This is part 1 of a 3-part series on the challenges faced by residents of Toronto Community Housing

Marjorie MacMillan, a retiree who lives in the Toronto Community Housing (TCHC) senior’s apartment at 252 Sackville, stood on the outdoor terrace of her second floor unit and glanced upward. Somewhere, six or seven storeys above, there are tenants who flick lit cigarette butts out the window, and sometimes vodka bottles. “You can’t sit out here,” MacMillan told me on Sunday.

But her concern isn’t just the falling garbage. Not long ago, a cigarette landed on the fabric of one of the lounge chairs on her deck and started to smolder; while a family member put out the small fire quickly enough, MacMillan, who has lived in Regent Park since 1980s and worked in the laundry facility, is now afraid it could have ended badly. She then showed me a small landscaped courtyard just beneath the balcony, a tight space nestled between her building and the adjoining one (photo below). For several years, tenants complained to the building management about the risk of a fire there because the space contained dead pine trees (one branch near MacMillan’s balcony actually did catch fire and a family member doused it). Those were finally removed this spring, but a pile of dead, dry branches and twigs remains.

“I don’t want to get stuck in a fire,” she said, acknowledging she’s not quite sure what she’d do if one broke out. “We’d have to get out somehow.”

You don’t need to spend much time in a TCHC senior’s building these days to find concerns like these. The horrendous blaze in mid-June at the Grenfell housing estate in London, plus more recent incidents, such as a deadly high-rise fire in Honolulu, have made fire risk a top-of-mind concern, especially for TCHC tenants.

Last week, the agency agreed to pay $100,000 in a settlement involving a 2016 fire in TCHC building at 1315 Nielson Road in Scarborough that left four elderly people dead (the corporation was charged with a provincial fire code offense). Elsewhere, an alleged serial arsonist was arrested in May in connection with over 50 fires in another TCHC complex in Scarborough.

At 252 Sackville, meanwhile, the residents I spoke to on the weekend, all of them seniors and some with significant mobility issues, said that TCHC has never developed a fire plan for the 160-unit environmentally friendly building, which was built as part of the Regent Park revitalization effort and opened in 2009. “What we wanted to see was a fire plan,” says Pamela Lalla, who lives on the 22nd floor and organizes senior’s groups. “They have not given us a drill or anything.”

As long ago as 2011, a tenants’ committee wrote to Chuck Dowdall, TCHC’s director of senior’s residences, informing him about “confusion” over exit instructions during fire alarms and the lack of adequate signage in the lobby and parking garage.

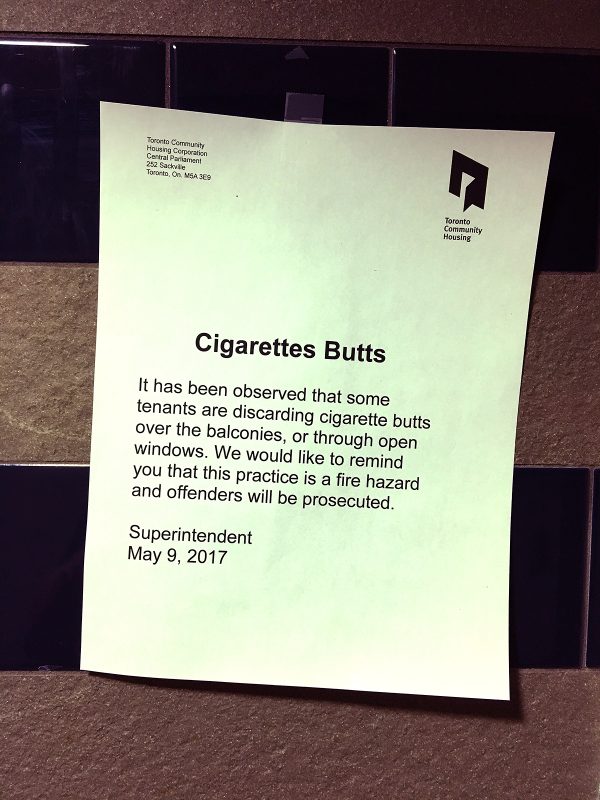

The fire alarm still goes off frequently, I was told, because 252 and the adjoining building have linked heating systems. But besides the standard emergency exit signs, none of the floors seem to have maps with exits and stairwells marked. And while many tenants speak little or no English, the fire emergency stickers posted on the inside of some apartment doors are written only in English. Handbills warning tenants not to toss cigarettes out the windows have been recently taped to the walls around the building.

Lalla also pointed out that there are numerous tenants who are blind or depend on walkers or wheelchairs. Debbie Sperry, who is a double amputee, said no one from TCH has ever told her what to do if a fire breaks out. She also asked for a unit on a lower floor when she applied to move in, but there were none available. “In my opinion, all the handicapped people and the blind people should be on the lower level,” Sperry said. “In a fire, we should be the first ones out.”

It’s hardly the only TCHC senior’s building where frail residents have come to feel especially vulnerable. Connie Harrison, 62, says her 10-storey TCHC apartment, on Victoria Park near Eglinton, is home to many very elderly people with dementia, vision impairment, and physical disabilities.

In the 18 months since Harrison moved in, she said there have been several small kitchen fires, including one when the building’s alarm didn’t go off. The 40-year-old complex is on TCHC’s list of nearly derelict apartments, and is home, she told me, to several tenants with hoarding disorders.

It’s by no means clear how TCH superintendants and building managers handle the task of informing tenants about fire safety protocols and the aftermath of incidents. According to TCH spokesperson Brayden Akers, the agency tries to keep its residents abreast of these issues. “We’ve partnered with Toronto Fire Service for the last couple of years to deliver fire safety related materials and building meetings to targeted buildings,” he said in a statement. (TCHC said it has now implemented a fire safety plan for its property at 1315 Nielson, where the four seniors died.)

But Harrison said a fire safety meeting set for her building (on the day of the Grenfell fire, by coincidence) was canceled without warning, and has yet to be rescheduled. “I’m afraid that one day I’m going to have to pack up and run,” stated Harrison. “I don’t keep anything valuable here because it’s unsafe.”

Lalla and other residents of 252 Sackville told me that TCH hasn’t organized similar information sessions for their apartment, although TFS personnel have distributed stickers telling people to stay in their units in case of a blaze.

At a time when anxiety about high rises and fire safety are running high, especially among vulnerable people like low-income seniors or those with disabilities, such oversights and omissions by a municipal agency seem particularly disturbing.

Not to mention financially risky for an organization consumed with intense cost pressures: While the judge in last week’s settlement handed down the maximum fine (of $100,000), the story of the horrific 2010 fire in at 200 Wellesley, also a TCHC building, offers another potential outcome.

With that case, the blaze broke out in the unit of a tenant with a severe hoarding disorder. In a settlement, the agency offered $4,000 to each of the hundreds of residents forced out of their units after the fire was extinguished. But one tenant, Jo-Anne Blair, was unsatisfied with the sum and launched a class action. Blair’s case led, in 2013, to a $5.5 million judgment against TCHC, with $4.85 million awarded to the 593 tenants who joined the suit, or about $14,500 per unit.

As the presiding Ontario superior court judge noted in the ruling, “Ms. Blair should be thanked for her dedication to the class.”

RELATED POSTS IN THIS SERIES

- PART 1: Are Toronto’s high-rises safe for seniors?

- PART 2: How safe are Toronto’s high-rises?

- PART 3: Does TCHC even know the extent of its fire risk?

One comment

I think Toronto collectively needs to decide if TCHC is something we want to be doing. We draw from the tax pool, to subsidize the living arrangements of 10% of the people in our city, with no priority other than “are you already there?” We have a waiting list that constitutes another 10% of the city; and consequently we’re the owners of the worst slumlord in the city.

I think the citizens deserved to be told/asked “Doing this properly requires spending billions of dollars, which we’re never going to recover. Are you okay if we raise your taxes X amount to do this?”

And if the taxpayers/voters say no: get out of the game. (And if they vote yes, raise taxes and do it right.)

But the middle road we have right now… seems like the worst of all possible outcomes.