Charlie Pachter is a butter tart fan. Actually, calling him a fan is probably understating it. He loves the things.

Pachter, who once met Queen Elizabeth II after painting her on a moose (a piece that the Queen called “amusing”), once traded a painting to Wilkies Bakery in Orillia for a lifetime supply of the distinctly Canadian snack. “I’m addicted to butter tarts,” he says. He continues, describing the perfect butter tart: “Crunchy on the outside, runny in the middle, with raisins.” His addiction is equal parts gustatory and whimsically nationalist — Pachter has adopted butter tarts as an artistic motif not only because he likes them, but for their Canadian connotations (“Canadian iconography,” he calls them). So when the Baycrest Foundation couriered a large, plaster brain to Pachter’s doorstep, he followed his gut. And as such, his sculpture titled “Butter Tarts on the Brain” was born, and will soon be on display as part of a vast public art project being unveiled this week, called the Brain Project.

The Brain Project is a new city-wide public art project that calls to mind another famous public art project: the polarizing Moose in the City project, completed in 2000. This time around, though, it’ll be a far cry from the imposing moose of Y2K. Brains — over one hundred of them! — will be on display in various locations throughout Toronto this summer, each designed by different artists, community members, celebrities, and athletes.

The Brain Project is supporting Baycrest Health Sciences, a medical centre focused on research into Alzheimer’s, dementia, and other diseases that affect the brain as it ages. Co-founder Erica Godfrey (the daughter-in-law of Postmedia’s Paul Godfrey) was inspired to give back after watching her husband and co-founder Noah Godfrey’s grandmother living with dementia at Baycrest. “This is my crazy idea,” she says. “We have such a great culture here, and tons of talented people — why don’t we do something interesting for the public?”

The brains are both visually striking — who could miss Pachter’s brain (literally, a cluster of butter tarts on top of a big blue brain) in the street? — and a clear symbol for the cause of brain health. “It was really important for us to connect the shape of the sculpture to the cause,” says Godfrey. That there is a charitable cause underwriting the entire campaign is a major distinction — and, arguably, an improvement — upon the Moose in the City campaign (whose main beneficiary, financially, may have been the Benjamin Moore paint company, since artists were given coupons to buy paint and supplies). The overarching artistic conceit to the project is simple: all brains are different, and all brains are beautiful. And its message has an almost universal outlook — “100% of people have an aging brain,” notes Godfrey. “Almost everyone you speak to knows someone who has been affected [by aging brain disease].”

Populism aside, the Brain Project has garnered significant attention and involvement from A-list celebrities — which the organizers hope will help generate more fundraising dollars (the project’s expressed goal is to raise $1.5 million). Celebrities like Michael Bublé, Sarah Rafferty (Donna from Suits), and North West (yes, the daughter of Kim and Kanye) are all involved, either contributing a brain or, in the case of Rafferty, serving as the project’s Global Ambassador. Rafferty, a friend of Godfrey’s and part-time resident of Toronto, where Suits is filmed, was quick to jump on board with the project. “It’s a topic near and dear to me,” says Rafferty, whose grandmother had Alzheimer’s. “When [Erica] mentioned it to me, I said I wanted to do anything I can to help.” (She is also close friends with Mr. Brainwash, one of the higher-profile, Los Angeles-based artists contributing to the project.) In fact, the entire project has high-society Toronto connections: the founders of the project include Ben Mulroney, etalk host and son of former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, and Noah Godfrey, son of Postmedia’s Paul Godfrey. (In the interest of disclosure, Spacing is a media sponsor for the project.) It’s attracted large names in the art world as well — including the confusing character of Mr. Brainwash, the star of the Bansky-directed Exit Through the Gift Shop, who some have suspected is at the centre of a complex hoax orchestrated by Banksy, the infamous British street artist. (This has never been proven nor disproven.)

The Brain Project has big, moose-shaped public art shoes to fill, shoes that have not always been especially popular in Toronto. The project’s founders hope that the collection of brains will inspire people to seek them out, imagining a scavenger hunt-esque response to the brains that will increase awareness around Alzheimer’s and dementia. The project’s organizers and artists behind the brains that toe the fine line that public art projects — especially those with larger goals of conversation and awareness — must be weary of: they need to make their point, but not so much that they become (like the moose) something of an imposition on public space.

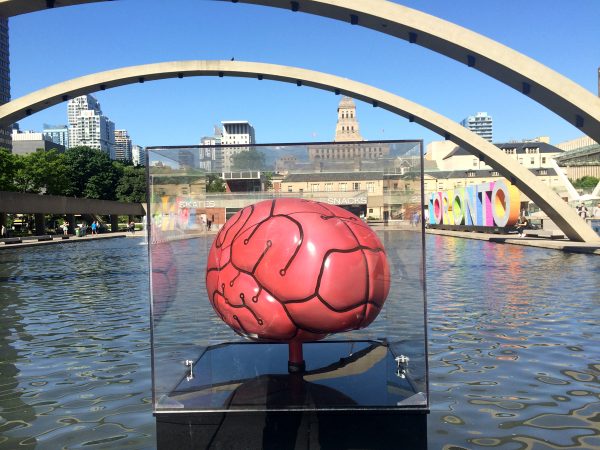

To do so requires a certain level of co-operation between the city and the project’s organizers. The City of Toronto, for their part, have been fully supportive of the Brain Project, and have helped coordinate the locations of the brains. As a result, the Brain Project will see art installations placed in high-profile locations — there will be a brain, for example, in the pond in front of the Toronto sign in Nathan Phillips Square. The only other art project to be installed in the pool was Ai Wei Wei’s 2013 Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads: Bronze. In addition to high-traffic locations like Nathan Phillips Square or Union Station, there will be brains on display at unique locations — including Billy Bishop Airport, and the Evergreen Brick Works “I wanted locations that had high traffic,” says Godfrey, “but also that have a mix of different types of people.”

Larger public art projects, like the Brain Project, can be difficult to pull off from an administrative standpoint. Since some of the more prominent brains (like the one slated to be installed in Nathan Phillips Square) will be displayed on city property, the city became heavily involved — and supportive — of the plan.”Often times at the city, ideas can be a little bit challenging to express,” says Jordana Novak, director of events at the Baycrest Foundation. “But we’ve had a group of people who are very interested in helping.” Specifically, the team at Baycrest has singled out the help of Coun. Josh Cole for his role in the project. “Without Josh’s guidance, we wouldn’t have been able to get as far as we did, as quickly as we did,” says Novak. The Brain Project is unique, and as such took some bureaucratic gymnastics to move forward. When it came to getting permits for city parks, the City “made kind of a custom arrangement,” says Novak, whereby the fees were waived. “For us, it was just about clearly and transparently relaying our vision that didn’t necessarily fit in a checkbox.”

The organizers hope, ultimately, that the Brain Project will be both an effective communicator of the message of awareness, and an effective fundraiser. The brains themselves are praised by those involved — Rafferty was particularly struck by the brain designed by Mr. Brainwash, which depicts tiny painters scrubbing the memories off a brightly coloured brain. “At the same that they’re beautiful and amazing, and full of hope for the future,” says Rafferty, “they’re also really sad. It’s both whimsical and funny, and heart breaking.”

For art fans, the project will offer plenty to appreciate, with over 100 different interpretations of the human brain. The brains will be on display in Toronto throughout the summer, after which they will be collected into one display (and then auctioned off) at Yorkdale Mall in October. In the meantime, however, brains will start to appear throughout the city this week.

For Pachter, who says he gets eighty to one hundred requests for charity art every year (partly, he says, because word must’ve gotten out that he’s an “easy hit”), getting involved with the Brain Project was a no-brainer. “This one pushed some buttons for me. […] Baycrest is a terrific organization,” he says. “They’ve been looking after people in their twilight years for so long.”

top photo by Matthew Blackett