This is an excerpt from Modest Hopes: Homes and Stories of Toronto’s Workers from the 1820s to the 1920s — by Don Loucks and Leslie Valpy — which celebrates Toronto’s built heritage of row houses, semis, and cottages and the people who lived in them.

ANNE O’ROURKE (circa 1820–1891)

ANNE O’ROURKE (circa 1820–1891)

34 Bright Street, 38 St. Paul Street

The story of Anne O’Rourke (née Delaney) of 34 Bright Street and 38 St. Paul Street in Corktown is drawn from correspondence with her great-great-granddaughter Vickie Wybo-Yuhase as well as from additional research.

Anne Delaney was born in Ireland around 1820. In her late teens, she married Martin O’Rourke (born 1806) of Ballyfin, Mountrath, Laois, Ireland, who was almost 15 years older than she was. Correspondence with the O’Rourke family suggests that Anne and Martin came to Canada, circa 1847, in connection with the Irish Potato Famine. They would have seven children in Toronto.

By 1848, the O’Rourkes were in Toronto, though their first address has proven difficult to track down. It is not until 1856 that they appear in the Toronto directories, living in Toronto’s east end. On July 29, 1848, Martin and Anne gave birth to Mary in Toronto, the first of Anne’s children to be born in Canada. Two years later, on August 1, 1850, the couple had Bridget. Sadly, this baby died on March 26, 1851, less than a year old.

The O’Rourke family continued to grow. In 1852, Anne gave birth to their third child in Toronto, also named Anne, soon followed by James on March 30, 1854. In less than a decade after their arrival in Toronto, the O’Rourkes were now a family of five.

In 1856, the O’Rourkes finally show up in Toronto directories. Martin “Rourke” is listed on North Park (Shuter) Street between Pine (Sackville) and Sumach Streets. Like many of his neighbours, Martin worked as a labourer. That same year, their daughter Catherine was born. Godparents listed on their children’s baptismal records are fellow Irish immigrants as well as neighbours on North Park Street (such as Joseph Costigan and Patrick Coulehan), suggesting the strength of their new community and its deep roots in their homeland. Costigan and Coulehan are recorded on North Park Street in 1850, hinting that the O’Rourkes could also have lived there as early as 1850. As well as being godfather to their second-youngest son, Joseph Costigan became an important neighbour to Anne in the years to come.

While living on North Park Street, the O’Rourke family expanded again. In 1858, Martin Jr. was born (neighbour Joseph Costigan is named as godfather) and their youngest and final child, John, followed in 1861. Sadly, on February 20, 1861, Martin Sr. died and Anne was left a widow with six children.

Tiny, crooked Bright Street first appears on a Toronto map in 1862. That year, two small one-storey side-by-side cottages were the first on the street. Joseph Costigan, Anne’s former neighbour on North Park Street, occupied the first cottage, while newly widowed Anne lived in the two-bedroom cottage directly beside him, with her six children. This Bright Street cottage represented a new chapter for Anne at age 42: her first house alone, her own Modest Hope.

Anne found work as a dairywoman or milkwoman. It is likely that she did so at the Gooderham & Worts dairy located just blocks from her Bright Street cottage. William Gooderham’s business had begun as a flour mill; he then added a distillery to his operation in 1837 after a year of surplus grain harvests, initiating the basis for the production of his first whiskey. As manufacturing expanded, so did the company’s wastes, which Gooderham initially sold to farmers for feed. He then recognized the revenue that could be made by keeping his own cows and pigs, so just as the distillery had grown out of the mill, a livestock operation sprouted from the spirits business.

By 1841, Gooderham had established a large dairy on a nine-acre site between Trinity and Cherry Streets across from his mill. Both the dairy and the distillery employed many residents in Corktown. “A business tycoon with a social conscience,” Gooderham “also financed the building of small, affordable cottages” on Corktown streets such as Trinity and Sackville “for many of his workers and the city’s growing working class.” Gooderham also saw the benefit of having his employees live close to work.

In late 1867, Anne and Joseph, Bright Street’s sole occupants, were joined by another neighbour, Edwin Apted, who moved into a cottage across the street. By 1871, Anne was still sharing the compact onestorey, two-bedroom cottage with her six children, which likely included her recently widowed eldest daughter, Mary, and Mary’s two children. Space and money was tight. Anne continued to work as a dairywoman, her daughters, Anne and Mary, found jobs as servants, and her son James

became a tinsmith.

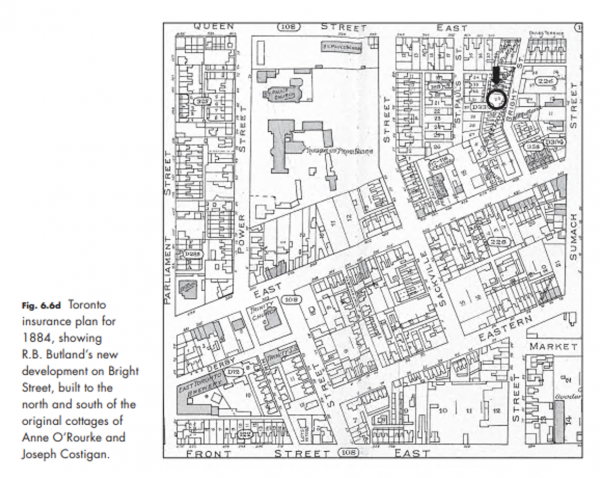

Around 1872, philanthropist and music dealer Richard Brooking Butland purchased numerous lots in Corktown as well as several pieces of land to the north and south of Joseph’s and Anne’s cottages, with the vision of creating a newer and better Bright Street. He demolished many of the existing cottages that had been built on the street and began construction of Victorian two-storied, brick-fronted terraced homes. But Anne and Joseph refused to sell their cottages. Butland’s dream of a newly terraced Bright Street was derailed by their holding out, which remained stuck in the middle of the streetscape on the west side. Instead, he developed terraced rowhouses to the north and south of Anne’s and Joseph’s cottages. In 1872, he first constructed five rough-cast cottages to the south of Joseph and Anne, selling them for $500 each.

By 1875, Butland had erected terraced rowhouses to the north of Joseph’s and Anne’s cottages, as well. Housing on Bright Street mushroomed in the 1870s, and by the early 20th century, similar rowhouses also lined the east side of the street. Joseph’s cottage became 32 Bright while Anne’s became 34 Bright.

Compact and densely populated, Bright Street was at the centre of impoverished Corktown, a predominately Irish working-class enclave. Many residents lived in houses originally built for single families, but poverty often forced multiple families into one home. Bright Street appears not to have had the best reputation, either. Mentions of it in the Globe and Toronto Star newspaper archives feature reports of petty crime, unfortunate accidents, and personal tragedies. Mary Metcalf was arrested for stripping a Bright Street clothesline in 1879; John Evoy, at number 28, was arrested in 1883 “on a charge of drunkenness and larceny of various articles to procure liquor”; Peter Currant, at number 23, was arrested in 1896 for assaulting two “Chinamen.” The most troubling mention of the street came in 1908 when Matthew and Alma Mathieson were found huddled for warmth in an empty house on Bright Street. The Mathiesons had been homeless since Matthew had lost his job at Conboy Carriage Company. They had not eaten in three days.

There were also mentions of dog-related crimes. In 1875, a fight over a stolen dog led to murder next door to Joseph Costigan’s house. And in 1881, eight-year-old John Burns was badly bitten by a bulldog, its owner charged for not having a licence. That owner was Anne O’Rourke, now living a block away on St. Paul Street.

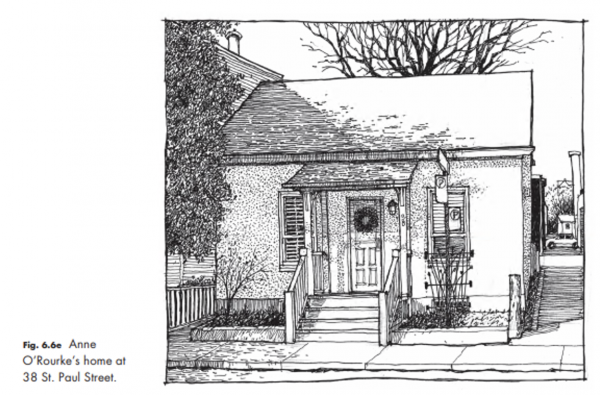

Anne had moved off Bright Street in 1874 to 38, formerly 10, St. Paul Street, one block away. The two Bright Street cottages remained side by side, surrounded by the curved terraced rowhouses that followed the arc of the street. Joseph Costigan remained at 32 Bright until his death in 1879, and his wife, Julia, and their son continued to live there for many years after he died. Just up the street from Julia at number 42 Bright lived the noted Henry Box Brown, a Virginia slave who escaped to freedom at the age of 33 by having himself mailed in a wooden crate to freedom in Philadelphia in 1849. Upon his delivery to liberty, he first moved from the United States to England where he toured as a magician, entertainer, and abolitionist speaker before immigrating to Toronto. He lived at 42 Bright from 1890 to 1893 and died in Toronto in 1897.

The cottage at 34 Bright Street, once the home of Anne O’Rourke, remained side by side with Julia Costigan’s for a few more years. However, by 1910, it was finally sold to a developer and demolished. In its place, 34–36 Bright went up, blending in with its terraced neighbours to the north. The cottage at 32 Bright became the only remaining one of its kind on the west side and eventually the sole one on the whole street.

Anne’s time on St. Paul Street began in 1874 when she moved to a new Modest Hope, number 38, formerly 10. While the St. Paul cottage was still two bedrooms, it was slightly larger than her Bright Street home. She continued to work as a dairywoman, while the children who still lived with her helped pay the bills. Catherine, now 23, was a seamstress, while sons Martin, 21, and John, 19, followed in their father’s footsteps and worked as labourers, John at the dairy with his mother, Martin eventually becoming a teamster for P. Burns & Company.

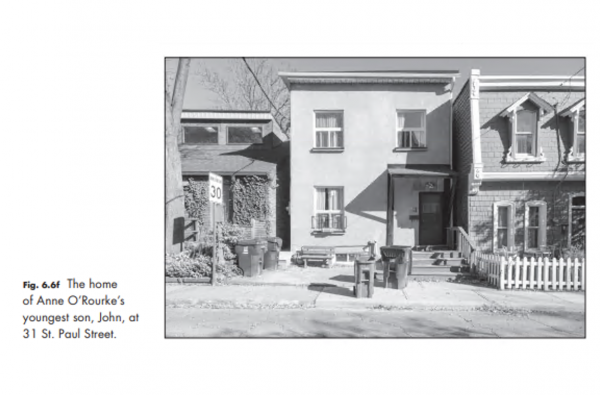

In 1885, Anne’s youngest son, John, married Catherine Prior, and they moved across the street to 31 St. Paul, formerly number 13, where they started a family in their own Modest Hope. Anne continued to live at 38 St. Paul with her son Martin until 1890. The next year, Martin was listed at 93 Parliament Street, while Anne disappeared from the city’s directories. It has been difficult to determine if this was the year she died.

Anne’s son Martin moved back to St. Paul Street in 1892 and into number 26, now demolished, but he lived there for only a year, dying of Bright’s disease on October 11, 1893, age 34. Her son John continued to own properties on St. Paul Street, eventually purchasing 31 and 31½, which he turned into rental units. He also appeared to still own his mother’s former home at 38 St. Paul, since he is listed at that address for a few years before moving to 73 Frizzell Street near Pape and Danforth Avenues. Upon his death in 1917, John had amassed a modest estate, a far cry from his family’s humble roots as Irish Famine immigrants to Toronto.

top photo by Vik Pahwa

Excerpted from Modest Hopes: Homes and Stories of Toronto’s Workers from the 1820s to the 1920s by Don Loucks and Leslie Valpy ©2021. Published by Dundurn Press Limited.