When Toronto’s first subway line opened in 1954, much of track north of Bloor Street was located in a shallow, open trench.

The money-saving open cut construction technique was an old one: The Metropolitan Railway, which became the Metropolitan line of the London Underground, used the same method to cut through the centre of London in the 1860s.

While it saved money versus conventional tunnelling, the result for Toronto was a large scar on the east side of Yonge Street from Church Street to Eglinton Avenue.

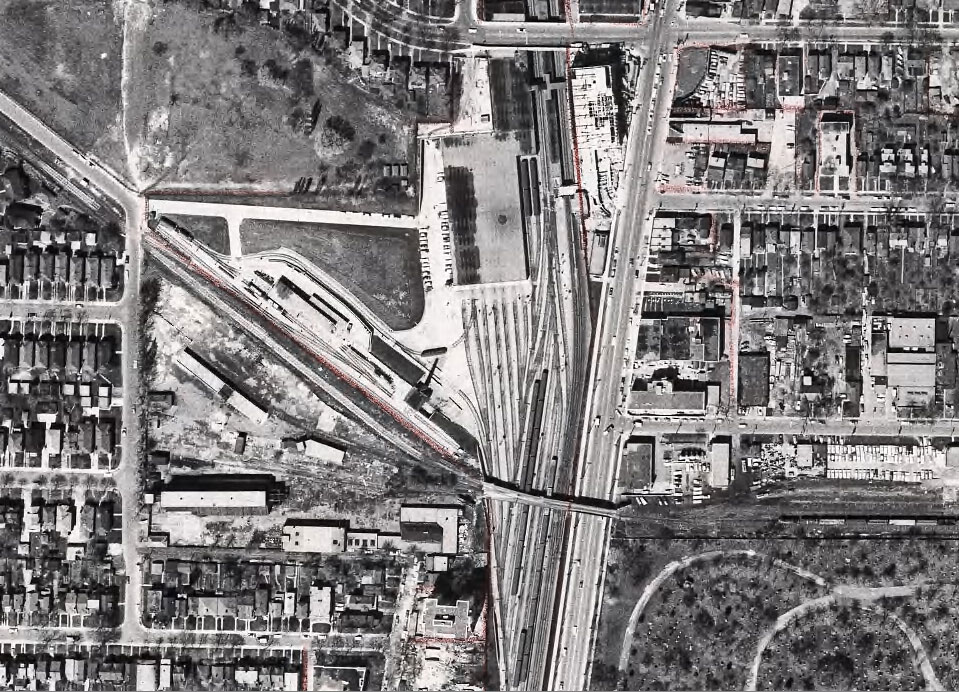

The most conspicuous outdoor area was in the Yonge and Davisville area, where the TTC built its service yard and train storage area. There, a tangle of tracks radiated out from the subway line, covering an area of approximately 10 acres.

Starting in the 1960s, the TTC began covering up some of the trenches due to safety concerns and noise complaints from neighbours. Between St. Clair and Summerhill stations, the line was hidden beneath a grass-covered deck (look out the window of the train and you can still see the sloped sides of the original cutting.)

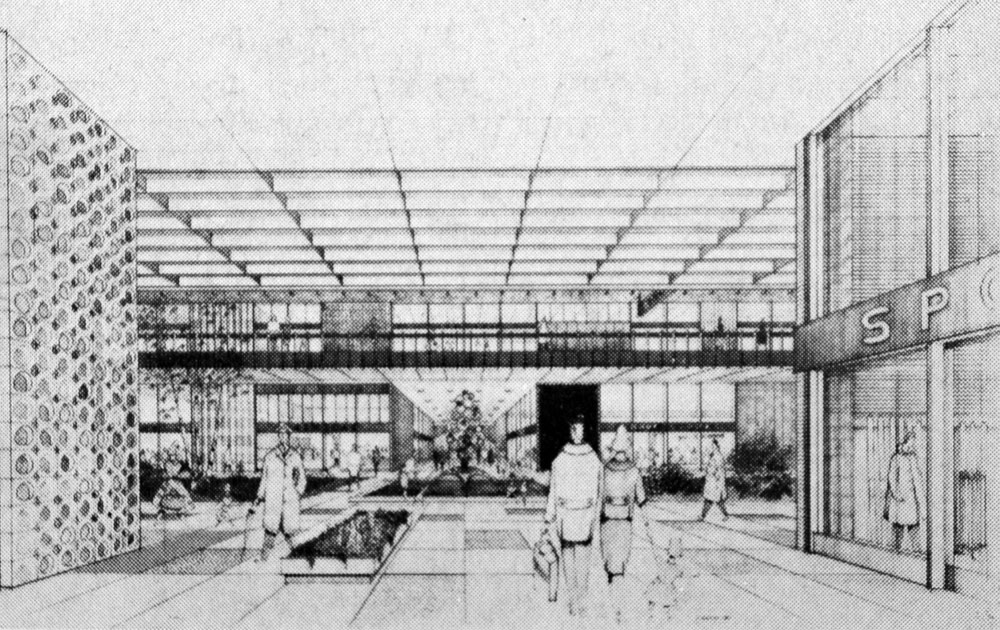

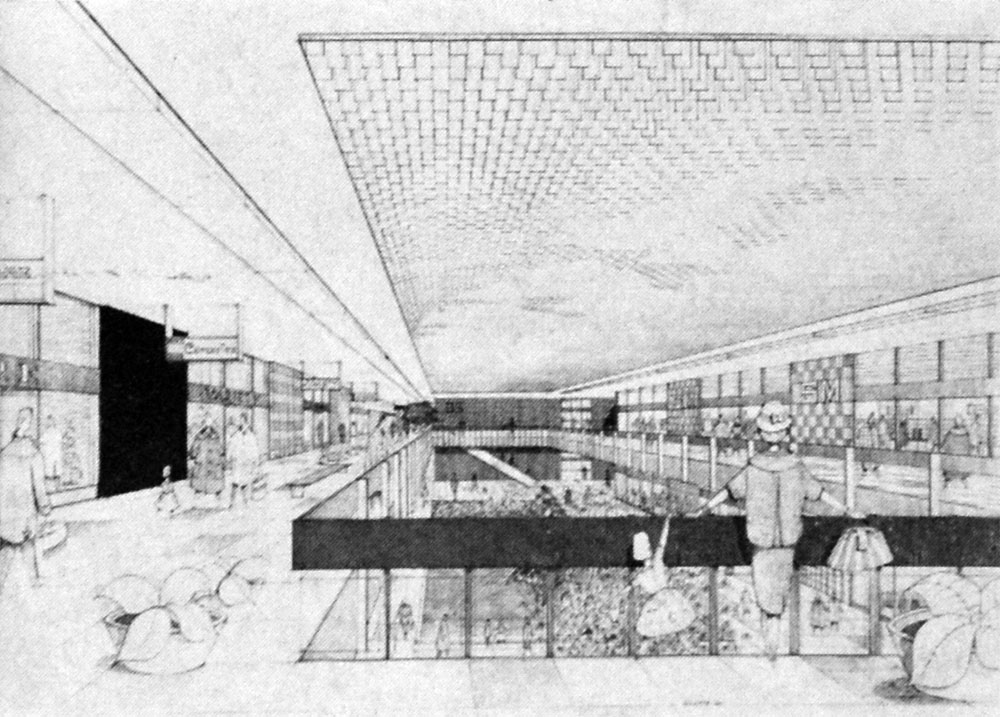

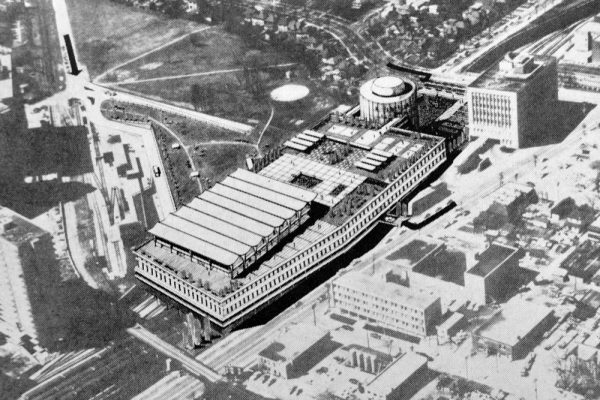

Also in 1960, a Montreal-based development firm proposed the first major “air rights” development in Toronto. The Davisville Shopping Centre was to be built on stilts over the Davisville subway yard, covering almost all of the TTC tracks and buildings.

In exchange for a 100-year lease to build above its property, contractor Anglin-Norcross Corp. Ltd. and its financial backers, Property and General Investments Ltd. of London, agreed to pay between $85,000 and $127,300 in annual rent to the TTC.

Anglin-Norcross had a strong resume: The company was providing heavy construction work and station finishing on the University subway line, and in the past it had been the general contractor on Toronto City Hall, the O’Keefe (now Sony) Centre, and, through a Quebec subsidiary, Moshe Safdie’s Habitat at Expo 67.

The proposed$12-million Davisville Shopping Centre complex was designed by renowned post-war Modernist architect Peter Dickinson, who also designed the towers in Regent Park South, the Inn on the Park, and the CIBC Tower in Montreal, which was briefly the tallest building in Canada.

Dickinson also designed the O’Keefe Centre while on staff at the firm Page and Steele, a project that likely provided the link to Anglin-Norcross.

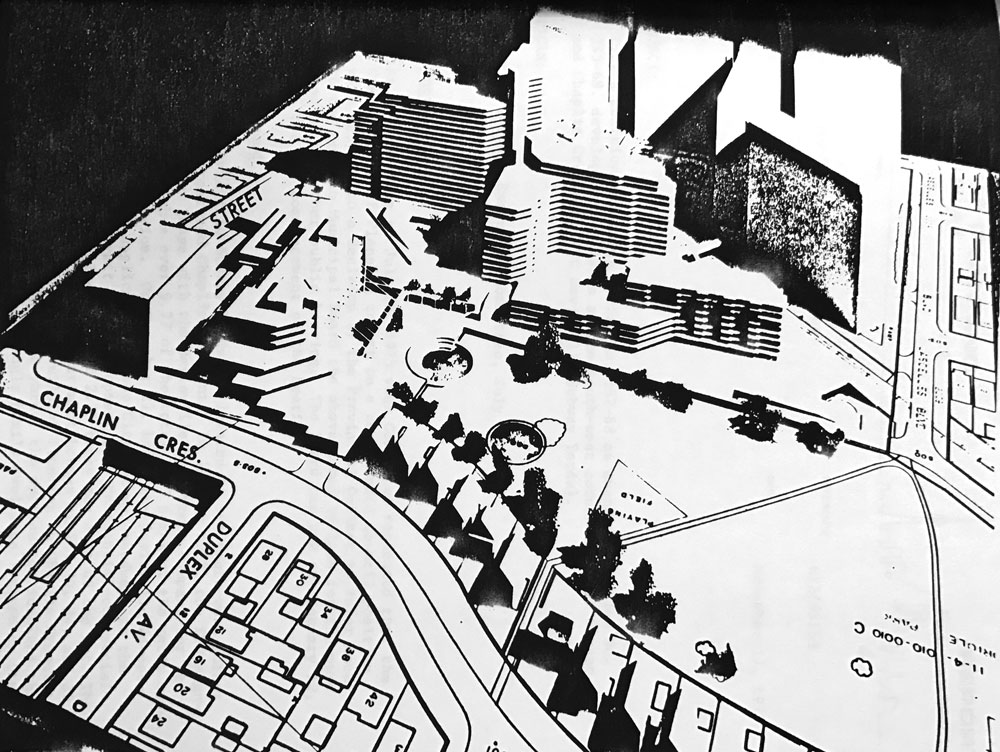

The blueprints and scale models promised 37,200 square metres of indoor, air-conditioned shopping over two levels and parking for 1,000 cars. In total, the mall contained space for 80 stores and room plus an anchor department store over four floors.

A swimming pool, tennis, and other recreation facilities were positioned on the roof adjacent to a circular, seven-storey office building.

The proposal continued to percolate over the next few years without any construction taking place. Despite the lack of tangible progress, the TTC received monthly lease payments from Anglin-Norcross until the company suddenly went into bankruptcy in 1967.

The action placed dozens of projects worth about $100 million in jeopardy. In Toronto, the company had a contract to finish four stations on the under-construction Bloor-Danforth line in addition to the Davisville Shopping Centre project.

On top of the developer’s financial concerns, local residents were beginning to organize against the project. In 1964, the Toronto Planning Board released a series of recommendations against the increasing amount of high-rise and commercial development in the North Toronto area.

The Globe and Mail report on the planning study said the appraisal was “designed to re-establish confidence and security in a predominantly Anglo-Saxon area that had been torn by speculation.”

“Without long-range planning and control,” the paper explained, “North Toronto could become a community of streets lined with monolithic apartment towers as far as the eye could see, giving a total impression of a human tank farm.”

In 1967, a new developer, David Dennis, bought the air rights to the development from the bankrupt Anglin-Norcross and architecture firm Webb Zerafa Menkès Housden produced a new set of designs.

Peter Dickinson died of cancer in 1961 and Webb Zerafa Menkès Housden was the successor to his practice, led by several of its senior associates.

The new design was heavily revised and expanded from Dickinson’s original concept to include four apartment towers of 25, 30, 34, and 39 storeys and an office and retail tower facing Chaplin Crescent. After months of negotiation, this plan, renamed Davisville Centre, was eventually approved by the Ontario Municipal Board in November 1968.

Construction once again stalled in 1971 when the city refused to issue a building permit for the complex because it contained an incinerator for burning used TTC tickets. For safety reasons, incinerators were banned in Toronto apartment buildings in 1967.

In the meantime, an association of Oriole Park ratepayers took up the opposition to the project. With the backing of about 400 neighbourhood residents, the group lobbied the provincial cabinet to block construction on the grounds there had been insufficient public hearing at the OMB.

Rules in place a the time required the OMB to contact only the people living within 120 metres of a development.

Crucially, as the Globe and Mail noted, the president of the Oriole Park Association was Roy McMurty, “a friend and political advisor of Premier William Davis.”

While the OMB and ratepayers prepared for battle, another group of concerned neighbours were complaining to the TTC about noise from the Davisville yard: “A cacophony of squealing wheels, tooting horns, noise from air compressor and the sound of subway motors left running all night,” in the words of the Globe and Mail.

“James Kearns, TTC general manager for operations said the only solution would be to roof the yards, as proposed for the controversial Davisville Centre development—a project opposed by another group of residents from the Oriole Park Association.”

In July 1975, the Ontario cabinet sided with the Oriole Park residents and ordered the OMB to rehear the case. City staff also recommended the project be reduced in size and housing for seniors and families with children included in the blueprint.

Retail in the mall should be limited to supermarkets, restaurants, drug stores, hairdressers, jewellers, dry cleaners, and other businesses needed in the local community, planners said.

Eventually, Davisville Centre fizzled out. In 1979, 21 years after it was first proposed, the design was still on the books at Webb Zerafa Menkès Housden architects without any actual construction having taken place.

Interestingly, the first new building to be constructed over the subway tracks was completed a short distance south, near Summerhill station, in 1970. Despite objections from the Summerville Ratepayers Association and city planners, the city gave the 38 storey tower at 7 Jackes Avenue the green light in 1967.

“A survey by the [ratepayers] association found 261 residents opposed to the project and only seven in favour,” reported the Globe and Mail.

Meanwhile, noise at the Davisville yard is still driving some people crazy.

One comment

So typical. NIMBYs and planners drag out the project until nothing can be built. Instead of shops, residences, recreation, they get a noisy hole in the ground, which at this point is what the residents deserve.

This is a perfect illustration of how “city planning” in Toronto is broken.

This is why we need the OMB, and why we need to get rid of planners.