In the 1950s and 60s, Toronto, like cities all over the world, struggled with challenges delivered by the rise of the private automobile.

For the first time, tens of thousands of cars were descending on the city each day, demanding extra road space, specialized traffic control measures, and places to park.

In early 50s, there were very few high-capacity parking lots in downtown Toronto. There were meters at the curb and plenty of surface lots, but nothing like the multi-storey above and underground garages that are so common today.

That all changed in 1952 with the formation of the Toronto Parking Authority, which was set up by the city to build garages and make money for the city from parking fees.

Prior to the TPA, the police oversaw and managed parking meters in the city, but the focus was on providing storage space, not making money.

“Meters are designed to provide parking, not to raise money for the city coffers,” said Nathan Phillips, who was later elected mayor of Toronto.

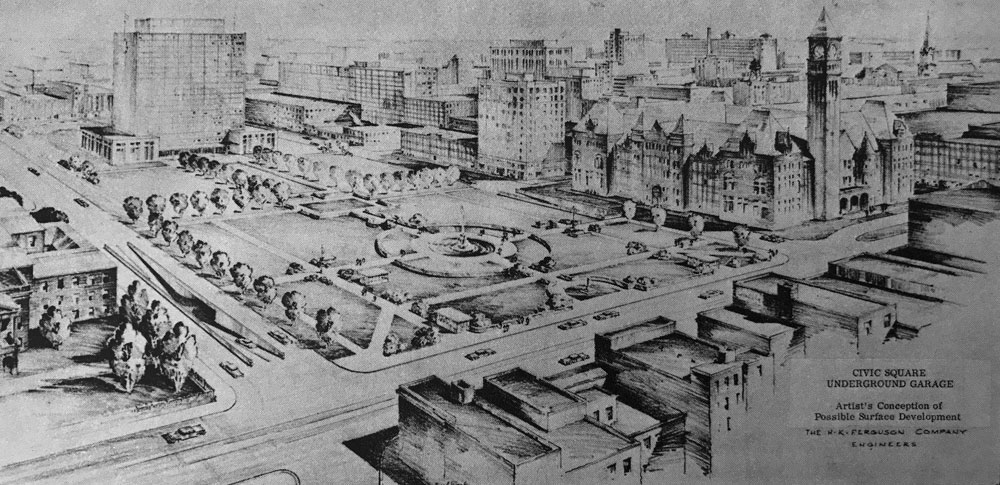

The first garages proposed by the TPA were to be located underground. There was a plan for one under the lawn of Osgoode Hall and the city even hired an architect to create detailed plans for a three-storey, 2,200-space subterranean garage on the future site of Nathan Phillips Square.

The garage would also have doubled as an air raid shelter capable of holding 15,000 people in the event of an attack on the city and it was to be topped by a landscaped park centred around a fountain with manicured lawns and walking paths.

As it happened, the TPA decided their first garages would be multi-storey, above-ground structures. But instead of allowing drivers to pull in on a ramp from the street, the storage of cars would be handled entirely by machine.

The first high-rise, automatic parking garages appeared in the 1930s in cities like Chicago and New York. At their simplest, scaffold-like structures allowed cars to be raised on an elevator and stacked on top of each other when space was tight.

The most advanced automatic parking garage of the age was in Manhattan. The Kent Garage “Hotel for Autos” was a 24-storey skyscraper built solely for storing cars. Vehicles pulled onto a central elevator and were distributed throughout the building’s “rooms” by a rubber tired mechanism that attached itself to the cars’ axels.

The hotel was a financial disaster and it closed after only a few years in operation (the tower is still standing and it has since been converted into condos.)

High-tech parking facilities became a topic of discussion again in the 1950s. In an Atlantic piece titled “Parking in the Sky”, prominent New York real estate developer William Zeckendorf outlined his solution to the problem of parking in the age of the automobile.

“The only real solution to the critical downtown parking problem in the central city is a vertical solution,” he wrote. “And a vertical solution means a mechanized solution. It does not mean a ramp garage. A ramp garage is old-fashioned and illogical; the Pharaohs used it to build the pyramids.”

Zeckendorf believed auto makers and oil companies should help tackle urban challenges created by their cars, and that Detroit should find a way “to store cars automatically in vertical buildings and recapture them without human labour—to take cars in and put them away very much as an IBM machine files cards and recaptures them.”

When Zeckendorf wrote his piece about six automatic parking garages were already in operation. One of the most famous, the Park-O-Mat in Washington, D.C., opened in 1951 and required only one person to operate. The 16-storey structure contained two large elevators capable of raising and lowering automobiles.

Customers pulled in, left their car in neutral, and an elevator system raised their car to an empty space and shunted it inside using a metal arm. At capacity, the Park-O-Mat could hold 72 cars.

It was this type of system that the Toronto Parking Authority planned to bring to Toronto.

The Toronto Parking Authority’s first multi-storey parking structure was a conventional ramp garage at Queen and Victoria Streets. Completed in April 1956, it contained 450 spaces over three floors, and was the first municipally-owned structure of its kind in Canada.

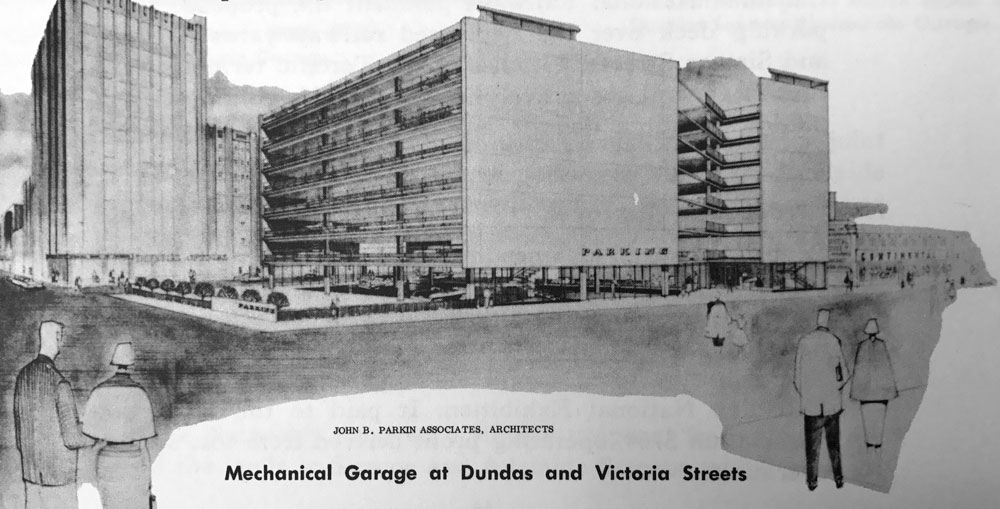

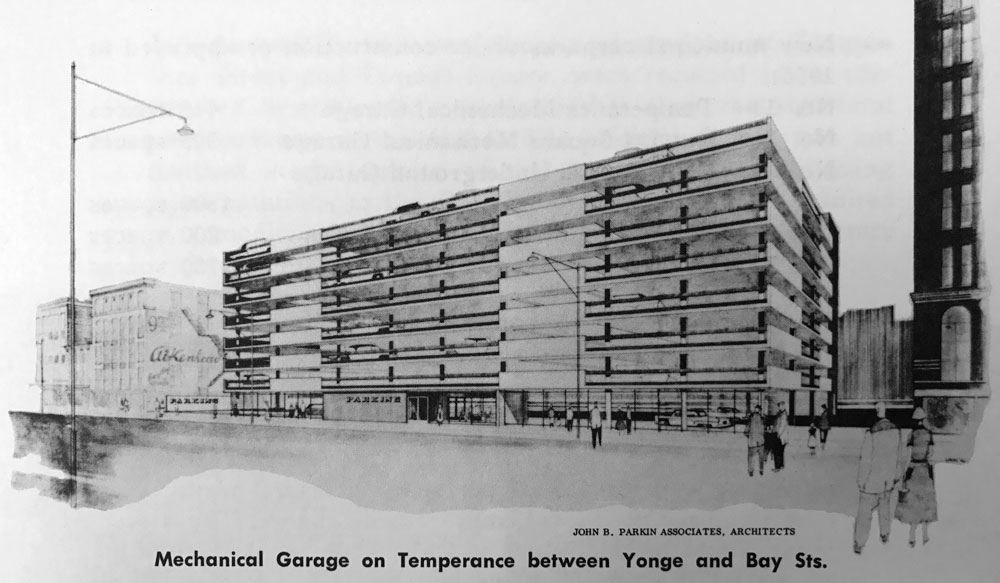

The TPA wasn’t just content to cover the city with conventional garages. In 1956, the authority commissioned John B. Parkin Associates to design two fully-automatic garages similar to the Park-O-Mat: one on Temperance Street and another on Dundas Square.

TheJohn B. Parkin Associates firm consisted of John B. Parkin, his engineer brother Edmond T. Parkin, and John C. Parkin, the partner-in-charge of design, who coincidentally shared a name with the principal of the firm, but was no relation.

John B. Parkin Associates were heavy hitters. They were consulting architects on the Yonge subway line and would later be credited on major projects like the Toronto International Airport, New City Hall, TD Centre, and Ottawa’s Union Station.

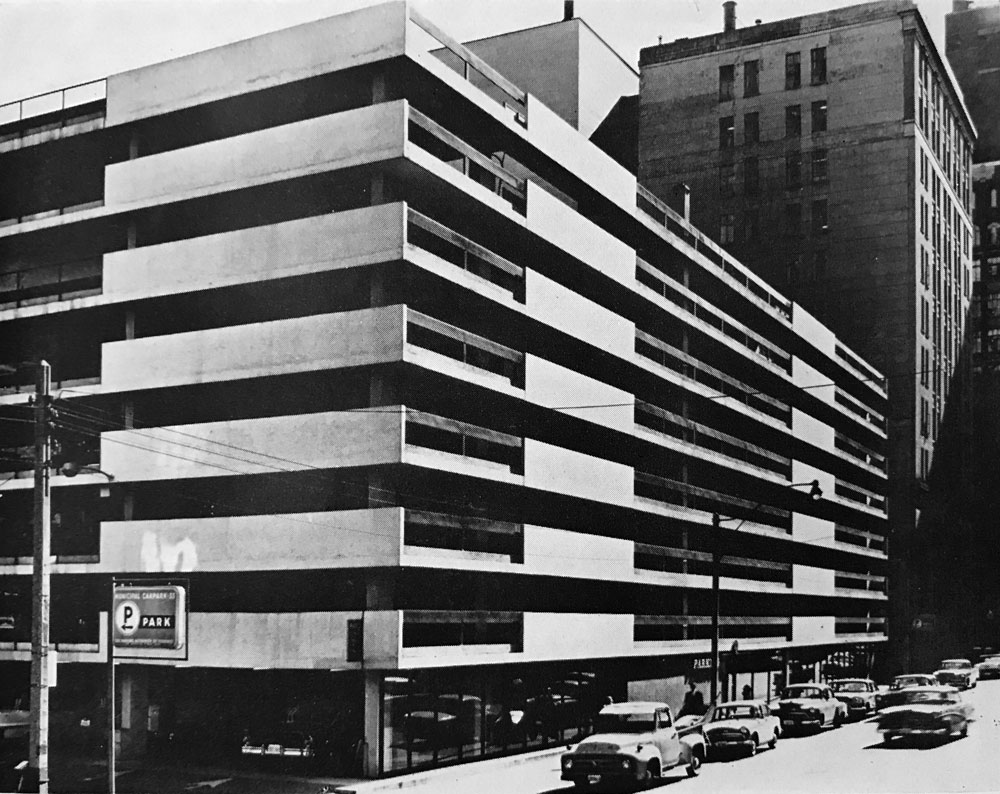

The finished Parkin mechanical parking garages were straightforward reinforced concrete structures, geometric in shape and decorated with ceramic tile and painted bright colours to liven up the exterior.

“The end rails and ceilings, which from the street appear as long, straight, parallel lines have been painted in wildly different colours—yellow, grey, two tones of blue, and fire orange. The street walls have have high panels of striking green tiles,” wrote Globe and Mail columnist Haggart.

“We think they’ll be exciting garages, too, with the motion of the elevators moving up and down,” said John Walker, an engineer with the Toronto Parking Authority.

“We put in plate glass windows so the public can watch the operation … I think it proves that municipal ventures don’t have to be dreary ventures.”

Each of the completed garages, which opened in 1957, were capable of parking a car in approximately a minute, but that could be cut to 30 seconds in rush periods.

“[The] customer drives in at street level, turns off engine and locks the car, elevator comes down, picks up the car on dollies, and whisks it up to some pigeonhole upstairs,” explained columnist Haggart in the Globe and Mail.

“Cars won’t be touched by human hands … from the moment the customer turns the key in his door to the moment he unlocks it again.”

Staffing was minimal: one person operated each elevator and there were three to handle cash. The cost to park was 25 cents for 24 hours, a fee designed to make the garages desirable to the nightclub and theatre traffic, and the TPA expected each parking space would be used three times on average each day.

Despite the hype, the Parkin mechanical garages proved to be a total bust. The lifts frequently broke down, and a year after opening, at no time had all the elevators been working at the same time.

In 1958, the TPA attempted to modify the elevators, but it appears there was little improvement in performance.

“There have been so many troubles I just don’t want to tell you about them,” chairman of the TPA, Ralph Day, admitted to the civic traffic committee in March 1958.

The Temperance garage was operating at around 50 percent capacity, owing to the technical problems, Day explained. The Dundas Square garage was worse, reaching only 20 percent capacity. Both were haemorrhaging money.

In 1965, the Dundas Square lot lost $87,000 and the finances of the Temperance garage were equally bleak, losing $50,000 a year. In 2017 dollars, the losses were equivalent to about a million dollars a year.

Unable to modify the garages to conventional ramp operation, both garages were knocked down in 1965, just eight years after opening. The Dundas Square site became a surface lot and a new ramp garage was built on Temperance Street.

The parking authority hasn’t experimented with automatic parking since.

2 comments

I really don’t understand why we don’t have more towered parking lots with ramps. Seems to me that could remove a huge amount of parked cars off the streets, allowing traffic to flow more smoothly

Self-park garages waste so much space for ramps and maneuvring. There are plenty of manned elevator garages that work fine, even if the robot experiment didn’t work. Ultimately though, parking is incredibly expensive and space-consuming, and not the best use of urban land.