In recent months, I’ve found myself wondering whether Toronto City Council’s much-touted laneway suites policy, circa 2018, was nothing more than an elaborate bait-and-switch operation.

This is a provocative statement, I realize, but there seems to be mounting evidence that the entire project will be rendered almost moot by the City’s determination to take a letter-of-the-code approach to approvals. In particular, fire safety objections from City officials have percolated to the surface as a growing number of homeowners apply to develop these units, only to be rejected because the City’s interpretation of the Ontario Building Code has all the flexibility of an old wooden hockey stick.

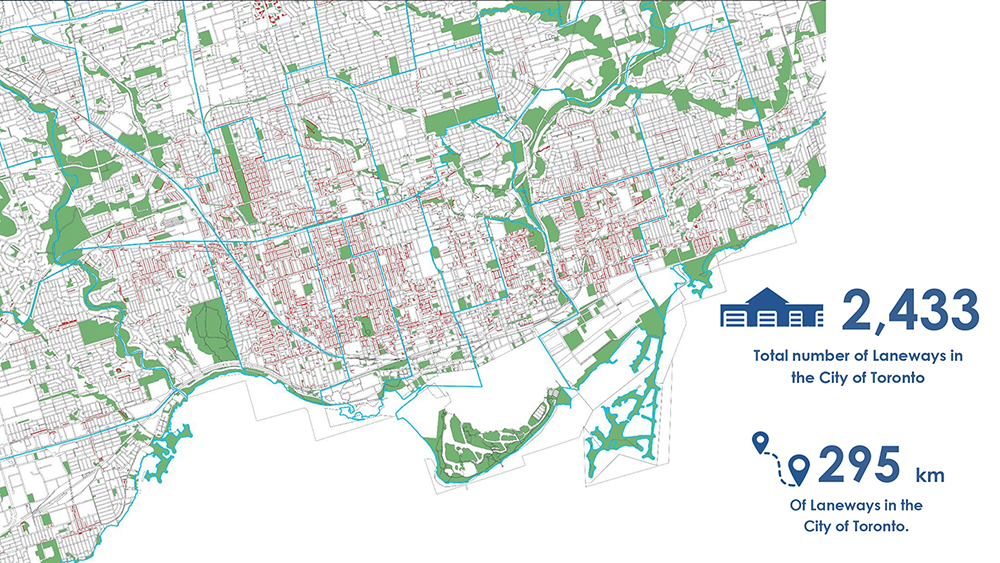

Moreover, all this pushback feels kind of switch-y because when the planning department finally got its institutional head around the scandalous notion of adding laneway suites, it sunily foregrounded metrics that suggested the vastness of this housing resource. For example, the planning presentation to council — entitled “Changing Lanes” and dated May, 2018 — noted that Toronto had 2,433 laneways extending almost 300 kilometres.

The report did caution that not all those locations would be suitable for various reasons, including fire safety issues. But City staff didn’t bother telling residents just how limiting these regulations would be. Did they take 20% of potential locations off the table? Or 50%? Maybe it was 80%? Who knows? But the number isn’t small, I’d be willing to bet.

It’s interesting to note, too, that the presentation didn’t make a single mention of the word “fire.” Firefighter access considerations, one could say, were conspicuous by their absence.

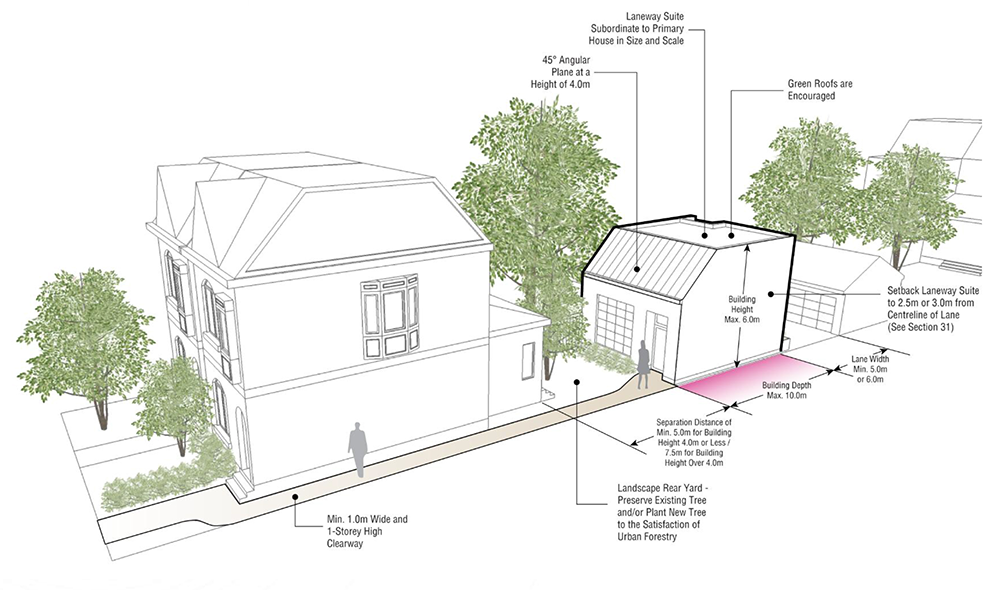

The fire safety and fire access rules are these: to qualify for a laneway suite, the homeowner must have an open one-metre access route down the side of their property, from the street to the backyard. And the suite itself must be no more than 45 metres from the street in terms of travel distance (for firefighters responding to an alarm). Last December, Toronto Building tweaked the former policy in response to concerns from architects seeking approvals for these projects on behalf of clients. Originally, the applicant had to have that one-metre alleyway entirely on one’s own property. Now, it can be a shared path, provided the homeowner seeking approval to build the laneway suite somehow manages to secure an easement agreement with their neighbour to ensure it remains clear forever after.

I can’t say I’ve made an exhaustive study, but when I walk my dog down the laneways in my neighbourhood, which is up the Davenport hill and less dense than some of the downtown areas, I’d say not more than 10% of the properties would qualify. The prospect of quaint Notting Hill-esque warrens, a few images of which snuck into the staff presentations, won’t be coming to my area anytime soon.

In any event, the April, 2018, staff report on the laneway suites noted the fire code requirements, but then added this proviso: “Toronto Building staff has some discretion regarding compliance with the above” (page 23, emphasis added). The document goes on to note that the “Alternate Solution” provision of the OBC, which was activated, for example, to get approval for a tall-timber project at 77 Wade, in the Junction, could be used to develop work-arounds where necessary.

None of that language helped Gal Reuveni, who owns a home with laneway access on Euclid. Last year, he had to appeal his laneway suite application to something called the Building Code Commission (a provincial body not unlike the Local Planning Appeals Tribunal) after being confronted with the wall of no’s from the city.

His lawyers and consultants made the case that the fire access rules imposed by the City go well beyond what’s in the OBC. The Building Code Commission agreed, ruling that the 74 metre distance between the street and his proposed suite was fine, provided he incorporate automatic ceiling sprinklers and sidewalls made with fire retardant materials, as his designers had originally proposed when attempting to get to yes with the City’s building officials.

The BCC provided Reuveni and his consultants with a verbal ruling in December, but the City refused to issue a building permit until the written version was published, which happened in early February.

Interestingly, the BCC decision makes it clear that its ruling should not be seen as a precedent, so if someone else has the temerity to apply for a laneway suite with the same or similar set of conditions, they’ll have to go through the same song and dance, with all the associated costs.

Also interestingly, Toronto Fire — which lurks in the wings of this story — seems completely unwilling to consider, uh, alternate solutions. In an email obtained by Spacing, deputy fire chief Jim Jessop flagged the ruling to Davenport councillor Ana Bailao for her “situational awareness,” as if we’re talking about a burglar prowling through darkened streets.

Jessop also sent an email to chief planner Gregg Lintern and head of Toronto Building Will Johnston a few days after the BCC issued its verbal decision. “This,” he wrote, “is very concerning. I suggest we discuss in the new year…” (Reuveni told me yesterday that he has yet to receive the building permit, and is re-submitting his application.)

Worth noting, too, that the BCC earlier last year (July) nixed another laneway suite application, this time on Palmerston, because the applicant’s side access route was only 0.9 metres wide, not 1.0 metres as specified in the City’s regulations. The difference is roughly equivalent to the span of a small hand, in case you’re keeping score at home. Never mind that the typical to-code front door must only be 76cm to 81cm under the OBC; firefighters manage to squeeze through those all the time.

I don’t want to minimize the importance of fire safety; as a life-and-death issue, it is absolutely important, and should take precedence over all sorts of other requirements or policies. But let’s also acknowledge that perfectly viable solutions exist in other modern, safety-conscious cities.

The problem is that these are the precisely kinds of domains where Toronto’s old and ingrained culture of parochialism, morality policing, and over-regulation still smolders.

Indeed, it’s worth quoting a 2006 staff report that reveals how recently such sentiments circulated in the bureaucracy. “Construction of housing on laneways is not anticipated in the new Toronto Official Plan and it would not be supportable as good planning,” concluded the then acting director of development engineering, before offering up a dismaying list of objections. No. No. And more no.

My question is, why not collaboratively problem-solve instead of either declaring perfectly feasible projects to be unthinkable or forcing homeowners to ante up even more cash to get projects approved — an obstructionist dynamic that will make those laneway suites that much more expensive to rent.

Over the weekend, I spoke to Dean Goodman, a principal at LGA Architects, the firm that designed Reuveni’s project (the one that requires “situational awareness”) and has also been building freehold laneway houses for years. He offered what seems like an outstanding idea. Building code consultants, Goodman says, are the professionals who really understand how to work a design so it fits with the code’s provisions. As importantly, they also know where the code has some give, and can thus find solutions when the jigsaw pieces don’t fit together neatly. As he said, “They’re great at finding alternatives.”

Goodman’s solution – and I hope Lintern, Johnston, and Jessop are listening – is to convene a group of code consultants and task them with developing a set of innovative alternative solutions that satisfy the objectives of the fire safety code. These workarounds would then be readily available to architects and homeowners who are trying to build laneway suites in older neighbourhoods where almost nothing fits neatily into our 21st century regulatory boxes.

“Let’s get a bunch of creative people together,” he urged, “and solve it.”

Yes, let’s — and quickly. After all, at this point, doing nothing is to concede the travesty of a supposedly progressive infill-housing program. Changing lanes, indeed.

photo by Matthew Blackett

9 comments

Good article. The Laneway Suite guidelines are now being set aside on many of our Neighbourhood applicat ions.

Randy

Or maybe we could concentrate on making full size homes accessible and reasonably affordable to the public and drafting policy that encourages this instead of promoting and protecting the few wealthy who can afford them. I guess it’s just easier to allow manor owners to provide the serfs with cottages

Excellent article, and great proposed solution. Rooming houses — the City’s most affordable housing option — share some of the same issues. The fire code’s requirements for rooming houses (defined as any building where more than 3 people share kitchen and/or bathroom and pay rent separately) make it extremely difficult and costly to comply. So good landlords don’t get into the businesses, and bad landlords go under the radar.

I would love to see a group of experts take the approach Dean Goodman recommends to resolve this issue.

So frustrating. In addition the fire code issue could be resolved in another way by allowing secondary units on corner lots, where they would have direct street access. Sadly the report says this isn’t allowed and will be considered at some point in the future, which means probably another 10 year wait.

John, your column assumes that laneway housing is a social good. I think its a social bad.

Take your diagram of the laneway house, which was presented to City Council as the typical scenario. It’s hardly typical: most laneways have more shallow backwards and plenty of T intersections. Some laneway houses ——which don’t require any notice to neighbours or a trip to the Committee of Adjustment—— will be peering into the living rooms of homes next to them, or across the perpendicular T intersection.

Second, imagine the diagram turned 180 degrees to the viewpoint of the neighbour across the laneway. It’s like facing the Hollywood Bowl.

On Yarmouth Gardens we recently discovered (by word of mouth, no notice) that four homeowners across the T intersection on Palmerston were thinking about a row-housing four-plex only a few feet from our backyard windows. They were being egged on a by one of the many new laneway contractors who see a business opportunity. We can kiss our privacy and peace and quiet good bye.

If urban density is a good thing, there are many less invasive ways to go about it. Homeowners might be encouraged to build up or down, not sideways towards their neighbours. We might do something about the height restrictions on main thoroughfares.

Very disappointed in our City Councillors. You would have hoped that something like this would have been better publicized when it came to Council, I am sure I would have had some company in speaking against it.

This is why I argue that the regulations that need to be removed are at the municipal level not the provincial or federal level. Municipalities do not apply their by-laws clearly or evenly (look at that TTC 2 hour transfer fiasco as another example). There is too much subjectivity, lack of transparency and regulation getting in the way of people doing their thing or businesses doing their thing. This is where regulation reduction needs to be focused.

I’m with Howard and Greg on this one. The people mainly pushing for laneway houses are investors and contractors and landlords. Without tight regulation, we’ll have crummy shacks shoehorned into every nook and cranny while the landlords run away with the money. Meanwhile, the rest of us will have to deal with over-cramped, crapified neghbourhoods and illegal hotels in our laneways. This is a bad solution to a non-existent problem.

There are lots of places and ways to build and densify that don’t create a 21st century version of The Ward.

JW ands Howard — Your attitude towards laneway housing is beyond ridiculous. “A public bad”?!!! “crummy shacks?” “people mainly pushing for laneway houses are investors and contractors”.

Nothing is further from the truth. Its people who want more space. Its people who have a basement apartment but can now rent something better. Its people who can see that adding gentle density to a neighbourhood IS A PUBLIC GOOD.

Having taken part in numerous meetings and workshops, I cannot tell you how wrong you are.

Lulu – come back and update us on your opinion after your postage-stamp of a backyard is walled in on both sides by cockroach-infested ghost hotels that your REIT neighbours refuse to fix because they’re in Hong Kong or London or Panama and they don’t give a hoot about the local working families that were chased out of the neighbourhood by the flood of laundered money.

This is a cash-grab, plain and simple. It’s a bad solution to the wrong problem, and will permanently scar old neighbourhoods. The city is wise to approach this carefully. The “experts” at your meetings are wrong.