In December 1954, the railway tracks near Logan Avenue presented the final obstacle in one of Toronto’s first major post-war road building projects—the construction of Dundas Street East through the east end of the city.

At the time, Toronto lacked a direct route through the area east of the Don River that wasn’t already dense with streetcar traffic. At the time, most drivers used Keating Street in the Port Lands, which was was the primary waterfront route before Lake Shore Boulevard, in an effort to avoid the Danforth and Gerrard and Queen streets.

In 1950, the Toronto Planning Board observed that Keating was almost at capacity during rush hour and new roads would be needed to handle the expected boom in vehicle traffic.

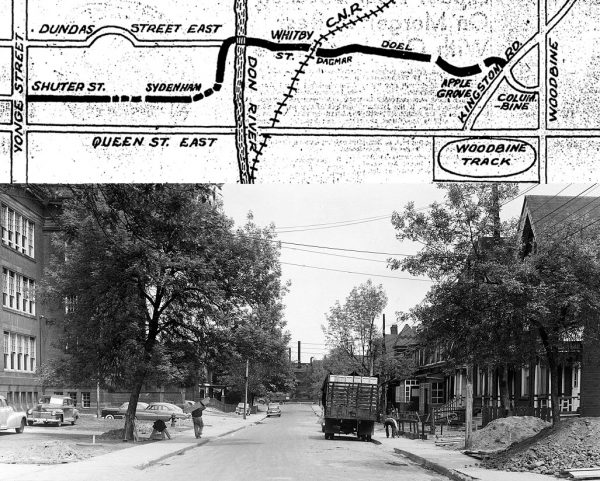

The solution was to create a new highway by widening Shuter Street, which at the time ended at Sherbourne Street, and extending it to intersect with River Street.

From there, the new highway would jog north to connect with a new Dundas Street, constructed out of several formerly disconnected residential streets between Broadview Avenue and Kingston Road.

To extend Dundas, houses would be expropriated and demolished and in some cases whole streets razed and removed from the map.

The budget for the Dundas Street East extension was set at $3.2 million in 1950.

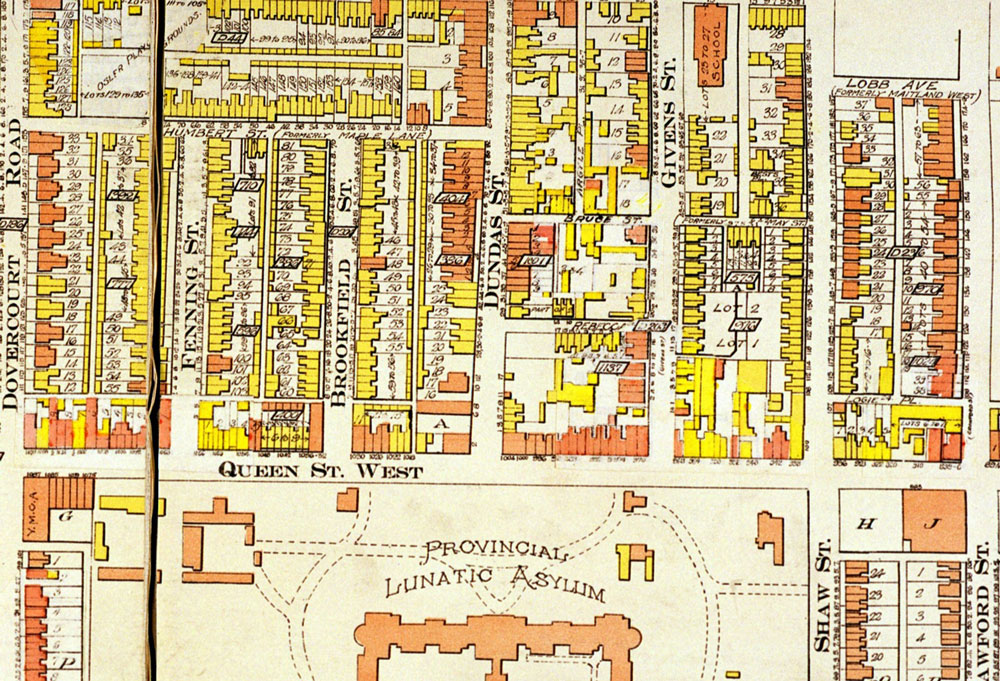

Historically, Dundas Street has always been a hodgepodge. 100 years ago, the street snaked into Toronto from the towns to the west via the Junction, turning sharply south at present-day Ossington Avenue to terminate at Queen Street West.

Dundas became an east-west street beyond Ossington when the city decided to rename and merge several existing east-west streets in 1917. Arthur (Ossington to Bathurst,) St. Patrick (Bathurst to University,) Agnes Streets (University to Yonge,) and Wilton Avenue (Yonge to Broadview) were all linked together and united under one name.

To make the connection possible, the new road had to swerve and bend in unusual places, like on the eastward approach to Bathurst Street. At McCaul Street, Dundas still does a little zig-zag, highlighting how its constituent parts sometimes didn’t line up and had to be cobbled together.

The most famous Dundas Street jog is at Yonge Street, which eventually led to the creation of Yonge-Dundas Square.

Work began on the Dundas Street East Extension began 1950.

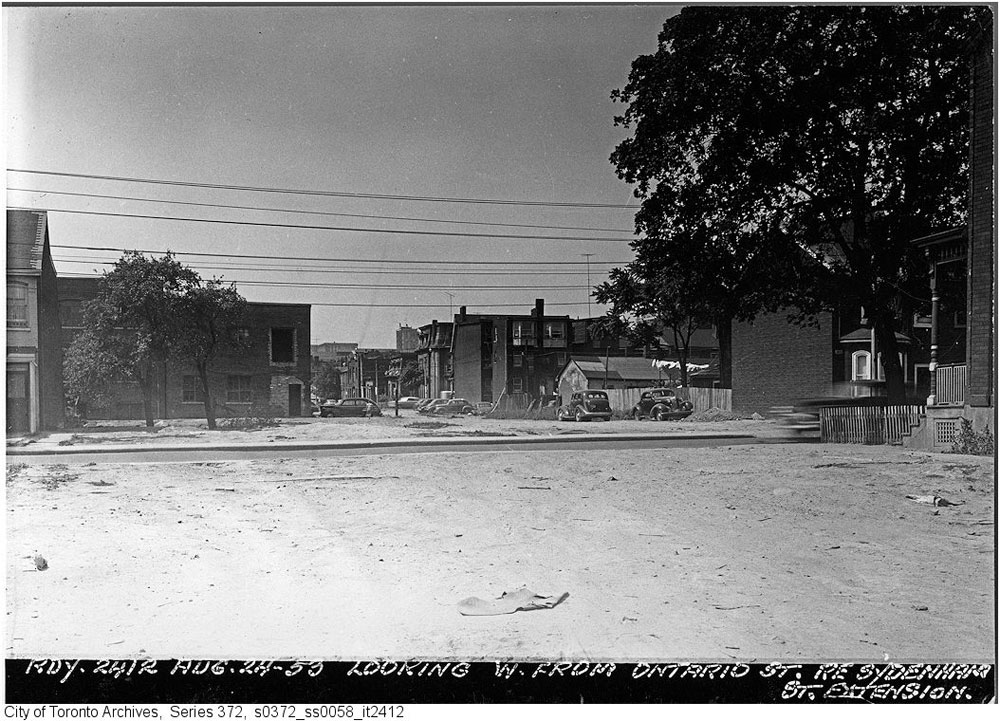

One of the first streets to meet the wrecker was Norvale Avenue, a short residential cul-de-sac of about 14 homes in the Regent Park area. Most of the residents were low-income renters and many of the homes lacked furnaces or baths.

The street was typical of those in the Regent Park at the time. The housing was dilapidated and many of the residents were living in extremely poor conditions.

Residents of Norvale interviewed by the Globe and Mail were worried they wouldn’t be able to find a new place to rent once their street was cleared.

“Homes for our children are more important than an old road,” said Mrs. Martin, a 10-year resident of the street. “It would be different if they were building apartments—but just a plain road…”

Another key concern for Regent Park was the plan to run the new highway directly past Park Public School, one of the largest schools in the city at the time with about 1,000 students.

“This atrocious plan will deliberately divert rush-hour and truck traffic to run in front of this large downtown school,” read an editorial in the Globe and Mail. “It flies in the face of all good planning practice in more enlightened cities.”

Despite the objections of local residents and the media, Norvale Ave. was demolished in 1950 Shuter Street extended right past the main entrance to the school.

A similar story played out east of the Don River.

To create Dundas Street, the city planned to stitch together and widen approximately nine east-west residential roads. The pushback against this plan was mostly centred around the future intersection of Dundas and Kingston Road.

There, the owners of 17 homes near the south end of Edgewood Road urged the city to redirect Dundas up a nearby ravine to intersect with Kingston Road further north, closer to St. John’s Norway Cemetery.

The Edgewood Road homeowners appealed to the Ontario Municipal Board, the provincial body that decides local planning disputes, but lost.

Rather than let his property be demolished by the city, the owner of a drugstore in the path of Dundas arranged to have his building picked up and shifted a few lots to the north, where it remains (seemingly under the same ownership) at the corner of Tompkins Mews.

Work on Dundas Street East ramped up in 1952 with the demolition of dozens of houses east of Broadview Avenue. In a handful of cases, workers knocked down just enough homes to squeeze the road through, creating a number of oddities in the streetscape.

Near Jones Avenue, Dundas took the path of an old laneway, which produced a strange streetscape lined with garages and back back fences.

Nearby, two semi-detached houses were sliced in half at 33 Dagmar Avenue (pictured above) and 115 Brooklyn Avenue (pictured below), leaving blank internal walls facing the sidewalk.

The same scenario played out at Pape Avenue (pictured further down) where a convenience store and half of semi-detached home were expropriated and knocked down to allow the road through.

Once-generous front yards along the new Dundas Street were trimmed back to accommodate additional width of the new, four-lane road.

The missing link in the Dundas Street East Extension was a necessary underpass at Logan Avenue, which was constructed starting in 1953, several years after construction began.

A year later, the new highway opened to auto traffic. Unlike today, it was set up like major arterial—two lanes in each direction, no street parking, and no bike lanes.

At the intersections of Dundas and River and Dundas and Coxwell, the city added special feeder lanes that allowed through traffic to bypass traffic lights.

The city had big plans for the new Dundas Street East. In the 1950s, the new intersection of Dundas and Kingston Road was eyed as the potential east end of the Gardiner Expressway.

In the 1950s, when the city was planing its waterfront expressway, one of the proposed routes suggested carrying the road north from the Lake Shore to meet Kingston Road and Highway 2. The idea had the support of Metro Chairman Fred Gardiner, who also supported removing streetcars from Kingston Road to improve the flow of cars.

It never happened, of course. And now, more than sixty years after it opened, the city is increasingly taking steps to scale back the Dundas highway. East of Broadview, the road has pockets of street parking and bike lanes, reducing it one auto in either direction.

The feeder path that let drivers dodge the red light at River Street was removed recently.

Shuter Street never became the highway the city hoped, but that’s really for the best.

One comment

It may not be possible to turn a sow’s ear into a silk purse, but the oddity of Dundas Street East can certainly be improved. The entire stretch of Dundas Street East is fully residential – a fact conveniently overlooked by the former Metropolitan Roads and Traffic Department in the 1950’s in its zeal to enthrone “car is king” in Toronto.

It took quite a few years of community advocacy to finally have a reduced posted speed limit (rarely, if ever, enforced by Toronto Police Service) and bicycle lanes installed. It also took many years to finally have the pedestrian-hostile “acceleration lanes” removed from both the Jones and Dagmar Avenues intersections.

Not only were some homes demolished, front yards, and some back yards obliterated, many mature trees were destroyed creating a true heat island with this imposed wide expanse of asphalt and concrete. To-day, with ever increasing temperatures because of climate change effects, the absence of these trees and their cooling shade is testimony to political folly.

Unfortunately, political interest appears to be absent and unwilling to entertain ideas on how this former highway can be re-designed to reflect its residential character. With all the concerns to-day about water run-off because of large expanse of impervious asphalt and concrete, this intransigence is inexplicable.

Now with bike lanes, there are some dead zones in the middle of this street in a few areas where central boulevards with trees can be established. Another element just waiting to be developed is to have the sidewalk extended out to the bike lanes in some locations and replaced with open porous surfaces with trees. It’s true a few of the “free” parking spaces would be removed but many of the car owners have space in their back yards to park. Of course, we all know how some folks react when their sense of entitlement is threatened but it seems to me this is a most reasonable trade-off in a world that is getting hotter by the day. .

Having taken away residents’ front and back yards in which to plant trees with their positive ameliorating effects, there are better uses of the public realm than barren asphalt and parked cars. Perhaps someday, we will have enlightened civic politicians who recognize and acknowledge the need to increase our green canopy in these areas to improve both improve our environment and personal health.

Thanks for providing this “history” of Dundas Street East between Broadview Avenue and Kingston Road.

Bill