The Unilever Precinct (also sometimes called “East Harbour”) is a remarkable opportunity to create an entirely new business district in Toronto. As an almost completely blank slate, it offers a chance for creating an interesting, original urban space.

And it’s important that the district be interesting and engaging, because drawing people to this new district and integrating it into the rest of the city could be a challenge — it is somewhat isolated, by railway tracks, expressways, industrial lands, and the river, and as an all-employment district the area risks being empty outside of office hours.

A key to creating a vibrant district is public space — the spaces between buildings that shape how people experience the area. The planning for the public space in the district has gone through several phases, and reveals some of the underlying tradeoffs that go into creating public spaces when city-building.

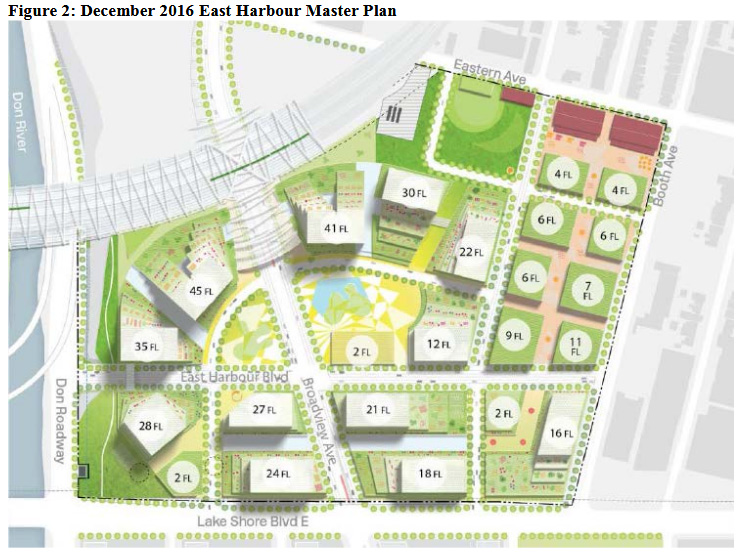

Planning for the district began well before any formal application to the City government. I was part of a stakeholder group that gave feedback on the initial plans as the developer was working on them. The precint was always going to be very dense, so the challenge was creating public spaces that would effectively balance that density.

The final plan that was presented to us was interesting, focused around a major, curving central plaza.

A significant benefit of the plan was that there was, as the saying goes, “a there there.” The area would have a central focus, a remarkable space that would both define its identity and connect its major buildings, while creating a sense of openness amidst the density.

A related benefit was that it was a bit different from the rest of Toronto. I’m normally all in favour of contextual building, but an entirely blank slate felt like a good opportunity to do something new and different, to get away from the relentless Toronto grid.

However, when City planners saw the plans, they noted some significant issues, including:

- The plan would demolish the existing main factory building on the site. As an attractive building that links the site to its industrial heritage, that building also provides some definition and identity.

- Although an extended Broadview Avenue would be the district’s main arterial, none of the buldings actually fronted on Broadview.

It was also pointed out that, during the many years of the construction phase, the large plaza would feel open to the elements and somewhat desolate. It wouldn’t perform its function fully for a long time. (This information is based on discussions with City and First Gulf staff at consultations).

So, when the plans were presented to the City for formal approval, they turned out to be completely different. The outstanding issues were addressed: the old building was maintained, and most of the buildings were now oriented along Broadview.

The problem was, the advantages of the original plan were lost. The area now lacked any kind of central focus, and looked much like any other rather dull office building district, with tall buildings lining straight streets. Any distinctive identity provided by the old building was marginalized to the western edge and cut off from the main artery along Broadview.

Public space had likewise, as so often happens in Toronto, been mostly relegated to the margins. The parks were on the edges of the plan and the main plaza around the old building (far left) was wedged between tracks and the river’s flood berm and was disconnected — placed behind the main buildings, with poor, narrow connections to the main street. The public spaces east of Broadview, meanwhile, were straight lines wedged between buildings.

With the exception of Yonge-Dundas Square and a few others, Toronto often treats its parks and plazas as places to escape the city, rather than putting them in prime circulation areas to improve and connect the city experience. We often talk about envying European cities, but we too often ignore their example of centering a district around an open public space.

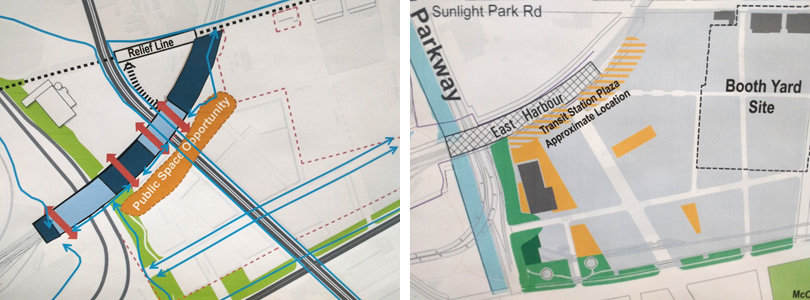

However, in the public consultations that followed, a solution suggested itself in a point of tension between the diagrams provided by the City and those of the developer. The City envisaged a “transit plaza” along the south side of the planned “SmartTrack” station — an open space that would greet people disembarking from the commuter trains. It would also provide a visually open, inviting connection between the Broadview corridor and the main plaza area around the old building. As well, it had the potential to provide an orientation and welcoming space to people walking or taking transit down Broadview and through the tunnel under the tracks to the new precinct (for example, from the planned relief line station further north). As the first thing most people would see when they arrive at the precinct, it could define the area if done well.

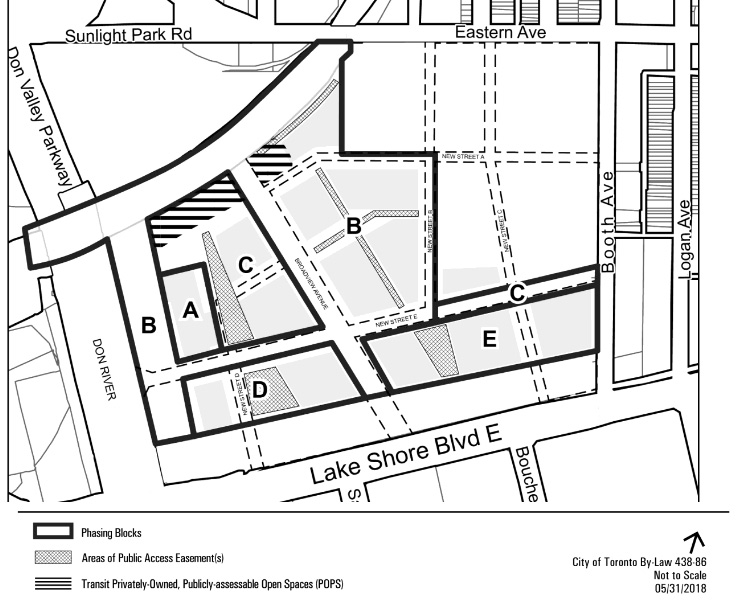

After the review and consultation process, the final plans approved by the City do include a provision for an open transit plaza space in front of the SmartTrack station and Broadview tunnel, but its exact configuration remains vague. The zoning by-law amendments (PDF) say:

Prior to Site Plan Approval for the lands referred to as Phase C on Map 7 , the owner shall provide a plan for outdoor space acceptable to the Executive Director and Chief Planner, City Planning, that provides for a minimum of 2,000 square metres of contiguous open space located generally within the hatched Area 2 of Phase C on Map 8.

Here is Map 8

It means there’s a potential to have a “there” there, for the Unilever precinct to have some kind of distinctive identity and some unity in its public spaces, but it’s only a portion of the hatched area above so it’s not really clear if in practice it will be enough to serve this purpose. Even if it does, it’s not as dramatic as the original plan, so the role of providing identity might have to be supplemented by architecture — will those tall buidlings be dull, square glass blocks (as in the renderings), or will they have some kind of interesting, attractive — perhaps even jointly coherent — appearance that will grace Toronto’s skyline and provide interest and excitement at ground level? The fate of the Unilever precinct — dull office maze or distinctive new destination — hangs in the balance of decisions still to be made.

An accidental reference to Crosstown has been corrected to SmartTrack. Thanks to Jason Paris for the catch.

Images from City of Toronto documents