965 and it was quickly and quietly cleared for an expansion of the rear parking lot.

After completion of the Imperial Oil tower, the exposed position of Massie’s home meant it was frequently jostled by strong winds, forcing the elderly occupant to burn more oil to keep warm in winter.

“No, she never at any time bought her furnace oil from us,” said an Imperial Oil spokesman when the purchase of the house was revealed in the Globe and Mail.

“She wanted to remain there for the rest of her life—and she did,” the paper reported.

One comment

You should also check out the Huron-Sussex neighbourhood. The University of Toronto used to go around in the late 1960s-1970s with briefcases of money and documents, trying to persuade homeowners to sell their properties. If owners declined, the University would threaten legal teams, expropriation, and other mishaps. It was pretty successful for the University, as they now own 84/100 properties in the neighbourhood.