Away from the clamour surrounding Jennifer Keesmaat’s departure as chief planner, the City of Toronto has seen another significant, although considerably lower profile, exit with the retirement last week of Lilie Zendel, the long-time manager of Street ART Toronto (StART).

For almost six years, Zendel played a crucial role in transforming a sleepy graffiti eradication program into a sustained effort to bring provocative and vibrant mural art to public spaces, orphaned walls, and traffic boxes around Toronto.

While recent decades had seen a surge of public and artistic interest in graffiti and mural art in cities around the world, especially Europe and Latin America, Toronto lagged, likely due to political parochialism and a generally poor record on fostering imaginative design in the public realm. All that has changed, as evidenced by signature place-making projects such as the Phlegm mural on a Slate Asset Management office tower at St Clair and Yonge, the iconic pillars at Underpass Park, and the soon-to-be-completed Roncesvalles Pedestrian Bridge, by Chicago artist Justus Roe and the local STEPS Initiative.

While recent decades had seen a surge of public and artistic interest in graffiti and mural art in cities around the world, especially Europe and Latin America, Toronto lagged, likely due to political parochialism and a generally poor record on fostering imaginative design in the public realm. All that has changed, as evidenced by signature place-making projects such as the Phlegm mural on a Slate Asset Management office tower at St Clair and Yonge, the iconic pillars at Underpass Park, and the soon-to-be-completed Roncesvalles Pedestrian Bridge, by Chicago artist Justus Roe and the local STEPS Initiative.

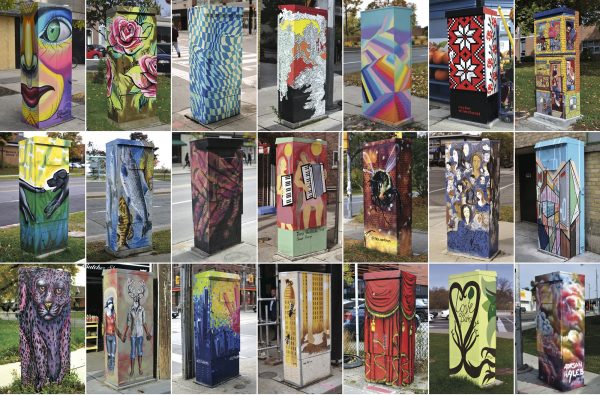

Where many city councillors once looked askance at such works, Zendel in an interview with Spacing last week said that every member of council now wants to see StART projects in their wards. Private landowners, too, are investing in wall murals without the incentive of a City grant. And Toronto has put itself on the map internationally with Outside the Box, a partnership with the transportation division that grew from a dozen traffic control boxes to more than 250. “The reaction from the public has been extremely positive,” Zendel said. She sat down with Spacing to discuss the StART’s legacy and next steps.

Former mayor Rob Ford, Zendel recalled, “was obsessed with graffiti vandalism.” In the early days of his term, Ford staged media appearances showcasing himself with a power-washer, and City staff had to scramble to clean walls. The response, institutionally, was the Graffiti Management Plan, which Zendel describes as “essentially a carrot and stick approach.” Transferred from the culture division, Zendel was given control of a $475,000 social services grant geared at reducing youth unemployment in priority neighbourhoods.

While the program produced murals, the City didn’t look after the works, and, she adds, the art itself lacked verve.

Ford at the time also wanted the civil service to find opportunities to establish public private partnerships. Zendel, who has a theatre background and had done stints at Harbourfront, began to tap into the City’s cultural circles, offering $20,000 grants to community organizations that could bring in more resources. (Eventually, the grants grew to $50,000 to underwrite larger projects.)

The community partners, she said, would generally raise 30% to 40% of the overall budget, with up to half provided in-kind. Zendel and her team added two other conditions: a community consultation process, and the scrutiny of a professional jury that would recommend winning applicants. “No matter how valuable the location,” she said, “the artistic standards had to be really high.”

StART’s Outside the Box program — transforming traffic signal boxes into art pieces — launched in 2012. In recognition of the growing global interest in mural and street art, Zendel’s team soon began inviting international artists to bid, while offering Toronto-based mural artists the possibility of participating in international exchange programs in cities like Chicago.

Despite that orientation, she describes most of the projects as “hyper-local” efforts by a community to reflect something of itself on these “third spaces.” “What I always hope is that [the art] becomes a catalyst for other improvements.”

Zendel doesn’t deny that street art has sometimes accompanied neighbourhood gentrification. But she also stresses that in many cases, especially dimly lit underpasses, the art itself brings improved safety, walkability, and attention from the municipality in the form of better maintenance of orphaned spaces. It also serves as an important counterweight to the ubiquity of outdoor advertising and, by extension, questions of who or what controls public space.

With the program now well established and hugely popular, Zendel says the City faces new challenges, including long-term maintenance of the works (the proponents for each project commit to looking after their murals for five years) and, potentially, the creation of audio tours or other means for better exploring these images, as is done in cities like Philadelphia, Miami and, to a lesser extent, Montreal.

Yet after six years with StART, Zendel also found herself confronting slippery philosophical questions, such as whether there can be too much street art, or whether all public spaces should be seen as potential canvases.

And this: should a work last? There is, after all, an inherent tension in a form that traces its lineage to both the ephemeral nature of graffiti but also the age-old fresco tradition of decorating the outsides of the buildings that define urban spaces. As has happened in places like London, some works of street art become so valuable, and their creators so sought after (see Banksy), that they attain a kind of fetish-like collectors’ appeal which is at odds with both the medium as well as the fluid nature of the city itself.

“When do you think it’s time [for a work] to move on?” Zendel muses. “There’s no clear answer, but it’s an interesting debate to have. As one of my artists said, ‘After all, it’s just paint.’”

Clarification: StART’s mural programs are delivered by the Public Realm Section, Transportation Services to implement the City’s Graffiti Management Plan. Zendel, as manager, oversaw the program with a team of four but did not personally control the funding.

top photo courtesy of Lillie Zendel; middle photo by Ryan Raz; bottom photos by Matthew Blackett

One comment

I wish Lillie the best of luck in the future, and I really hope this ushers in a change for Street Art Toronto. It’s become almost institutional in it’s approach to art with a history of funding projects that don’t create calls to Artists but are cherry picked and handed to the same handful of artists over and over.

The same can be said of some of the “Non profits” who are taking in hundreds of thousands of dollars and either cherry picking artists or using young and newcomer artists who bust their backs for a pittance.

I’d like to celebrate the talk of having an international exchange program with muralists but when has StART sent a Toronto based artist to another city?

Underpass park is another questionable accomplishment, there was one call which was filled with friends of the coordinator, then a cherry picked artist and finally this year a round of pillars completed with no artist call but a mysterious “roster” that artists were somehow chosen from. Maybe it’s like the underpass roster that many artists are on but have never and possibly will never get to propose a project through.

StART needs to be back under the Culture department, I’d even remove funding for a year so the majority of parasitic NFP’s like STEPS, Mural Routes, and Patch could wither away and the artists could get a fair chance at creating.