“I take a walk down Yonge Street,

where good times are bought and sold.”

When folk music great Ian Tyson penned those lines in 1970, he knew his audience would understand. The idea of Yonge Street as the place where the action was — a marketplace in thrills, cheap or otherwise — resonated with a whole generation of Canadians. A walk along Yonge, with its neon lights, crowded sidewalks, and seedy charm, was a defining part of the Toronto experience of the 1960s and 1970s. It was the city’s most popular street, but also its most controversial. By the time Tyson sang about it, the good times on offer had expanded to include a whole catalogue of sexual entertainments and services, from topless go-go dancing to nude body rubs. Toronto soon found itself caught up in a wide-ranging debate over sin, censorship, and the future of one of the city’s iconic public spaces.

From Main Street to Sin Strip

Yonge Street has always had a special status in Toronto. For most of the 20th century, the stretch of Yonge between Gerrard and Queen streets was both Toronto’s main shopping district and the heart of the city’s popular entertainment scene. In the face of urban growth and suburban competition, one of the ways it stayed relevant was by adapting to the times. In the 1920s that meant movie houses and Vaudeville; post–1945 it was cocktail lounges with jazz combos, slowly giving way to taverns serving draft beer and a growing rock and folk scene. From that perspective, the shift towards selling sex was really nothing new. The 1960s were an era of both sexual revolution and “porno chic.” In cities from San Francisco to Montréal, entrepreneurs realized there were huge profits to be had commercializing these trends, and there was very little that local authorities could do about the phenomenon as obscenity and prostitution laws loosened or were struck down.

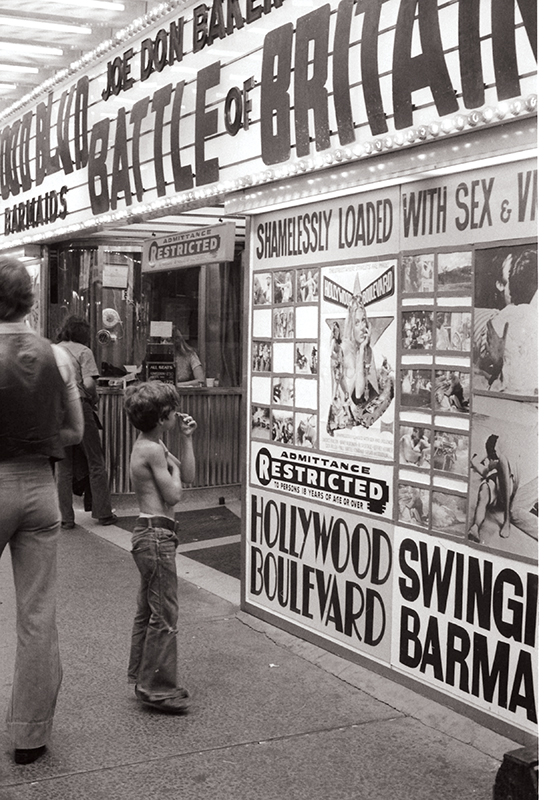

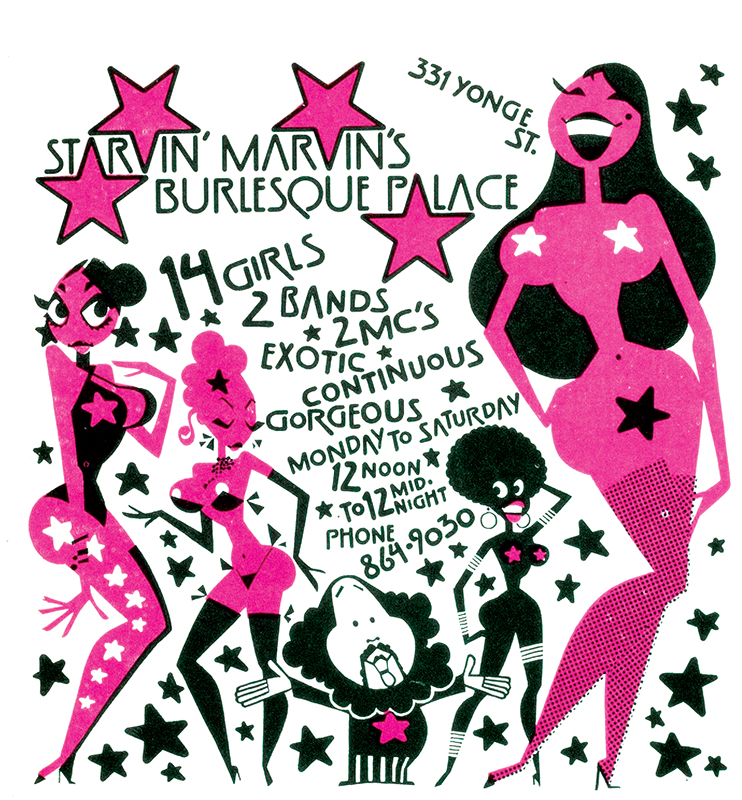

Beginning around 1969, sex changed from being a minor sideline on Yonge to one of its defining commercial activities. First-run movie theatres switched over to grinding out B-movies like Vampire Vixens at all hours of the day and night. One adult cinema catering to the “raincoat brigade” became nine, and peep show booths and adults-only sections appeared in bookstores, discount shops, and the backs of arcades. Established bars and music clubs began to advertise topless go-go dancers, while touts patrolled the pavement in front of several new clubs promising fully nude strip shows. Beginning in 1971, dozens of body-rub parlours opened in cramped second- and third-floor locations, advertising private stripteases and nude massages while hinting at the sexual availability of attendants. In bars, on the sidewalks, and at the 24-hour snack counter of Ford Drugs, prostitutes discreetly waited for clients among the milling crowds.

Nearly all of these new activities were concentrated in the stretch of Yonge between Gerrard and Dundas streets, earning those four blocks the nickname Sin Strip. Like other sex districts across North America, it was a playground for heterosexual men, where they paid to experience the pursuit of sexual pleasure. Because the sex industry sat next to (or even shared space with) other businesses — bars, theatres, restaurants, retail — men were by no means the only people thronging the Strip, but in the body-rub parlours and strip clubs the relationship was obvious: women worked, and men consumed. Society’s new leniency towards explicit entertainment generally did not extend to depictions of the male body, or to gay sex.

Some women found working as a dancer or body-rub attendant empowering; others thought it was degrading, or simply a means to an end. There was certainly money to be made. In 1973 one body-rub attendant told an interviewer that she earned $300 (about $1,500 in today’s dollars) a week; meanwhile, the operators of area strip clubs and body-rub parlours claimed to be raking in ten times that amount. That pleased their landlords, many of whom were able to charge market rents for run-down properties they were holding in speculation of future redevelopment.

Big-city thrills or urban decay?

Sin Strip’s entrepreneurs were able to boast about their acumen because the public seemed to have an insatiable curiosity for their trade. Beginning in 1969, a series of journalistic exposés introduced readers to the dangers and delights of “the Times Square of Canada.” Reporters described taking in a strip show at Zanzibar, feeding quarters into peep show booths, or thumbing (disinterestedly of course) through dirty magazines. A few took the plunge and dished out for nude body rubs — one was even offered “extras” by his matter-of-fact masseuse. The tone was generally positive, as if to say that Toronto had nothing to fear from a bit of big city sleaze.

That changed around 1972. Summer experiments in pedestrianizing Yonge Street were successful in bringing people to the area, but they also made the scene on the Strip more volatile than usual. Bigger crowds meant more business, but also rowdier behaviour, an increase in on-street prostitution, and more broken beer bottles to tidy up on Sunday morning. By winter of that year, a local merchants’ organization, the Downtown Council, was calling on City Hall to help clean up some of the worst excesses of Yonge’s new businesses, and newly elected Mayor David Crombie promised action. Suddenly the idea that Sin Strip was a problem requiring a solution became the subject of serious debate.

Leading the charge were Toronto’s evangelical Christians. In places of worship across the city, ministers preached that Yonge was “Toronto’s Sin-lane to ruin,” and encouraged their congregations to put pressure on their elected representatives. Meanwhile, a newly minted populist tabloid, the Toronto Sun, mobilized conservatives of all stripes with its calls for a crackdown on Sin Strip. Crombie found himself inundated with letters from concerned citizens. By March 1973 he had heard from nearly 1,000 Torontonians — the most mail received by a Toronto mayor on any single issue for decades.

Both the Sun and evangelical Christian activists tapped into a powerful reserve of frustration with their anti–Sin Strip campaign. Whether they framed their objection in terms of Christian morality or simple common sense, many Torontonians felt that 1960s permissiveness had gone too far: legalized abortion, widespread drug use, decriminalized homosexuality, and now smut. In the early 1970s, conservatives in Canada, like their counterparts in the United States, often saw themselves as a “silent majority” under assault. Alongside frustration, there was fear. Looking to the United States, people wondered whether the appearance of Sin Strip wasn’t a sign that the so-called “urban crisis” had finally arrived in Toronto. They imagined post-apocalyptic futures for the downtown core — inspired by the worst aspects of 1970s Detroit and New York — if the authorities did not take a stand.

But opposition to the sex industry on Yonge was about more than frustration with cultural change or fear of urban decline. Torontonians from neighbourhoods across the city felt a powerful sense of ownership of the street and resented that a few unsavoury characters could interfere with others’ enjoyment of it. These Torontonians saw the issue in terms of rights: their right to stroll down Yonge unmolested by touts, or their right to bring their children to Yonge and Dundas without having to explain what a reverse rub — or a total massage — was. “Yonge must be for all the people,” wrote a citizen in the Toronto Star, and it should not cater to a fringe minority.

Of course, rights could cut both ways. The possibility of City Hall “cleaning up” Yonge enraged defenders of civil liberties. Mature adults had the right to patronize body-rub parlours and strip clubs, and to choose for themselves what to read or watch. Anything else smacked of dictatorship, explained celebrated writer Pierre Berton in discussion with reporters. Taking another tack, critics of the cleanup idea argued that Toronto wouldn’t be the same without Sin Strip; it was one of only a handful of colourful, exciting areas in the otherwise dull and repressed Toronto the Good. There was a bit of suburban-downtown resentment, too: “Imagine for a moment,” explained one man to the mayor, “all Toronto as bland as its suburban areas — a big city needs its Strip.”

Torontonians lined up on both sides of the question, and while opponents of the Strip were certainly more vocal and organized, by the end of 1973 the debate seemed to be at a stalemate. Yonge’s body-rub magnates could breathe easily for a while. But even with a clear mandate, just what could authorities do about vice on Yonge? Municipal powers were limited, and the federal government appeared to have washed its hands of intervening in local debates over censorship and prostitution. Watching the gears turn as Toronto and Metro officials explored their policy options was a lesson in political improvisation.

When questioned, Police Chief Harold Adamson explained that his hands were tied. Charges against Sin Strip businesses rarely held up in the increasingly lenient courts, and the most flagrantly illegal activity on the Strip — the selling of sexual services in massage parlours — was difficult to prove without costly undercover stings and raids. In a period of rising crime rates and national concern over the drug problem, his officers had better uses for their time. The idea of using zoning law to disperse or move the sex industry, tactics already implemented in Detroit and Boston, was initially attractive. But drafting the law was bogged down by legal complications and by squabbles over which city neighbourhood should host the new sex district (King and Parliament streets and the Island were two suggestions).

By 1974 the success of Sin Strip had inspired imitators, and dozens of body-rub parlours were opening up across the city, peaking at around 100 in 1975. This rallied suburban voters and politicians, like former North York Mayor Mel Lastman and Metro Chair Paul Godfrey, to the cleanup cause. It also gave Metro Council a mandate to act, even if the City of Toronto was still dithering about civil rights and censorship. Within a year, Metro passed a law that effectively tried to license massage parlours out of existence. Only 25 licences would be granted, and licensed establishments would have to close at 1 a.m., submit to health inspections, and pay an exorbitant annual fee.

The 1977 crackdown and its aftermath

Neither policing, zoning, nor licensing could do much on its own without a significant amount of public support and inter-governmental cooperation. The stalemate continued until a series of developments in the summer of 1977. In June, Toronto City Council published a scathing report on Sin Strip, alleging that it had deep links to organized crime and calling it a problem that “if left unchecked, could permanently damage this City.” And just two months later, the body of 12-year-old Emanuel Jaques was found by police on the roof of body-rub parlour Charlie’s Angels. Jaques, who worked as a shoeshine boy near Yonge and Dundas, had been raped and murdered by four area men, three of whom worked at the parlour doing odd jobs and security.

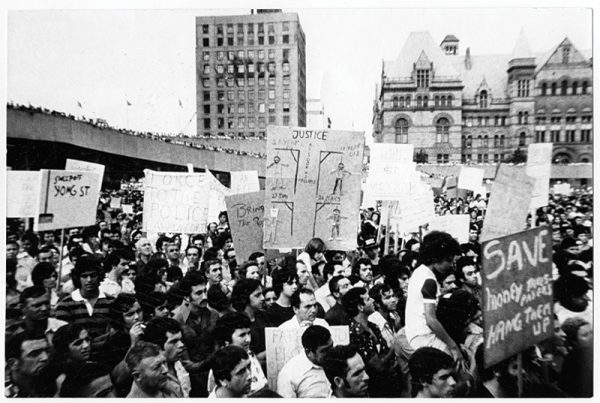

Torontonians were shocked by the crime. Coming as it did on the heels of Council’s report, Jaques’s death seemed to confirm Torontonians’ worst fears about the dangers of Sin Strip. It also mobilized thousands of people who had previously been silent. A few days after Jaques’s public funeral, a crowd of nearly 15,000 — many carrying banners and signs in Portuguese — marched downtown to City Hall calling for swift justice for the murderers of one of their children. It was a moment of political awakening for Toronto’s Portuguese community and a political opportunity for cleanup proponents like Mayor Crombie. Few people were willing to defend Sin Strip in the wake of such a gruesome crime, and the Province and the police came under enormous public pressure to devote extra resources to shutting the area down. One of the mayor’s advisors summed the situation up succinctly: “Three weeks ago Crombie was a fascist for trying to clean up the street: now he’s ineffectual for not doing it sooner.”

The crackdown on Sin Strip that followed was ugly and excessive. In the course of a few weeks, dozens of police raids and 200 City inspections led to hundreds of criminal charges and licensing violations for sex shop operators and employees. Even when cases fizzled out in the courts, the message remained clear, and by the end of October 1977, 36 out of 40 sex shops on Yonge had been hounded out of business. Stalwarts like Zanzibar remained untouched, and some of the peep shows quietly re-opened; but the body-rub parlours and the anything-goes atmosphere of Sin Strip had all but vanished.

After 40 years of revitalization programs, streetscape improvements, and (above all) massive private redevelopment, today’s Yonge Street bears only a few traces of Sin Strip. The venerable Zanzibar and newer additions like Remington’s continue to buck the trend towards strip club closures, and a sprinkling of sex shops offer the latest in stag party favours, toys, and adult film. But, in marked contrast to the 1970s, no one really seems to care. If Yonge is under the microscope today, it’s for entirely different reasons: nostalgia for the era before the Eaton Centre and big chain stores (witness the debate over the iconic Sam the Record Man sign) and the return of that perennially good-but-unimplemented idea, downtown pedestrianization.

Looking back on Toronto’s debate over Sin Strip, it’s striking how loud it was, but how little it really resolved. As in so many of our campaigns to rid ourselves of vice, the practices causing the controversy were not eliminated, just displaced. Commercialized sex never reappeared in Toronto with quite so much verve and attitude — or in such a concentrated space — but it did come back. Somewhat ironically, Metro’s licensing regime (still more or less in place today) would provide a framework for the continued dispersal of body-rub parlours to drab strip malls and storefronts throughout the city. Out of sight, out of mind, but maybe that was the point. Toronto was willing to tolerate the sex industry — just not on its main street.

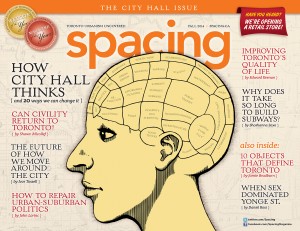

This story originally appeared in Spacing‘s Fall 2014 issue. Daniel Ross is an urban historian and an editor of ActiveHistory.ca.

This story originally appeared in Spacing‘s Fall 2014 issue. Daniel Ross is an urban historian and an editor of ActiveHistory.ca.