It’s getting to be that time of year – queer or straight, people will be busting out the rainbow garb and glitter. Toronto hotels and restaurants will once again be overflowing with post-pandemic Pride tourists, and companies will flaunt their allyship with sponsored window displays, floats, and advertising.

It’s been a good fifty years since Canada’s first Pride events. They were mostly small-scale social gatherings or political protests where the gay community (as it was then called) began to assert and demand its rights. And then the 1981 Toronto bathhouse raids happened, a watershed moment less famous than the Stonewall riots in New York, but critically important to our understanding of Canadian and queer history.

Retired teacher Amy Gottlieb had moved to Canada from New York in 1972 to attend Trent University. As a teenager, she had known she was attracted to women, and never really worried about it. Her student years cemented her sense of herself as a feminist and a lesbian.

On a Jane’s Walk through The Village many years ago now, she told me about the origins of her queer activism. “My first involvement was in response to the notions of sin and sickness being spread by Anita Bryant.” The American actress came to Toronto on a speaking tour in the late 1970s. Bryant was well-known as a spokesperson for both Florida orange juice and the anti-gay movement. Bryant had a receptive audience, especially when she trotted out the argument that gay adults were grooming the young. “To freshen their ranks,” said Bryant, “they must recruit the youth of America.” One of her more egregious quotes was: “If gays are granted rights, next we’ll have to give rights to prostitutes and to people who sleep with St. Bernards and to nail biters.”

At the time, there was a vocal group of parents in Toronto who wanted to prevent queer teachers from being hired, and to keep any and all education about homosexuality out of the classroom. They also stoked the utterly fact-free fear that having role-models and information would turn kids gay. Gottlieb describes it as a kind of “sex panic.” She would call the situation for openly queer people forty years ago extremely dangerous. There was no job protection, and same-sex parents could have their children removed. “The love and sex that we experienced were enthralling. Who were we hurting? We just wanted to live and love freely and be happy,” she says, “We were in love with being who we were.”

On February 5, 1981, Toronto police swooped in and arrested nearly 300 men for being “in a common bawdy house.” “Operation Soap” was the large-scale raid on four bathhouses, carefully planned and orchestrated. To be clear, there was plenty of sex happening in these places, but no paid sex work or criminal activity. The police brutalized and humiliated those they arrested. The Toronto Sun called it “nonsense” to conclude that “homosexuals are being picked on,” while the Globe and Mail pointed out the hypocrisy of the situation: “Even in the days when there were raids on heterosexual bawdy houses, few charges were laid against found-ins. The impression upon the public cannot fail to be that the police are discriminating against homosexuals.”

As soon as word spread, thousands of infuriated people took to the streets to protest. Marches continued throughout the winter of 1981. The community quickly came together to mount a spring march/parade that would be bigger and brasher than any of the previous decades’ picnics or rallies. Three existing activist groups joined forces to form the first officially incorporated Lesbian and Gay Pride Day Committee. The end of June was chosen to coincide with the anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

Toronto’s first formal Pride event was part celebration, part protest. About a thousand people gathered at Grange Park behind the Art Gallery of Ontario for a picnic with speakers and entertainment. Gottlieb says the day was about visibility and pride, but people were also angry. They marched along Queen Street, up Yonge and across Dundas. In front of 52 Division of Toronto Police Services, the protesters made a thundering wall of sound. Gottlieb remembers it as the moment the community truly found its voice. “We stood outside and yelled ‘Fuck you 52!’ for five solid minutes. It was a dream. So many people came together to say ‘we are entitled to live our lives’.”

Of course, much has changed since 1981, which happens to be the same year that Gottlieb met the woman who remains her partner today. During her time as a teacher, Gottlieb felt that Pride was important primarily as an opportunity to support LGBTQ students.

“Love is love“ has been the feel-good tagline of the current millennium. When Toronto hosted World Pride in 2014, it brought out all the VIPs. The City of Toronto threw a mass wedding at Casa Loma for more than a hundred same-sex couples as part of the festivities. Gottlieb has some opinions about who is served by this kind of display. But if you had described the events of June 2014 to her thirty years earlier, she says, “I would have thought that was a pipe dream.”

And now the pendulum is swinging back into dangerous territory, as many feel empowered to target the queer community once again. A tactic as old as humanity is being employed to try to erase our existence: the banning of books. Voices from the fringes are being amplified. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis successfully passed his “don’t say gay“ bill just last year, forbidding instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity from kindergarten through grade three. Closer to home, protesters successfully disrupted a drag storytime event at the Fort York branch of the Toronto Public Library earlier this spring.

It feels rather like the 80s are back, minus the shoulder pads and vertical hair. As with every movement for equality, there is pushback from those who somehow feel that the rights of others must come at a cost to their own. It took immense courage for Amy Gottlieb and her cohort to be out and active in the fight for equal rights forty odd years ago. By contrast, it made no splash whatsoever when I started dating women in the late 1990s. At this polarized moment in history, I can only hope that my grandchildren will look back with shock and disbelief at the current attacks on queerness, and be inspired by the huge strides made by their LGBTQ forebears.

Mary Fairhurst Breen is the author of a book for middle grade readers coming out this fall from Second Story Press, Pride and Persistence: Stories of Queer Activism.

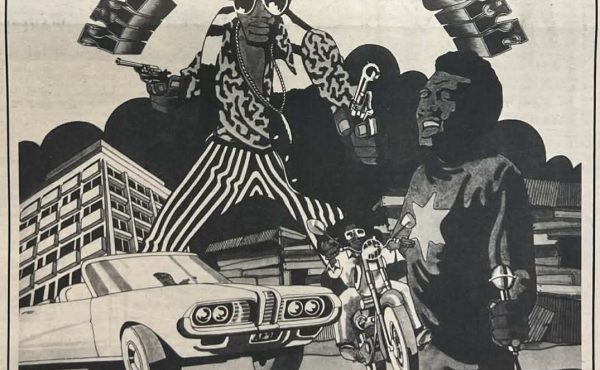

Photo courtesy of Amy Gottlieb.

2 comments

I wish everyone who finds themselves part of the 2SLGBTQ community to have peace of mind and heart, freedom from fear, and hopefully joy as well.

Thank you, Amy, for your years of energetic activism! Wishing you a very happy Pride!