A little over 30 years ago this winter, one of Toronto’s earliest Modern buildings was pulled to the ground. When the Shell Oil Tower at Exhibition Place was completed in 1955, Toronto didn’t have any steel-and-glass downtown office towers.

The most-prominent building in the city was Commerce Court, a 24-year-old limestone-clad bank building decorated with sculpted heads representing courage, observation, foresight, and enterprise. Its reign as the Commonwealth’s tallest structure prolonged by the Great Depression and the Second World War.

The Shell tower was conceived as an advertisement for Dutch petroleum giant, Shell Oil. The company invited four architects to submit designs for an “cheerful” observation tower, but didn’t stipulate the materials, decoration, or motifs.

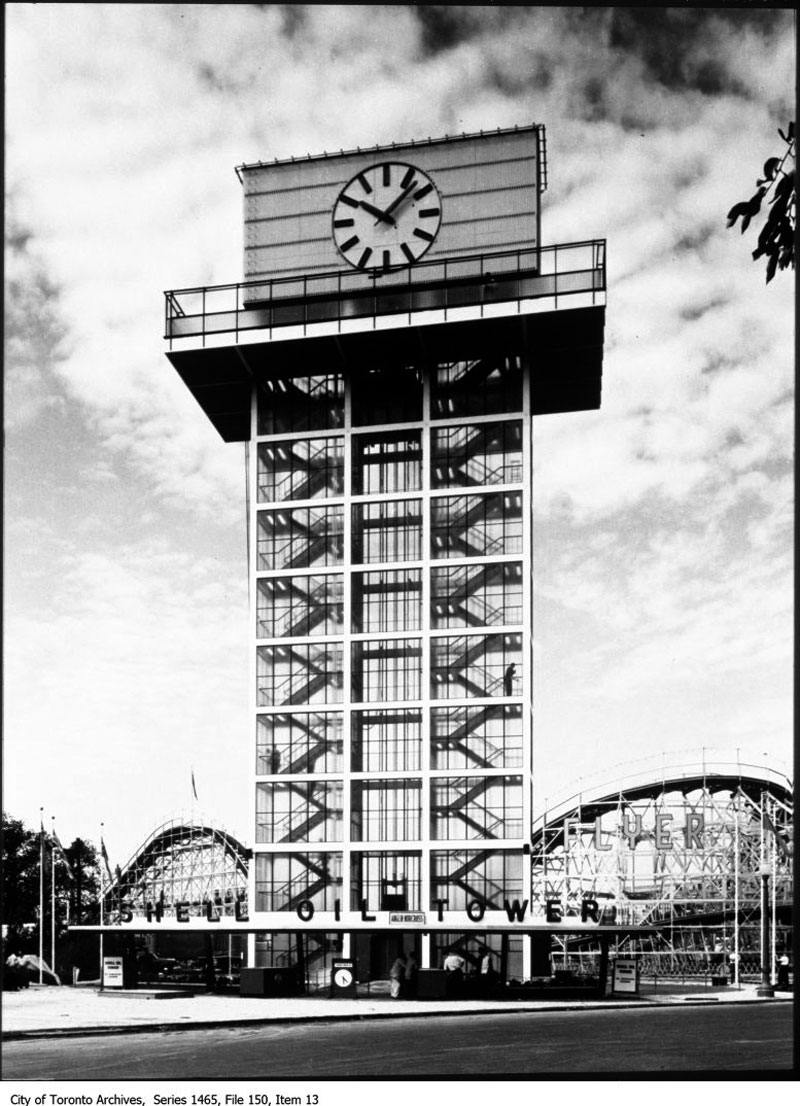

The blueprint submitted by architect and associate University of Toronto professor George Robb envisioned a rectangular, nine-storey column of steel and glass topped by a viewing platform and large analogue clock. A staircase spiralled up the outside and another descended within. Robb’s design was luminous and completely transparent thanks to its walls of glass.

“Exhibition architecture poses the architect a number of special problems,” wrote Canadian Architect magazine in its first issue in November 1955. “His building has to be gay, even flamboyant; it also has to withstand the concentrated assaults of crowds for short periods, and then be shut up for months on end.”

Shell Canada president W. M. V. Ash agreed to fund construction and maintenance of the tower as well as a $10,000 annual rental to the CNE. Advertising was to be strictly limited to the name of the tower and to the ground floor and admission kept free.

Though Robb’s design was modified (the exterior stairs were removed, most likely for safety reasons,) the model of the Shell Oil tower built starting in June 1955 was almost identical to the architects original vision.

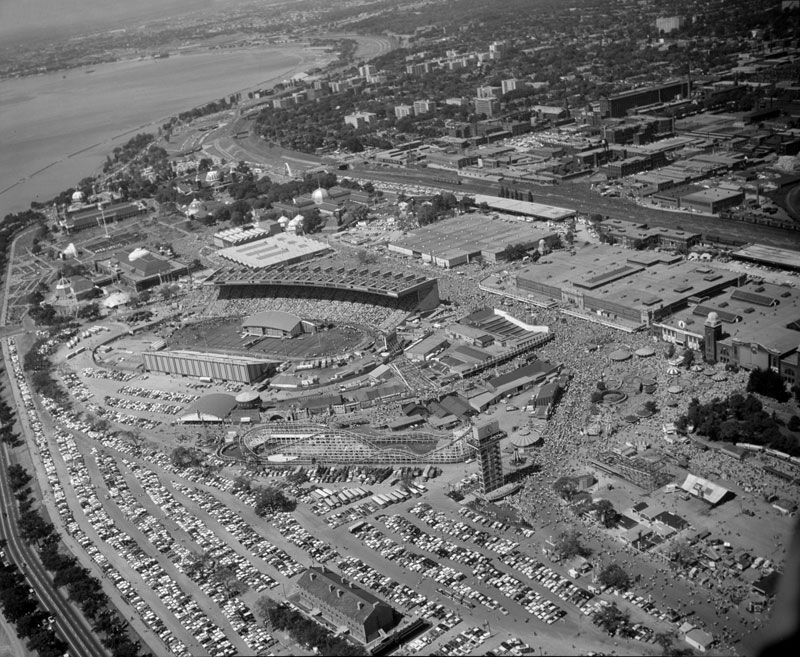

The 37-metre tower—the first in Toronto to have a skeleton made entirely of welded steel beams—was located on Princes’ Boulevard about 365 metres west of the Princes’ Gates. The clock at the top was 5 metres tall with one-metre numerals facing east and west and the whole thing painted in Shell’s red and yellow colour scheme.

On the hour, electronic chimes pealed out the hour over a public address system.

The Shell Oil Tower opened to the public at the start of the Ex on August 24, 1955. In celebration, the oil company released 50 gas-filled balloons containing coupons redeemable for $10 or $25 in cash.

“When the balloons burst paper bags will drift down. The bags have been painted with fluorescent red paint so they can be easily spotted,” the Globe and Mail reported.

That night, the glass tower and clock were illuminated for the first time with fluorescent exterior lights and incandescent internal bulbs. “Make it a meeting place—get into the habit of saying to your friends “Meet me at the Shell Oil Tower,” an advertisement in the Star that summer advised.

“An elevator is waiting to whisk you to the observation platform, far above the ground, where you can look down on the breathtaking spectacle of the greatest show on earth, the Canadian National Exhibition,” the advertisement read.

The Shell Oil Tower predated TD Centre and Commerce Court West, the first Modern skyscrapers in Toronto, by almost a decade and it was undoubtedly one of the most futuristic buildings in Toronto when it opened.

Its styling and structure foreshadowed many of the popular design styles of the decade to come: glass curtain walls, steel frames, bright lighting, and crisp angles. Yet despite its importance to the history of Toronto’s architecture, the tower was never widely prized or valued.

When Shell decided not to renew its lease, American watch company Bulova took over sponsorship in 1973, replacing the analogue clock with a clunky digital display that also showed the temperature.

The first threat to the tower’s existence came when the Blue Jays were planning a new stadium at Exhibition Place in 1983. The footprint of the proposed stadium overlaid on a map of Exhibition Place placed the pitcher’s mound directly on the site of the Bulova Tower.

At almost 30 years old, the steel and glass tower was in urgent need of maintenance. The stairs and elevators were structurally unsafe and required about $500,000 to fix, according to the general manager of the CNE, Winfield Stockwell.

“The tower won’t be repaired because it probably will be demolished as part of the [stadium] redevelopment,” reported the Globe and Mail.

Ultimately, the Blue Jays found a new home downtown, but the Bulova Tower was still in trouble. It remained closed to the public during 1984 and was once again in the crosshairs for demolition in 1985.

The proposed 2.87-kilometre route of what is now the Honda Indy Toronto ran directly past the tower and the board of Exhibition Place planned to knock it down to make room for a temporary pit lane complex.

Molson’s Brewery, the lead sponsor of the Indy, signed an agreement with Exhibition Place that allocated $150,000 for the demolition. Changing those plans would be legally challenging, lawyers claimed.

“Relocating the pit would remove it from the infield and affect the ability to market the area for catering and seating,” reported the Globe and Mail.

Despite its prominence, the Bulova Tower lacked any legal protections. The Toronto Historical Board, the now-defunct city agency responsible for protecting historic buildings, recommended the tower be shielded from demolition, but later reversed its decision after THB managing director Scott James met with CNE officials in late 1985.

“We had $150,000 in our budget to repair it, but the price has come in at close to $500,000,” said Exhibition Place general manager Bill Stockwell. “We would rather put money into older structures like the Music Building.

A “Save The Tower Action Committee” lead by architect Brigitte Shim and supported by Jane Jacobs and Pierre Burton held a last-ditch rally to save the tower in November. About 100 people gathered at Exhibition Place to release colourful helium balloons and collect signatures for a petition.

A plane flew over the city core with a sign reading: “Save the Bulova Tower.”

“We are quite outraged by the whole thing,” Shim told the Globe and Mail. “The tower occupies a special place in the memory of the CNE and nothing has been made public about the demolition.”

Ultimately, the rescue plan failed. Molson, in an effort to save face, conceded the tower could stay but the Toronto Historical Board’s decision not to protect the building meant there was nothing to stop the wreckers moving in at the end of November 1985.

“Protecting our heritage of the fifties means more than just replaying old rock and roll,” wrote former Toronto mayor John Sewell in his Globe and Mail column. “Not only is our distant past in our way, so is our youth. In this inflationary age there are some content only to live in the future.”

Architecture and design critic Adele Freedman blasted the THB for lacking the “guts and foresight” to save the tower.

THB managing director Scott James appeared to regret the board’s role in allowing the demolition of the tower in an interview a year later in 1986.

“The Bulova Tower is a loss I would regret,” he said. “The board has overlooked recent buildings for one reason or another … what we want to do is develop some criteria for assessing modern buildings.”

“In our sensibility, we’re up to Art Deco now,” he said. “It’s a slow process to turn around a ship.”

4 comments

The penny-pinchers (AKA fiscal conservatives) at their worst.

Another example of how Toronto does not know when it has a winner and what to do with it. Recently the TORONTO sign at City Hall has been a fantastic success yet, they keep wanting to mess with it.

The board of directors for the CNE have put profits over history. The CNE should be a show case of architecture over the years. Instead they tear down building for parking lots and give them to private business who have no interest in caring and preserving the buildings

Slowly our mid-century building are getting recognized. Unfortunately getting them listed is low, very low priority. When Yonge street got its designation 2 Carlton was left out.

Hindsight is always 20-20. Let’s pretend we can learn from history, and work toward saving another mid-century Toronto icon: the McLaughlin Planetarium building, threatened with imminent destruction.

Please contact your city councillor, your local MPP, please write letters to the editor, and most importantly, please contact U of T central administration to voice your support for the preservation of this irreplaceable component of our cultural heritage!

https://www.facebook.com/SaveThePlanetarium/