The City of Brampton — Canada’s ninth largest municipality — was founded as a small community in the mid-19th century, as the interior of Southern Ontario was opened up to settlement by immigrants from the British Isles and the United States.

Buffy’s Corners, as Brampton was originally known, was where Hurontario Street, an important settlement road met the 5th Sideroad of Chinguacousy Township and a little stream known as the Etobicoke Creek (once sometimes known as the Etobicoke River). The creek wasn’t powerful enough for mills to establish themselves along its banks, but it was still useful for local commercial uses. Many of Peel’s early settlers arrived from Cumberland, England; the village of Brampton, incorporated in 1853, took its name from a small market town near Carlisle.

The arrival of the Grand Trunk Railway in 1856, the Credit Valley Railway in 1879, and the village’s status as the county seat for the newly established County of Peel saw Brampton grow into a regional centre and became a town in 1873. The town became famous for its many greenhouses, and Brampton became known as “The Flower Town of Canada.” New commercial buildings befitting a booming county town were built in the Etobicoke Creek’s floodplain, even on top of the little waterway. By the 1940s, Brampton was a bustling town with a population of about 6,000 and had a diversified economy, but was not yet part of Toronto’s commuter shed.

Main Street North, March 1948. Russell Cooper fonds, Region of Peel Archives/PAMA

Unfortunately, by building its town centre around and on top on Etobicoke Creek, Downtown Brampton would annually flood during the spring snow melt and sometimes after major storms. Notable floods occurred at least once a decade — storms even claimed a lives in 1911, 1918, and 1943.

But a severe flood in March, 1948, pictured above, finally resulted in action. That year, up to six feet (1.8 metres) of water covered Main and Queen and caused nearly $500,000 in damage ($5.6 million in 2016 dollars), but no fatalities.

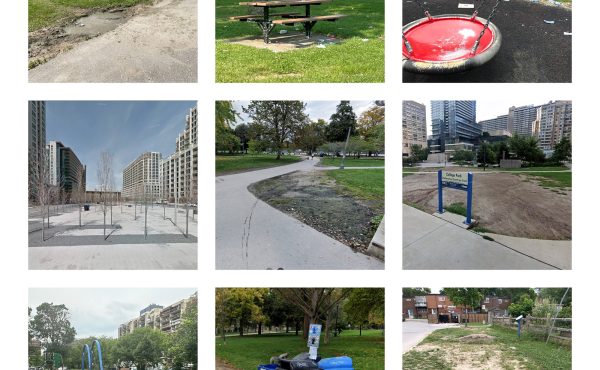

Between 1950 and 1952, the Etobicoke Diversion Channel was built to the east, around the Downtown core, between Church and Wellington Streets. The diversion saved Downtown Brampton from future flooding — particularly Hurricane Hazel in 1954 — but it ended up sealing the creek off from the downtown core and even some of the parks that line the creek. Several houses were demolished, and streets were either re-routed or closed off. The diversion channel is completely fenced off, and “no trespassing” signs are found throughout.

Some ghosts of Etobicoke Creek’s old route remain throughout Downtown Brampton. A retaining wall on Main Street south of Wellington is the most visible remnant, but the topology betrays the location of the old creek. Queen Street leads uphill in both directions from the historic Four Corners at Main Street, and St. Mary’s Catholic Church, built in the early 1960s, is located in a lush lowland that was once part of Etobicoke Creek’s path.

Retaining wall on the east side of Main Street South. The creek ran between the street and the houses in the background.

Earlier this month, I led a Jane’s Walk through Downtown Brampton, discussing the town’s soggy history and highlighting the challenges the concrete channel creates as well as long-term plans to reintegrate the diversion into the public realm and further improve flood protection for Brampton’s downtown core. One of the best parts of a good Jane’s Walk is when local residents participate and share their knowledge; one of the things that I learned is that fish, including freshwater salmon, are returning to Etobicoke Creek, but fish can not navigate through the diversion channel, especially where the water drops through a sluice near the railway corridor. At the very least, a fish ladder is required here.

On the Etobicoke Creek Jane’s Walk on May 7, 2016

South of the diversion channel, Etobicoke Creek is located in a lovely ravine; a multi-use path extends south to Steeles Avenue and is completely separated from auto traffic. North of Church Street, a path continues all the way past Brampton’s city limits and into Valleywood, a residential subdivision in the Town of Caledon. The diversion channel is a gap in between; trail users must ascend to city streets to continue along the route.

In preparing for the walk, I spotted a great blue heron; I was later told during the walk that it wasn’t an uncommon sighting. This is a great ravine — one of many great sections of “Accidental Parkland” that wind through the Greater Toronto Area.

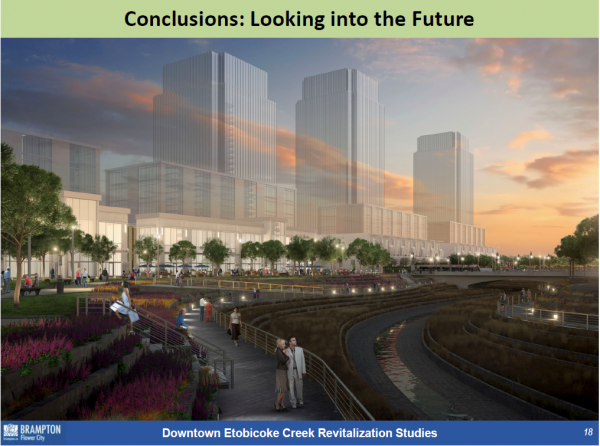

Happily, The City of Brampton is currently proposing major changes to the diversion channel revitalize Etobicoke Creek through Downtown Brampton. It would create new public spaces while further mitigating any potential flooding in Downtown Brampton, which remains a floodplain. Improving the flood control measure will encourage new development in the east side of the Downtown Core.

Renderings show new public paths, terraced gardens and green spaces, with cafes, restaurants and other businesses alongside the creek. Conceptual mid-rise and high-rise developments are shown, part of a larger plan to rejuvenate and intensify Downtown Brampton. The concrete channel will require major repairs in any case; the proposed improvements to the public realm and flood control measures are an exciting project.

Conceptual drawing of revitalized Etobicoke Creek

Unfortunately, last year Brampton City Council declined to build a fully-funded light rail transit (LRT) line up Main Street to Downtown Brampton; for now, the Hurontario LRT will terminate at Steeles Avenue. Some community groups — such as One Brampton — are advocating for the rejected Main Street route, while some city councillors and local citizens are pushing for an alternative alignment through the Etobicoke Creek ravine. City staff and transit consultants looked at this option and rejected it due to difficulty of construction through a floodway, incompatibility with existing official plans, and its indirect routing. As the City of Brampton is both looking at revitalizing a great local resource, building a transit corridor through the Etobicoke Creek ravine probably isn’t such a great idea.

Despite the LRT controversy, there is plenty of opportunity for Downtown Brampton, an often overlooked urban centre with a wealth of heritage buildings and some nice public spaces such as Gage Park and Garden Square. It’s encouraging to see local support for improving Etobicoke Creek through Downtown Brampton and to meet engaged residents to discuss the future of this historic urban centre.

Etobicoke Creek looking north to the start of the diversion channel, just south of the Canadian National Railway tracks