In 1914, John Eaton, the third son of retail magnate Timothy Eaton, began preparing plans for a massive expansion of his family’s empire.

Aged 38, John had spent almost his entire working life in various positions inside the T. Eaton Company, many of them in senior management alongside his father.

When his father died in 1907, John inherited the company and took over as president. Under his leadership, the department store based at Queen and Yonge would—he hoped—go national.

The first T. Eaton store outside Ontario opened in Winnipeg in 1905, and John directed the company to begin secretly assembling land for a massive new Toronto flagship store at Yonge and Carlton streets in 1912.

Designed by renowned Chicago architect Daniel Burnham (he and his partner John Root designed much of the World’s Columbian Exposition,) the initial plans for the store were magnificent in scale: a 10-storey Beaux Arts structure with a curved frontage and massive skylit central atrium.

The company got as far as issuing the contracts for the structural steel when the First World War started in July, 1914. John Eaton ordered the project immediately halted as many of his workers joined the Canadian armed forces and steel became a vital resource in the war effort.

It wouldn’t be the only time Eaton’s College Street store would be a victim of unfortunate timing.

Two decades later, in 1929, another soon-to-be abortive construction project took shape on the eve of the Great Depression.

At 26-storeys, the Victory Building at 80 Richmond Street West was supposed to be the tallest all-concrete structure in the British Empire. The exterior, adorned with a multitude of artistic flourishes, was specifically designed by architects Baldwin and Greene with input from Toronto high-rise specialist Henry Falk to emphasize height and stature.

New York sculptor A. J. Goodelman was brought to the city to carve and install an elaborate Indiana limestone sidewalk canopy, while on the roof, a massive concrete ziggurat was anticipated to crown the building.

“A tall office building is a sort of mountain, a civilized city mountain,” architect Falk told the Toronto Daily Star in September, 1929. “What impresses us in a mountain, whether in nature or the city, is its mass and contour, not the details on its surface.”

The Victory Building sprang from the ground at a tremendous pace. In just five months, the builders had completed the shell of the 15th floor and were continuing skyward. However, market forces in Toronto and the rest of the world were beginning to cloud the building’s outlook.

The October, 1929 stock market crash halted work on the project at the 21st floor and rumours began to circulate about its structural and economic viability. “Nothing short of an earthquake, so severe as to destroy the whole city, could shake the foundations of the Victory Building,” Falk reassured.

The work stoppage, he said, was merely due to the rapid pace of construction. The funds for the final stage of the project were unavailable because of the record-setting pace of the build, he said. “A very bright future can be predicted for the Victory Building,” he added.

Unfortunately, as the Depression began to bite in early 1930, all work halted and the tower became a conspicuous shell. Despite numerous plans to fund the final eight floors and roof, the Victory Building stayed a stump for seven years, devoid of much of its promised architectural glory.

A new buyer finally bought the dormant structure in 1936, adding a few utilitarian additional floors and squaring off the roof. Tenants moved in on April 1, 1937, but the Victory Building never did quite fulfil its architects’ grand ambitions.

Perhaps Toronto’s most famous unfinished structure loomed like a spectre over the Don Valley for more than 20 years.

The Hampton Park Apartments, better known as the Bayview Ghost, started life in 1959 as a controversial 800-unit residential complex. When finished, the development would have looked over the Don Valley from a perch northeast of Rosedale, above Bayview Avenue, and included a swimming pool and putting green.

There was trouble almost from the moment East York approved Hampton Park. The local council claimed it had acted in error and residents of the tony Governor’s Bridge neighbourhood fretted over the introduction of apartments, notes author Mark Osbaldeston in Unbuilt Toronto.

Despite the local acrimony, Hampton Park pushed ahead with construction, putting up the shell of the first 105-suite building in 1960. In a last-ditch effort to keep the project advancing, East York rezoned the land for single-family housing, a move that triggered more than two-decades of legal purgatory.

By the late 1970s, the property surrounding the crisp white shell of the Ghost still remained undeveloped. The bare land and elevated location in clear sight of the Don Valley Parkway fuelled the building’s legend.

Finally, in 1979, a new proposal for the site pitched by new developers inadvertently broke the stalemate. Instead of rezoning the land to permit construction of two 12-storey apartment blocks as asked, East York instead issued a demolition permit for the Ghost and acquired provincial legislation upholding its single-family housing bylaw.

In October, 1981, a wrecking ball painted like a jack-o’-lantern crashed through the walls of the Bayview Ghost, ending the saga once and for all.

“This shouldn’t have been demolished,” said Morris Freedman, a partner with Hampton Park Developments Ltd. “People should have been living here 22 years ago. But it’s a democracy. People get what they want.”

Today, the Bayview Ghost site is covered by two streets of single-family dwellings.

In more recent times, the concrete stump of the original Bay-Adelaide Centre provided stark warning that not all high-rise projects manage to make it off the ground.

In 1988, Toronto City Council gave the go-ahead to a controversial twin office tower project proposed by Markborough Properties (the real estate arm of the Hudson’s Bay Company) and developer Trizec Properties.

Essentially, council allowed Markborough to merge density from three separate properties into just one at the northwest corner of Yonge and Adelaide. In exchange, the developers agreed to provide space for a new affordable housing and a public park.

Toronto Star writer David Lewis Stein called the Bay-Adelaide deal “everything that is wrong with … city council.” A subsequent independent review, however, found the agreement to be satisfactory.

With the deal sealed, architecture critics praised the design of the skyscraper. The Star‘s Christopher Hume predicted the towers would become “instant landmarks.”

In 1989, builders excavated and built the Bay-Adelaide Centre’s six-storey underground parking garage on the south side of Temperance St., just east of Bay St. The central elevator core that would have formed the spine of the building rose six storeys above ground—and then the project fell apart.

The problem was the Bay-Adelaide Centre was promising to deliver a considerable amount of new office space at a time when surrounding towers were already partially vacant. Just five years earlier, the Toronto office vacancy rate was 13 percent, and in the meantime Scotia Plaza and BCE Place had arrived in the downtown core.

Unable to secure an anchor tenant for the Bay-Adelaide Centre, Markborough Properties put the project on hold in 1991. In 1993, it nixed the whole thing. “When word came … the Bay-Adelaide Centre had been killed, it came as a surprise to many that it had still been alive,” wrote the Star‘s Christopher Hume.

An attempt in 1998 to revive the project and build off the stump also failed because of a lack of tenants.

The partially-complete elevator core was finally razed in 2006 when Mayor David Miller and Brookfield Properties’ Ric Clark took ceremonial first swings at the concrete monolith.

With the First World War a decade in the past, the T. Eaton Co. was once again ready to further its ambition of building a flagship Eaton store at Yonge and Carlton, minus the man who masterminded the project.

John Eaton died of pneumonia in 1922 aged just 45 and the company was helmed by his cousin, Robert Young Eaton.

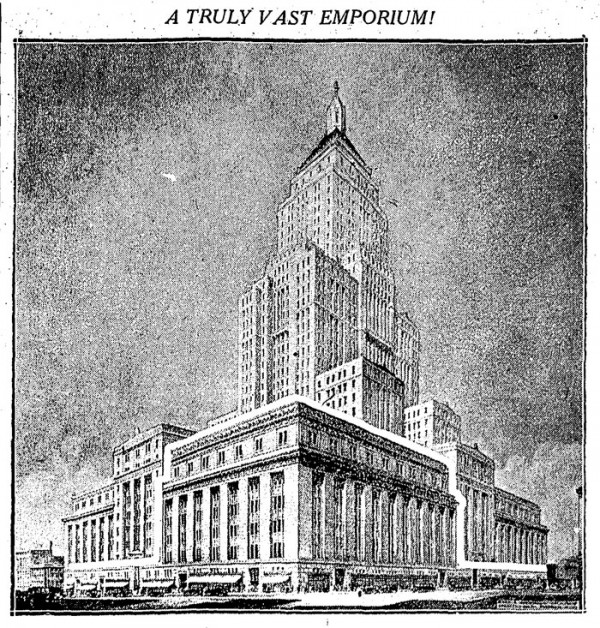

In November, 1928 his T. Eaton Co. revealed its plans for a retail emporium astonishing in scale and proportion. Instead of building the five-storey, Beaux-Arts store it had announced just a few months earlier, Eaton unveiled a colossal structure that would consume two city blocks between Yonge, Bay, Gerrard, and College streets—not Carlton, as the company had originally imagined.

Inside would be more than 2 million square feet of retail space spread over nine floors. All of Eaton’s administrative offices would be relocated to the building and there would be space for a theatre, dining hall, and a grand arcade connecting Bay and Yonge streets.

A 670-foot tower, more than twice the height of the clock tower of Old City Hall, would crown the whole thing. It was to be Toronto’s Rockerfeller Center—the biggest retail development in Canada to date.

Construction began as planned in 1928, but the Great Depression quickly scuppered progress, and only the first phase of the building at the southwest corner of Yonge and College materialized. Though only a fraction of the building was built, the deep foundation pilings for the central tower lingered in the ground until the 1980s.

Today, the widened sections of Yonge and College/Carlton in the area hint the great store that was lost in the financial crisis.

Interestingly, land on Carlton Street the T. Eaton Co. sold when it switched its sights to College Street gave rise to another abortive high-rise project in the form of the Toronto Hydro Tower. As it was originally planned, the structure that presently stands just east of Yonge was meant to support an 20-storey skyscraper.

It would take until 1977 for Eaton’s to get its modern Toronto flagship in the Eaton Centre.