Earlier this week, Mayor John Tory and mayoral candidates Saron Gebresellassi, Knia Singh and Jennifer Keesmaat debated transit, affordable housing, safety and other topics at a Black community issues debate in Scarborough. But one of the main issues they discussed was anti-Black racism in Toronto.

That broad conversation speaks directly to the intimate and provocative work of Janice Reid, and her first photographic exhibit, presented by Black Artists Network in Dialogue (BAND).

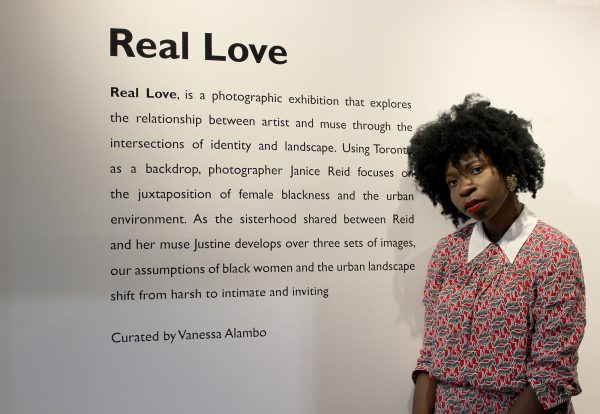

The show, “Real Love,” is on display at the BAND Gallery & Cultural Centre (19 Brock) until October 7. In an exhibit curated by Vanessa Alambo, Reid’s photographs not only explore the relationship between Black womanhood, sisterhood, and the body; it also invites viewers to think about the counter-narrative to stereotypes of Black womanhood that circulate in the media and the intersections of these issues in a space that is led by the vision of other Black women.

Located at 19 Brock Avenue, BAND has become a hub for Black image artists. Under the leadership of Karen Carter, who is also the founding executive director of Myseum of Toronto, BAND has become a space for visitors to reimagine the parameters of blackness in the city. Real Love is no exception.

In a talk last weekend, Reid said that one of the biggest inspirations for her project came from just being Black, a woman, and proud to have been born and raised in the Jane and Finch community. In recalled memories from her childhood, which were filled with contradiction, Reid explained how her vision for her work came into being.

On the one hand, Jane and Finch was a community where Reid had fun and made close friends. But on the other hand, the same spaces she walked through with ease were also (and continue to be) externally framed as ‘bad’ or ‘dangerous’ by the media and others.

Last month, for example, Councilor Giorgio Mammoliti made several anti-Black statements about tearing down social housing, and he even likened those on social assistance – his target being the Jane and Finch community – to “cockroaches” that need to be scattered. Given that Jane and Finch has been ‘mapped’ as a Black space, these kinds of messages help to affirm why exhibits like Reid’s are so important to reframing conceptions of blackness in this city and beyond.

After earning her diploma in Creative Photography from Humber College, Reid began to think about the intersections of fashion, urban landscape, Black identity and the juxtaposition between reality and illusion, which is embedded within her photographs and embodied through her photographic muse Justine — a model Reid met through Model Mayhem, portfolio website for professional models and photographers.

The exhibit is divided into three themed sets. The first captures Justine in the city. It focuses on urban lifestyle through the lens of a Black woman. In the second set, Justine, in a flower dress symbolizing a sense of freedom not usually associated with Black women’s bodies, appears outside yet in poses that evoke an intimacy purposefully absent in the first series of images.

In the third set, Justine is draped in white, sitting in juxtaposition to other white things – flowers, walls. This final motif reflects a progression from finding herself located in a space not of her making to, in the last sequence, defining her identity through a space of her visioning. The intent, Reid says, is to show Black women as multifaceted and to centralize the point of vision as being that of Black women.

Real Love makes you think about the different ways in which Black women have access to, and encounters in, the public spaces of the cityscape and the lesser-seen secluded spaces of nature. When I look at these images, I’m reminded of Carrie Mae Weems, who, in her 1990 work, “The Kitchen Table Series,” used black and white photographs of Black women sitting at tables smoking cigarettes, doing their hair, engaging in romantic moments with lovers, and having nurturing moments with Black children as a way to reflect the duality and complexity of Black womanhood.

Where Weems used a black and white motif through the photographic lens to speak to this duality, Reid uses dress and hair to similarly create a tension between what is ‘real’ and what is illusory. From the cityscape to the flower fields, the images could literally be anywhere, and set at any time.

The fact that Justine, a dark-skinned Black woman, wears her hair in an Afro — a hairstyle that many still associated with Black Power and Black militancy — is also noteworthy.

The Afro first entered public consciousness as a mod fashion statement in the 1950s, especially in New York, because it was not only palatable to the bourgeois artist scene but, in some circles, it was celebrated. However, against the backdrop of the assassination of African American activists, such as Medgar Evers and Malcolm X, and the 1966 rise of Black Panther founders by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in 1966 and other figures like Stokely Carmichael, the Black Power movement gave new symbolic meaning to the hairstyle.

We tend to locate the narrative of Black Power in the United States almost exclusively. But in Canada, Black Power could be seen from coast to coast in the 1960s, for example in David Austin’s work on the Sir George William Affair in “Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex and Security in Sixties Montreal.” As well, the Congress of Black Writers held at McGill University in October, 1968, also announced that a socio-political shift was occurring within Canada’s Black communities.

On October 19-20, in commemoration of Congress’ 50th anniversary, the Congress of Black Writers and Artists 2018: An Argument for Black Studies in Canada will be held at the University of Toronto’s New College. This event speaks to why Black cultural politics still matter. And as it relates to Reid’s work, such events also point to conversations that are happening in the present that are intimately connected to the past.

Importantly, Black Power was not only about political and social change, and the reclaiming of Africa as the literal and symbolic homeland for Black people; it was also a celebration of the natural texture of Black hair (hence the colloquial term “the natural”). The Afro, which stood as the primary hairstyle of the movement’s leaders, became an aesthetic of political change and Black self-love/knowledge.

For the first time in the mid-1960s, dark-skinned women also became beautiful, in some cases, more beautiful than light-skinned women. The darker one’s pigment and the larger one’s Afro, the more authentically ‘Black’ one was thought to be. This sentiment was embedded within the slogan ‘Black is Beautiful,’ which became a badge worn by those in the movement.

Reid’s “Real Love,” then, is in conversation with 1960s Black self-love and self-knowledge. In one set of photos, for example, Justine holds her raised fist in the air in a pose reminiscent of African American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos who, during the medal ceremony in 1968 at the Mexico summer Olympics, raised their Black-fisted gloves in the air as a sign of Black solidarity in what has become known the ‘Black Power Salute.’

While Justine’s fist is also raised, and because she is wearing white, we are asked to attach a different embodied politics to this pose. Viewers are called to think about what this means through the lens of Black womanhood in the present of Toronto in 2018, but also in a fluid space that is not defined by time or place.

Real Love is both a statement and an ongoing conversation.

This article was written with the assistance of Emilie Jabouin, Researcher & PhD candidate, Communication and Culture, Ryerson/York University.

Cheryl Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the School of Creative Industries, Ryerson University. Follow her on Twitter at @DrCherylT.